Among the many theories for how the concept of race emerged, from capitalism and class struggle to plantation slavery, is a common trait — they all begin in the modern era. Use of the word “race” to denote something other than a brisk run, after all, doesn’t occur until the 16th century.

Attempts to apply race to pre-modernity is considered by some scholars to be anachronistic, and proponents are slapped with the rather academic burn of “presentism” (viewing past events through a lens of present-day values). Discrimination as it occurred in the Middle Ages is thus not racism, but instead termed xenophobia or ethnocentrism.

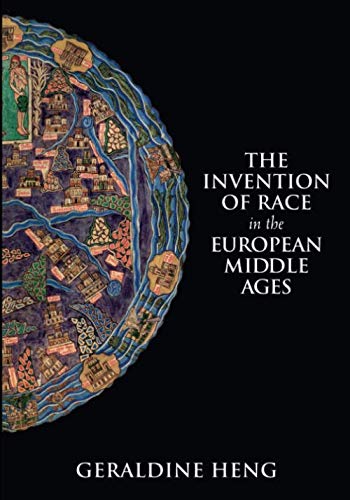

In her new book, The Invention of Race in the European Middle Ages, which was awarded the Hamilton Book Award grand prize and the Medieval Institute’s Otto Gründler prize, Geraldine Heng uses a variety of literary, cultural and historical sources to argue against this position, stating that race did indeed exist in medieval Europe even if the language of the time had yet to capture the phenomenon.

“If we set aside everything we have conventionally been told about race and just look at the incidents, at the laws, at the atrocities and ask ‘If this had happened today would we call it race?’” says Heng, a professor of English and Comparative Literature at The University of Texas at Austin. “And I think we would.”

Defining Race

Because science (or more often pseudoscience) was used to justify racism in modernity, we tend to think of race today in terms of physical traits, most notably skin color. But race, as Heng defines it, is a mechanism for sorting humans into categories by selectively essentializing certain differences in order to unevenly distribute power.

Such differences can be cultural as well as biological and are seen as fundamental to individuals within racialized groups, something that cannot be escaped by behavioral modification alone. A Jew who converts to Christianity in medieval Europe does not cease to be a Jew, they merely become a convert. The stigma of race can persist for generations, as in the case of Anacletus II, who was disqualified as a candidate for the papacy in the 12th century over rumors that he was the descendant of a Jewish convert (undeterred, he served as Antipope until his death in 1138).

Despite being intimately tied to one’s identity, race is not static. The boundaries of race are redrawn as societies change. Irish immigrants, for instance, were once racialized in the U.S., but today they’re lumped in with the rest of white people.

The immediate goals behind race making are also varied. Creating a racial minority can unify a disparate population against a common other. It can justify the invasion of a foreign nation, the seizure of property and the denial of rights to certain individuals. All of these are motivators that existed long before the Age of Enlightenment.

While researching her first book, Empire of Magic, which traces the emergence of King Arthur legend in literature through the history of the Crusades, Heng encountered many instances of what appeared to be race and racism labeled with era-appropriate euphemisms.

“The refusal of race destigmatizes the impacts and consequences of certain laws, acts, practices, and institutions in the medieval period so that we cannot name them for what they are and makes it impossible to bear adequate witness to the full meaning of the manifestations and phenomena they installed.”

Geraldine Heng

“The refusal of race destigmatizes the impacts and consequences of certain laws, acts, practices, and institutions in the medieval period so that we cannot name them for what they are and makes it impossible to bear adequate witness to the full meaning of the manifestations and phenomena they installed,” Heng writes in the new book.

To classify such discrimination as racial is not, in Heng’s view, an imposition of modern values on earlier times. It is simply the application of language not previously available to more accurately describe events that easily meet the criteria of race.

