Add living a longer life to the list of reasons to move to Hawaii, which tops the list in a national study on average life expectancy. The study showed that living somewhere with more economic regulations and policy protections for marginalized groups may be the key for a clean bill of health.

“We run the gamut from the third-world to the first-world in our states,” says study co-author Mark Hayward, a sociology professor at The University of Texas at Austin. In 2016, average life expectancy in Hawaii was 82 years, compared to 75 in Mississippi. If the states were nations, Hayward explains, Mississippi’s life expectancy would rank 89th in the world between Bulgaria and Kuwait; and Hawaii would rank 19th among the likes of Sweden, Iceland, Canada.

These stark differences across states motivated Hayward and a national team of demographers, medical doctors and political scientists to conduct a national study on legal epidemiology, asking, “What are the kinds of laws and policies that have explicit or even indirect consequences for people’s health?” Their findings were published this week in Milbank Quarterly.

The researchers looked at the impacts of education policies, wage policies, economic policies, environmental policies — “All of those types of policies kind of shape the opportunities and resources and risks that people face in their daily life,” Hayward explains. What his team discovered is detailed in the Q&A with Hayward below:

Does a long life mean a good life?

Hayward: You can think about life expectancy as a mirror on the quality of life that people are living. So, it mirrors the resources and the risks that people face, the qualities that affect people’s opportunities to put together a good life — their economic resources, their ability to form healthy positive relationships, engage in positive health habits and protect themselves from risks.

Which countries have the best life expectancy? And which countries have the worst?

Japan, Singapore, Spain, Italy and Switzerland all have the best life expectancies. But there is a variety of countries that sneak into the top 10, such as Iceland and Australia, which tells you that there’s no one pathway to a long life, in terms of specific policies. But there are general orientations of societies that invest in their populations.

And in the worst, we have places like Chad, Afghanistan, Gabon, Swaziland and Somalia. These are places where life is chaotic, there are few resources, there are many risks in the environment and people have a difficult time putting their lives together.

Why is there such a discrepancy in life expectancy across U.S. states? Do we see this anywhere else?

There are some countries that have a lot of large regional differences. But the United States is unique in the extremes of its life expectancies. Within Europe, the only place that has these kinds of discrepancies is the United Kingdom. Scotland has quite low levels of life expectancy.

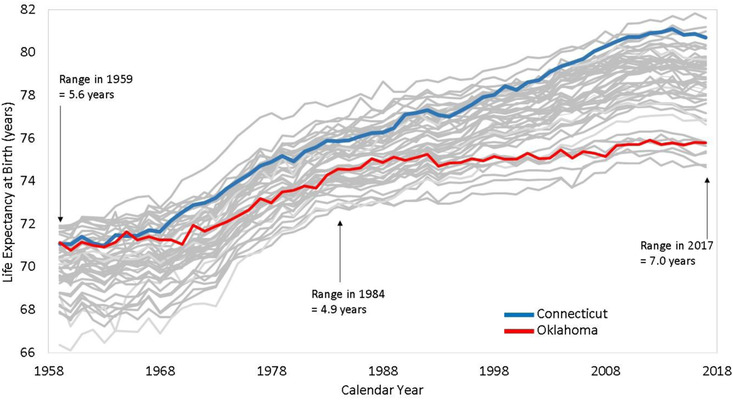

We have 50 states responsible for a variety of policies that affect everyone’s lives, from birth to death. When you have 50 states that do this and they have different agendas and different patterns of development, over time those differences are going to grow. And that is exactly what happened in the United States.

Source: United States Mortality Database.

Part of this was caused by the devolution revolution of the 1980s, which defended states’ rights in the development of their own policies from the feds. But then, we saw the development of political movements and very conservative groups engaged in, essentially, state capture.

There were lobbyist groups that are well-funded by private resources that develop conservative agendas and put them into play — the same agendas and wording — across 26 states at one time. So, what we saw over that time period were one set of states in the south became increasingly homogeneous.

But they were not as well off. In fact, some of those states used to be very well-off in terms of life expectancy. But this pattern of state capture, I would call it, is really this legislative agenda that is more focused on economic freedom, which is the expansion of rights for corporation that often comes at the expense of individuals.

What types of policies tend to improve life expectancy?

The policies, such as the deregulation of industries within states, have very harmful effects on populations because they lose their jobs. You’ve heard in the news, people aren’t able to garner a good wage; some states refuse and block efforts in terms of raising the minimum wage.

So that what you have is a set of individuals at the state level that have relatively less power than organized groups. And that less power translates to a lower quality of life and much more economic insecurity, and much more difficult time in putting a quality of life together over a long time.

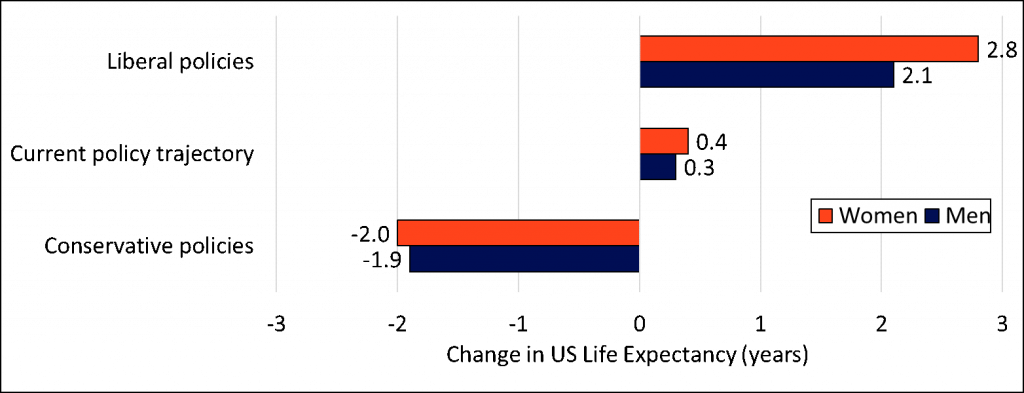

I will say there is no one specific portfolio that leads to one outcome as opposed to another. States with a longer life expectancy, what they have in common is they have more liberal policies — meaning, the expansion of economic regulations and the protection of marginalized groups. California has done a lot of that, New York, Massachusetts. All of those states’ populations began to climb and improve.

And I would say, that’s kind of the key criteria that cuts across states and separates people that are able to put together quality lives and have longer life expectancy than other areas where they’re much more vulnerable.

Source: Syracuse University policy brief, “Conservative State Policies Damage U.S. Life Expectancy.”

Looking ahead to the November elections, what should voters consider?

I’m passionate about improving people’s lives and improving their life chances, so you have to put my recommendation in that context. You don’t have to care about parties. But you do have to care about people and candidates that are committed to policies that invest in people’s well-being broadly speaking.

I want to go back to this idea that there’s not one magical portfolio. But policies do tend to cluster, and there are policies that invest and there are policies that literally de-invest in their populations and put people in harm’s way.

Knowing this, how can the government improve its response to the current pandemic?

My team had a Zoom meeting not too long ago, and we thought, “Could we have a better case study of what not to do during a pandemic?” It’s this question about no federal leadership, no federal resources and no guidance — and in fact chaos and contradicting information — putting total responsibility back on the states, which are unprepared to be dealing with this pandemic.

I wasn’t kidding when I said we have 50 states that are functioning like 50 countries. And in terms of the pandemic, we have 50 countries who are not fighting this in a coordinated way and it’s already had negative consequences. So, I’m not optimistic in terms of what’s going to be happening in the near future.