In 2014, Maro Youssef arrived in Tunisia just one day before the country passed a constitution that is among the most progressive in the world. She was serving as a foreign affairs analyst at the American embassy in Tunisia.

The post was a culmination of eight years of work with the U.S. Department of State. Having studied the country’s evolving young democracy from Washington D.C., the chance to observe it on the ground was an important juncture in her research.

“No matter how much you know a country, if you are not physically located there, it is hard to grasp the complexities and nuances,” says Youssef, now a sociology doctoral student at UT Austin.

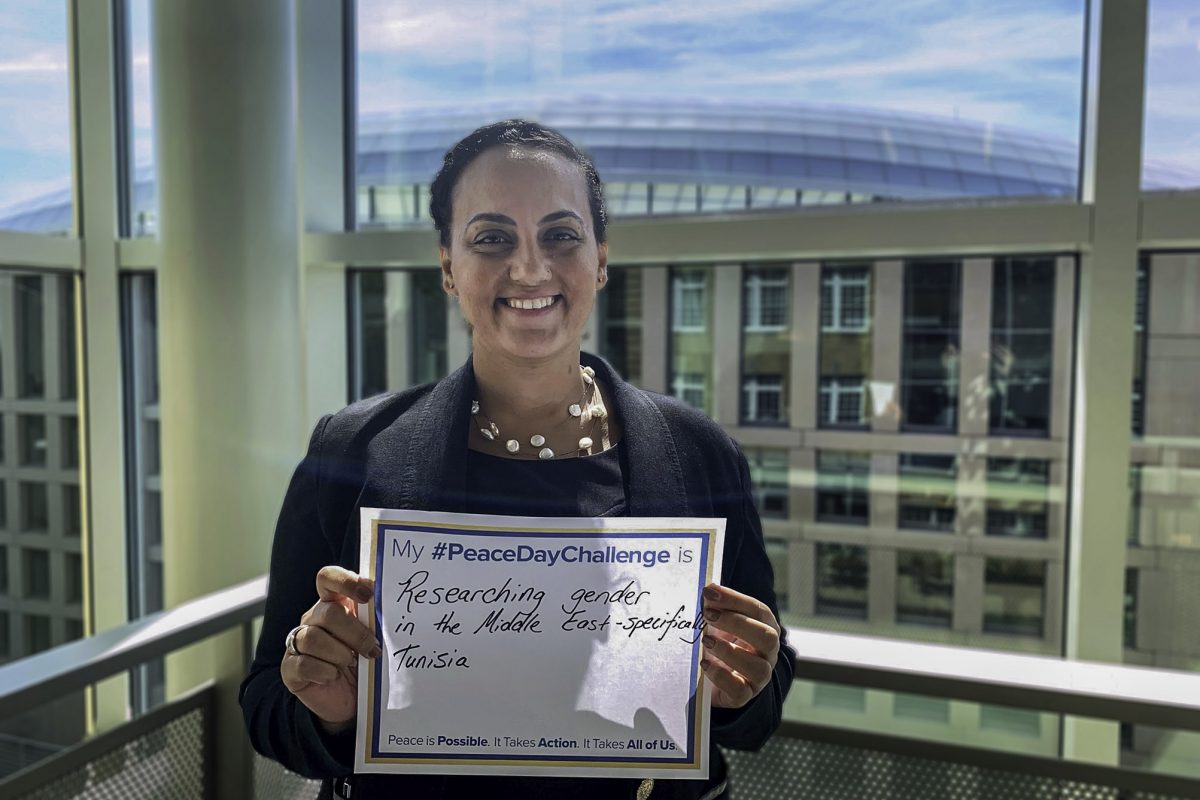

Youssef’s doctoral research focuses on Islamist and secular feminist women’s associations that formed in the wake of Tunisia’s 2010-2011 Jasmine Revolution and uses fieldwork and interviews with Tunisian activists. Last year she was awarded a U.S. Institute of Peace (USIP) Peace Scholar Fellowship, which will allow her to work fulltime on analyzing her fieldwork and completing her dissertation.

Tunisia, for those who don’t recall, is the country that launched the Arab Spring with a revolution that resulted in the ouster of longtime authoritarian president Zine El Abidine Ben Ali in January 2011. The transition to democracy was an opportunity to advance civil rights of its citizens, but it also threatened to destabilize the status of Tunisian women, who had enjoyed political, economic, social and legal rights since the 1950s.

While studying Tunisia during her time with the American embassy, Youssef took an interest in the work of Mounira M. Charrad, an associate professor of sociology at UT Austin and an expert on women’s rights and women’s movements in the country. Youssef accompanied Charrad on a trip to Tunisia to interview feminist activists. Charrad, who is now Youssef’s dissertation advisor, was a primary factor in Youssef’s decision to pursue her doctorate at UT. Through these interviews, Youssef came to understand how women helped to shape the country’s progressive constitution, which includes provisions for religious freedom and women’s rights.

The fieldwork was sometimes challenging, Youssef explains, as gaining the trust of the people she interviewed took time and patience. But the work was essential to understanding the enormous role of women in the design of Tunisia’s constitution. Women fought to protect and expand their rights despite challenges from conservative voices trying to undermine them, and they succeeded through persistent activism.

“Women activists played a key role in the progressive gender legislation they have in Tunisia today,” says Youssef. “They participated in civil society and in the government, which allowed them to have their voices heard by policymakers tasked with designing new gender policies.”

“Secular feminist and Islamist women’s associations have a common ground. It’s to make sure women enjoy equal rights.”

Maro Youssef

The post-revolution period saw a boom in the formation of women’s associations in Tunisia. During the authoritarian Ben Ali regime, only two secular women’s associations were permitted to operate. Since his removal from office hundreds of additional groups have formed, both secular and Islamist in nature.

Tunisia, Youssef explains, is not unlike the U.S. in that it is currently divided along liberal and conservative lines with often opposing agendas. However, both secular and Islamist women’s groups have contributed to the expansion of women’s rights in Tunisian society.

“Secular feminist and Islamist women’s associations have a common ground,” she says. “It’s to make sure women enjoy equal rights.”

Women in the U.S. can learn from women’s activism in Tunisia, she says, as they too are now at a crossroads where their rights can either be protected and advanced or diminished.

“The first Women’s March in 2017 resembled Tunisian style organizing around women’s rights. Women went out into the streets to express their concerns over their rights following a presidential election,” she says. “We can do more of that to make sure there is no backsliding on our rights, just like Tunisians did, starting in 2011.”

Youssef’s work in Tunisia was the intersection of parallel ambitions she’s had since childhood. The first is an interest in diplomacy, passed down at age six from her grandfather, who served at the Italian embassy in Cairo. The second is the goal of earning a doctoral degree, inspired by an uncle.

In the future, she also hopes to run for U.S. Congress in order to help reform immigration, education, and healthcare and also to work on women’s issues.