Religion as Race

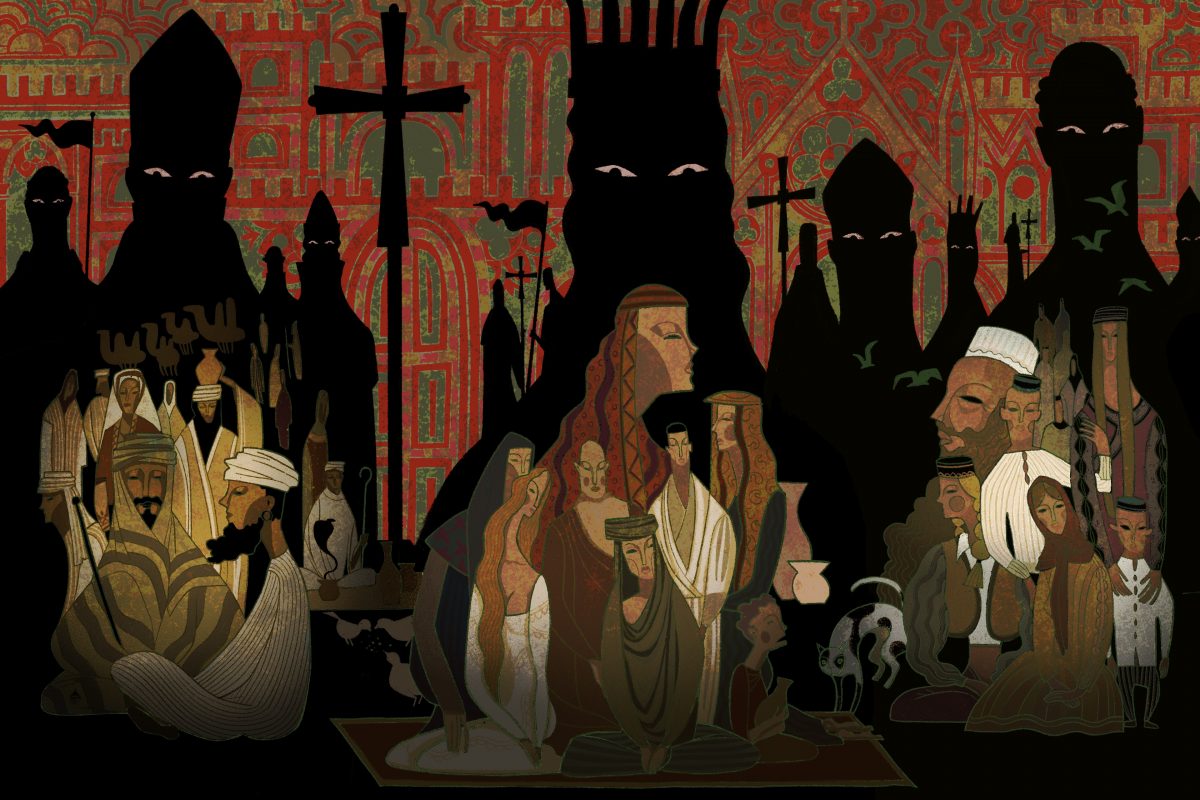

Before the scientific revolution focused race on superficial biological differences, religion was the organizing principle of European society. The church was thus the authority on human variation, and non-Christian groups, regardless of their diversity were sorted by their faiths. Heng explores medieval conceptions of two such groups — Jews and Muslims, the latter a foreign threat encountered in battle, the former an alien race living side by side with European Christians.

