Last year, Ukraine took the entertainer-turned-politician game to the next level by choosing Volodymyr Zelensky, previously best known for his television portrayal of a man who inadvertently becomes president of Ukraine, to be their actual president. A small group of UT Austin students and faculty members followed the election closely as they prepared for a summer research project in Ukraine on youth political engagement and social media.

“I am amazed by these students.” says Mary Neuburger. “In all of my 20 years at UT I have never seen such motivated, passionate undergraduate students. They were running this with me, it really was collaborative.”

Neuburger and Oksana Lutsyshyna, the program leads, worked closely with the students to refine the topic and organize the trip to Ukraine — its history and current political climate make it a fascinating place to study the influence of social media on politics. The project was coordinated through the Center for Russian, East European and Eurasian Studies (CREEES) and was a finalist for the university’s President’s Award for Global Learning.

Understanding a Turbulent Nation

Throughout the spring 2019 semester, the group gathered survey data and spoke via Skype with college students in six Ukrainian cities, asking questions about the election campaigns and results, the state of democracy in Ukraine, and the role of social media in politics. Over the summer, they traveled to four of the six cities to conduct follow up in-person focus groups, as well as having more informal discussions with people involved in local political and social activism. They followed several Ukrainian social media influencers and, with the help of UT political science research fellow Kiril Avramov, analyzed data gathered from these sources.

Their research findings, which will be published in the journal Social Media and Society, revealed an atmosphere of cynicism. And coding of the social media influencer data showed, not surprisingly, that most of what was written about the candidates was negative. But it was also infused with dark humor. This use of humor as an antidote to chronic disappointment may be another reason why a comedian was the candidate who came out ahead.

Since gaining its independence after the fall of the Soviet Union in 1991, Ukraine has been through two revolutions and six presidents. Russia’s annexation of Crimea in 2014 in the wake of the Euromaidan revolution further destabilized the situation, as did providing military support to pro-Russia insurgencies in Ukraine’s eastern Donbass region, which remains a warzone with heavy civilian casualties.

Ukraine’s foray into democracy has been hindered by widespread corruption and a wearying cycle of hopes raised and then dashed with each change in leadership. All this has left the Ukrainian people understandably a bit wary of both establishment politicians and traditional news media.

