The discovery of a near 3,000-year-old platform, built among wetlands and rivers of the Mexican tropical forest, offers new insight into the Maya’s early communal development.

The site, called Aguada Fénix, is the earliest and largest known monumental structure built by the Maya and challenges the existing narrative that the Maya civilization developed gradually, with small villages emerging during the Middle Preclassic period (1,000–350 B.C.). The latest findings are detailed in a Nature paper.

“This mega platform is among the largest edifices built in Pre-Hispanic America and the biggest in the Maya world thus far found, yet it dates to the earliest phase of Maya history,” says University of Texas at Austin geographer Timothy Beach, a co-author on the study. “It was huge, it was early, it was Maya as separate from Olmec and other cultures, and it was built with incredible labor, all of which are teeming with implications.”

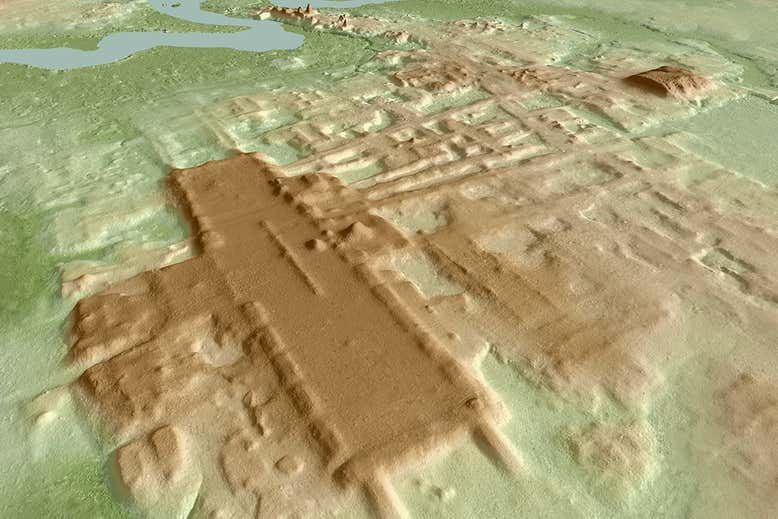

The researchers, led by University of Arizona archaeologist Takeshi Inomata, discovered the previously unknown Maya site in Tabasco, Mexico by conducting an airborne LIDAR survey, a remote-sensing method using lasers to create a 3D map of the earth’s surface, combined with intensive excavations.

Aguada Fénix sits 10–15 meters above the surrounding area, measuring 1,413 meters north to south and 399 meters east to west, with nine tracks extending from its sides. Through carbon dating, the researchers determined the structure was built between 1,000 and 800 B.C.

“This shows that Maya culture was already formed and complex in several ways near its start rather than gradually over its first millennium, somewhere around 3,000 to 2,000 years ago,” says Beach, who analyzed the region’s soils, water quality and wetlands. “At the inception of Maya history, some great centrifugal, societal force brought the earliest Maya groups together around a huge and unifying project to build a structure larger than any they would build again”

Aguada Fénix is unique from other archaeological sites from around the same period in important ways, the researchers note. First, its lack of clear indicators of social inequality, such as sculptures of high-status individuals, suggests the importance of communal work in the initial development of the Maya civilization. Secondly, excavations from the site showed hints of “remarkable” and intentional patterns.

“Clearly the early Maya builders were creating these patterns with different colored sources for some purpose,” says Beach. Through field work and analyses carried out in the Soils & Geoarchaeology Lab and Environmental Hydrology and Water Quality Lab, Beach and UT Austin student researchers were able to determine the sources of the various soils.

“We are analyzing essential soil chemistry, physics, and organics to understand the nature of the different colored soil mosaics that build up this massive platform,” Beach says. “Any good article answers some questions but raises many more, which we are pursuing.”

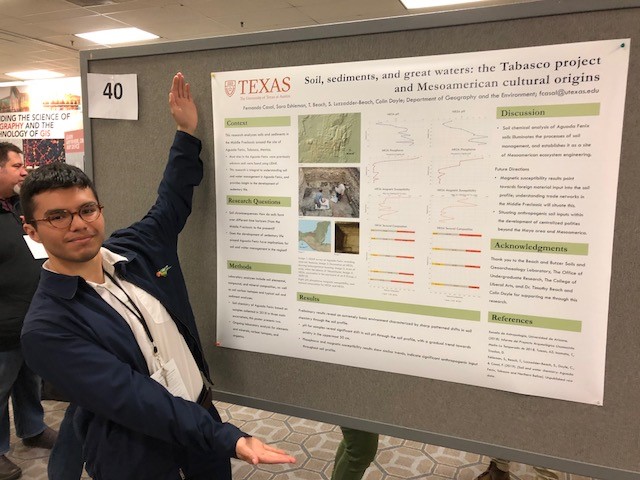

Recent UT Austin geography graduate Fernando Casal presented the soil and water analyses last year to the American Association of Geographers, and alongside Beach to the Society for American Archaeology. Given current pandemic circumstances and travel advisories, Inomata has collected more soil samples for Beach’s lab to analyze when work can resume, at which point UT Austin geography professor Sheryl Luzzadder-Beach will conduct further studies on the region’s water chemistry. Working remotely, Leila Donn, UT Austin doctoral candidate in Geography and the Environment, is using machine learning (AI) on the LIDAR images to detect other ancient sites that may have been overlooked.