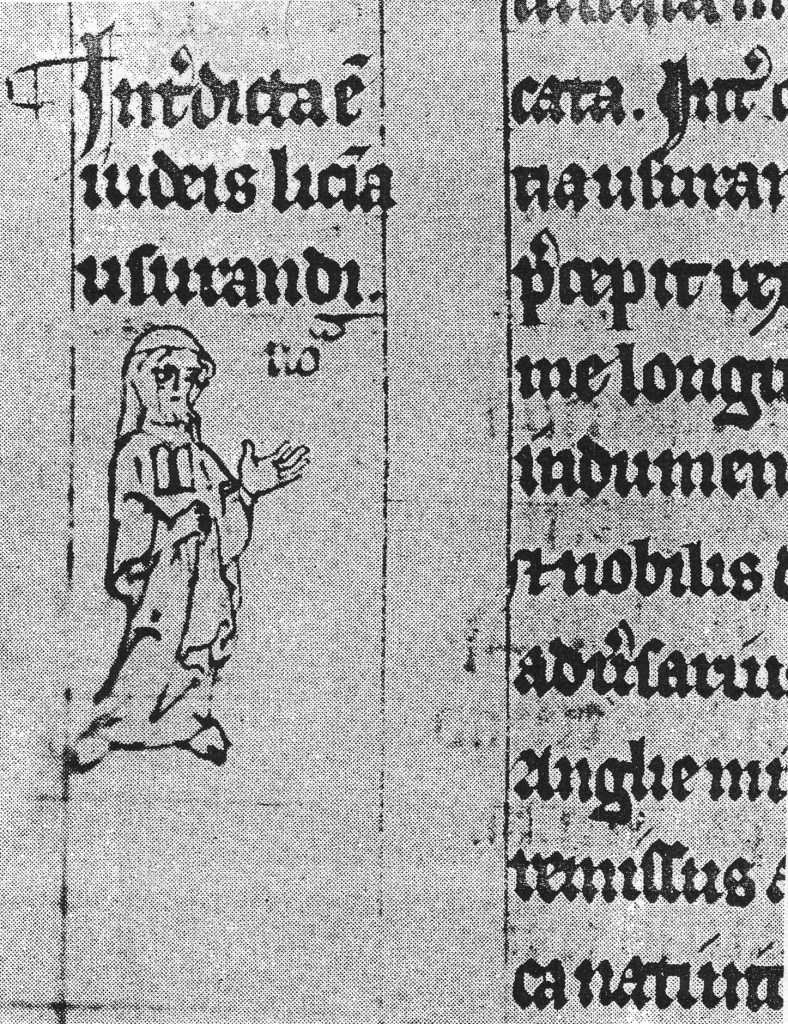

In her case study of Jews in medieval England, Heng catalogues a history of maligning and mistreatment culminating in the group’s formal expulsion from the country. The tactics will sound familiar to any who has studied 20th century European history. Jews were depicted as fundamentally distinct from Christians by virtue of mostly imagined characteristics — specific facial features, a foul stench, even horns. Despite such seemingly easy to spot hallmarks, they were compelled by law to wear badges demarcating their status as Jews.

Additional legislation selectively taxed Jews and corralled them into neighborhoods segregated from their Christian counterparts. Acts of mob violence against Jews were not uncommon. Various libels were fabricated to legitimize such treatment, most famously that Jews used the blood of Christian children in their religious rituals. Finally, in 1290, King Edward I’s Edict of Expulsion forced the group, estimated to be fewer than 2,000 individuals, to leave England.

The departure of its Jewish population didn’t stop England from using them as a convenient symbolic enemy. “In the medieval period, Jews functioned as the benchmark by which racial others were defined, measured, scaled, and assessed,” writes Heng. Any group could be tucked into the hierarchy by being deemed better or worse than Jews.

Cambridge University Press, March 2020

By Geraldine Heng, professor, Department of English

The racializing of Muslims to bolster support for the Crusades required grouping geographically and ethnically diverse peoples into a singular other — the “Saracen.” The term Saracen, originally applied to Arabs, was coined by Saint Jerome, who falsely asserted that Arabs themselves had created the moniker in order to claim ancestry with Abraham’s legitimate wife Sarah (rather than the slave woman from whom Jerome believes they descended). During the rapid spread of Islam, the word came to denote not just Arabs but any Muslim.

Refusing to acknowledge the heterogeneity of one’s enemy is a way of dehumanizing them on the battlefield. Saint Bernard of Clairvaux argued that the killing of a Muslim was not homicide but “malacide” — the killing of the embodiment of evil. Yet narratives of the Crusades also allowed for the possibility of redemption through religion, and medieval literature is sprinkled with stories of European princesses converting Saracen husbands to Christianity. The historical reality is somewhat a reverse, with European boys sold as slaves to Muslim armies (by other Europeans, no less) converting to Islam and becoming warriors and rulers in their adoptive lands.

An Era of Increased Encounter

The Crusades gave medieval Christian Europe its first significant exposure to the East and in some ways consolidated its cultural identity. Prior to this time, whiteness was neither a desirable trait nor an integral part of European identity.