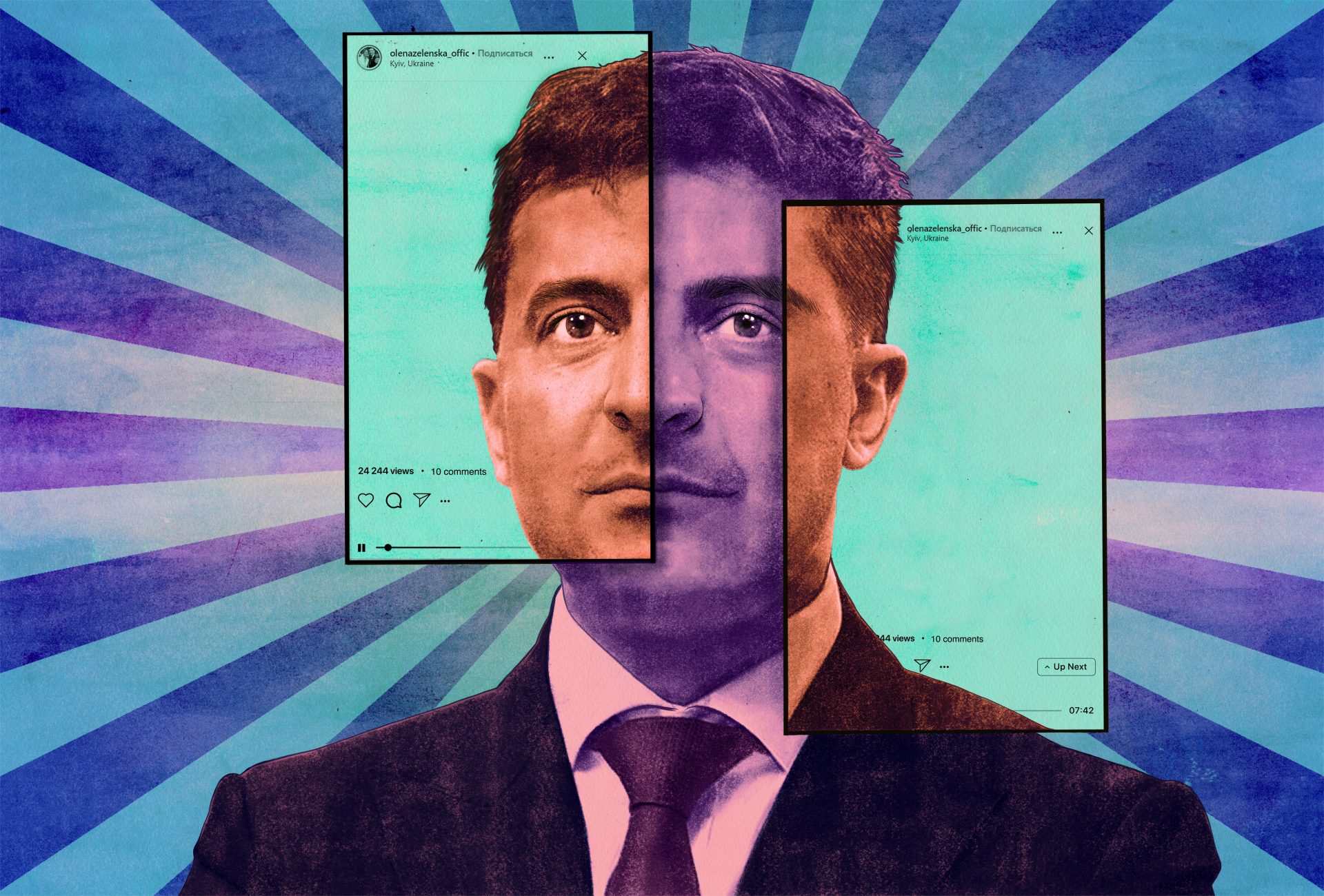

Enter Zelensky, a comedian and actor whose popular television show Servant of the People tells the tale of a humble teacher who somewhat accidentally wins Ukraine’s presidential election after a video of him ranting against political corruption goes viral. Zelensky’s real life campaign took the country by surprise when he entered the race just a few months ahead of the April election, well after Neuburger and company had outlined their project goals.

“He came out of nowhere,” says Neuburger, the director of CREEES and chair of Slavic and Eurasian Studies. “Literally out of nowhere.”

The Selfie Savvy Candidate

In keeping with the life-imitates-art theme, Zelensky ran under a party named after his show and spun his political inexperience as an asset, promising that he was the only candidate not beholden to corrupt financial interests. And while his success bears some similarity to a certain American TV star who offered promises of swamp draining over political expertise, there are several crucial differences. For one thing, Zelensky actually did win by a landslide, receiving 73% of the vote in the runoff election. (Ukraine has a multiparty system, so if no one wins the majority of votes in the first election, the top two candidate square off in a second round). Additionally, he ran on a platform of unity rather than division, in a country where division is an easy route to take. But perhaps most importantly, he used social media in a novel way that resonated with young voters.

Zelensky’s approach to social media was more informal than that of the other candidates and he made smart use of Instagram, one of the more popular platforms among youth, where he posted goofy selfies portraying himself as friendly and approachable. The benefits of this strategy were reflected in the survey data the UT Austin group collected during the spring, in which the majority of Ukrainian students indicated Zelensky as the candidate who best used social media.

“What I was interested in as an historian is at what point can we say that social media has created a completely new political ecosystem?” says Neuburger, recalling the days before the Internet was sufficiently widespread to exert any influence on politics. “It’s not just a matter of degree, we’re operating in a completely different world and we don’t fully understand what that means yet.”

Different Kinds of Activism

Overall, the researchers found social media to have a strong effect on political engagement among Ukrainian youth. Distrustful of Ukraine’s oligarch-owned media outlets, students there relied heavily on social media for information. They also viewed social media engagement (posting, liking and sharing) as a form of political participation.

Another aspect of Ukrainian youth’s disillusionment with politics was their unwillingness to describe themselves as “politically active” despite what might look to Americans as passionate involvement in political causes. Maya Patel, one of the UT Austin students involved in the project, explains this seeming contradiction.