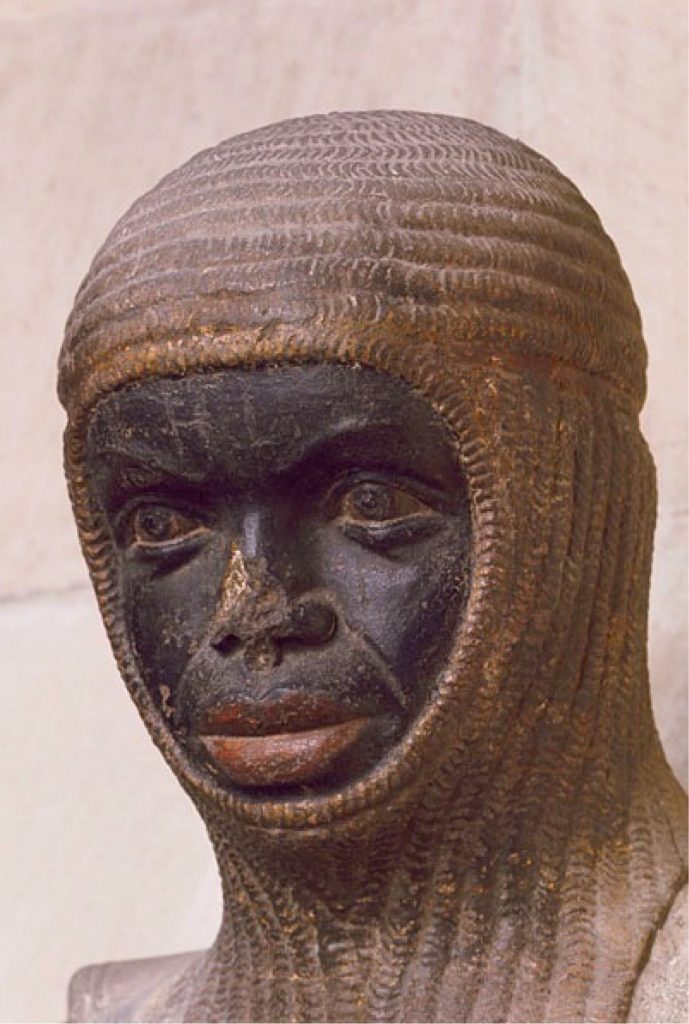

Northern and Western Europeans living in relative isolation had little need to contemplate their own skin color, but as their encounters with darker skinned people increased, pale skin came to be associated with virtue rather than sickliness. This can be observed through a shift in visual depictions of European skin over the course of the 13th century. Realistically rendered pinkish-brown tones gradually brighten until the limbs of saints are as colorless as the whites of their eyes.

The concept of blackness, conversely, arose as an abstraction within Christian theology, lacking the benefit of contact with non-white individuals to guide it. The results are predictably dramatic. Black is the color of sin, the color of the demonic, the color of evil. Yet in an age before science-sponsored racism, the physical detail of skin color was not as important as cultural factors like Christianity and chivalry, and the noble deeds of dark-skinned heroes could serve as a powerful metaphor for salvation.

“Now that you have these two binaries, black and white, you have this witty play with color,” explains Heng.

If black was the color of sin, then the ability of a dark-skinned African like Saint Maurice to overcome the burden of blackness and rise to sainthood surely meant that ordinary white sinners could repent their way back to God’s good graces.

In general, concepts of race formed at greater distances from their subjects contain more fantasy. Christian Europeans living far from any Muslims tended to conceive of Islam as an exotic polytheism, whereas those in contact zones couldn’t help but acknowledge Islam’s overlap with Christianity, even if they opted to view the religion as a corrupted version of their own.

“Knowledge does not necessarily preclude race making,” says Heng. “But it can result in some degree of accommodation, in some degree of realism and in more adaptive strategies of race making suitable to local context.”

Distance can be temporal as well as spatial. The image of medieval Europe held by today’s white nationalists is one of a uniformly white ancestral homeland, which conveniently omits the considerable mixing of genepools that occurred in societies rife with sexual abuse of domestic slaves.

The latter half of The Invention of Race in the European Middle Ages describes European encounters with people of even more distant origins with religions and cultures as unfamiliar as the continent had ever seen. Through the Vinland Sagas, we learn of aspiring colonizers from Greenland and Iceland and their failed attempts to conquer land inhabited by Native Americans. Through travel narratives and account of explorers like Marco Polo, we learn of the vast Mongolian Empire, which Europeans both feared and envied. And, finally, we meet the Romani, one of the most under-researched groups of the Middle Ages.

Romani Resilience

The Romani migrated from Northwest India during the 11th century, traveling through the Middle East before making their way to Europe. An ethic group without a nation, they remained nomadic and, like European Jews, were forcibly expelled from several nations.

The Romani also shared with Jews false accusations of crimes against Christianity, including claims that their ancestors had forged the nails used to crucify Jesus (this despite the seemingly airtight alibi of not being anywhere near the Crucifixion for another thousand years). Stereotypes that they were thieves and sorcerers were quick to emerge and persisted well into the modern era (recall the fortune teller with crystal ball imagery from the carnivals of your childhood). Ultimately, hundreds of thousands of Romani found themselves enslaved in what is now Romania, a legal status of their race which they would not escape until the 19th century.

Despite the persecution, continued uprooting and forced assimilations they endured, as well as the diversity within their diaspora, the Romani fought to preserve a shared cultural identity. Here we see a distinction between a racial identity imposed by external forces and one constructed within a community. While the former is a tool of exclusion and oppression, the latter can unite a group in times of adversity.

Having taught several courses on race at UT Austin, Heng has observed firsthand how learning about the persistence of racism in human history can be discouraging to students. But she tries to mitigate the despair by highlighting instances of appreciation rather than condemnation of foreign cultures.

“We need the young to be optimistic enough to keep working toward social justice,” she says.

The story of race in medieval Europe can be a difficult one to read, and Heng strategically closes her book with the resilience of the Romani to leave us with a sense of hope.

“We see that race can be made from the outside, against a people,” she writes in the book’s conclusion. “Or from the inside, by a people who in the end could not, despite custom and law and the abjection of slavery, be erased and destroyed.”