“We realized that they consider social activism to be very different from political activism,” says Patel. “A lot of these people see their government and their political system as so broken and so corrupt, so they see social activism as a way to make change without using this very broken system and as a way that they can fix the very broken system.”

So, while Ukrainian youth have little interest in doing phone banking for political candidates, they are likely to volunteer with NGOs and other organizations to improve their communities. Patel, who does work to increase the youth vote here in the U.S., hopes to incorporate these lessons into her own activism.

“I’ve always realized that it’s not just about voting,” Patel says. “But I think that seeing these students participating in Ukraine made me realize that when I do work in the U.S. it needs to be more about building communities and building community culture.”

Hope and Energy

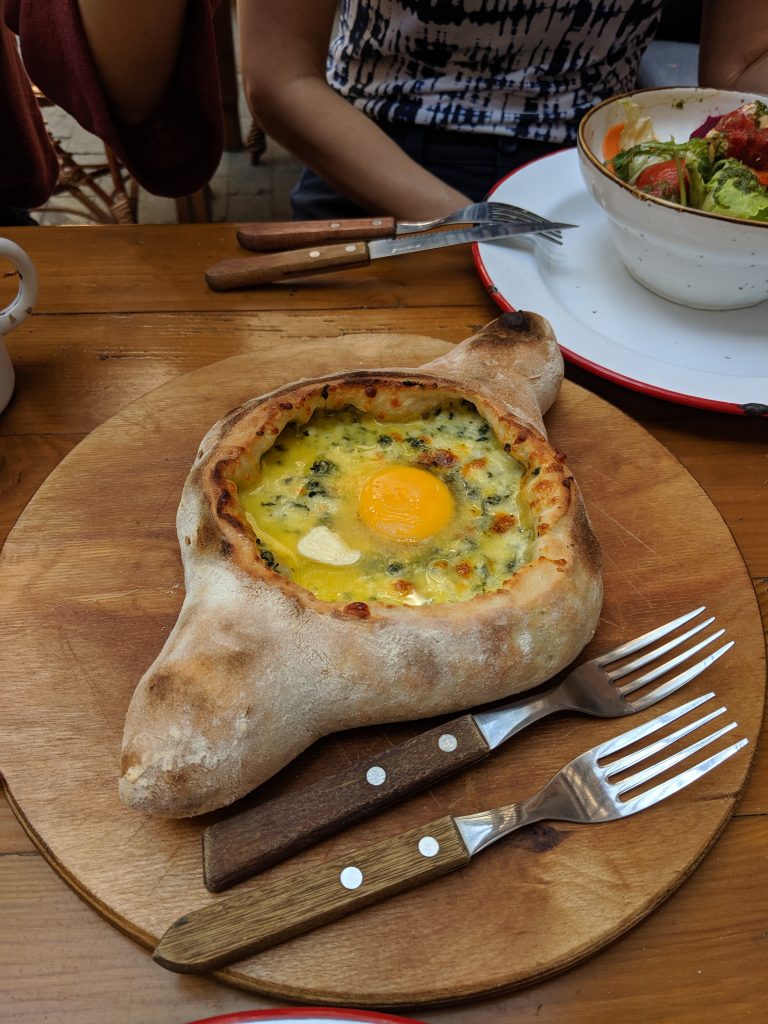

In between their research, the UT Austin group found time to enjoy Ukraine, exploring the culturally distinct cities of Odessa, Kyiv, Lviv and Ivano-Frankivsk, as well as taking excursions to a mountain village and the Black Sea. They were also able to socialize outside of the focus groups with their Ukrainian peers, giving both groups greater insight into each other’s countries.

Despite Ukrainian students’ expressed frustrations with their government, they were not entirely despondent. In a survey question asking what motivated them to vote in the election, “hope” was the clear winner (beating out negative options such as “fear” and “disgust” by a significant margin).

“One of the [UT Austin] students wrote an essay for the class,” says Neuburger. “About how on the one hand it seems that there’s no hope and it’s really dark, in a lot of students’ answers to the surveys answers and the things they said, but then on the other hand we keep finding this real hope and energy for change. And I think Zelensky did galvanize that.”