When people travel to the United States, they might be shocked at how large our portion sizes are, how friendly strangers may seem or how informal and direct conversations tend to be.

These types of surprises can cause cultural shock, a common feeling that many people experience when traveling abroad or connecting with new cultures. But simply recognizing these differences and where they stem from can go a long way in relieving cultural tensions.

Enter The University of Texas at Austin LESCANT database, an archive of mostly student-submitted photographs from around the world that capture and categorize cultural differences in the areas of Language, Environment, Social Organization, Context, Authority, Non-Verbal and Time. The database adheres to the LESCANT model, which was developed in the 1990s as a way to improve international business communications.

“Without the model, many of these cultural issues go unnoticed,” says Orlando Kelm, a Spanish and Portuguese professor at The University of Texas at Austin. “When we understand the model, we become active observers looking for examples of the cultural issues. The database becomes the training ground to learn how to observe, which leads to a richer experience when we are out in the real world.”

Kelm, also an avid photographer, created the database for students to meet cultural confusion with reflection. To show how it works, Kelm breaks down the LESCANT model to explain how life as we know it in the U.S. might seem a bit weird to those who are visiting:

Language

Even if someone has taken the time to study and practice a culture’s language, issues can still arise depending on a culture’s relationship to the language. These little idiosyncrasies can show up in slang, puns, translations or even in business names that might be confusing or go under appreciated.

“The restaurant named Gourdough’s, for example, tells us so much about Texas culture and its Latin American influence,” Kelm says. “You can’t understand the name of the restaurant if you don’t know that the Spanish word for fat is ‘gordo’ and if you don’t get the wordplay with ‘gourmet’ and ‘dough.’”

If you can understand all of that, then you aren’t so surprised when you get a menu featuring a hamburger between two donut buns.

Environment

Lots of us travel to experience new surroundings, to see things we haven’t seen before and to eat things we haven’t eaten before. But some differences in climate, population density or even the temperature of the drinks or parts of animals we’re expected to eat can leave us feeling uncomfortable.

“People from other countries just can’t believe the size of our servings,” Kelm explains. “We can learn a lot about U.S. culture when we see the absurd portion sizes — a land of plenty!”

Social Organization

When we consider ideas of democracy, socialism, federalism, etc., we understand how places are governed differently. But cultures are made up of much more organized structures than government alone. These structures might put emphasis on certain types of relationships, genders, social classes or religions.

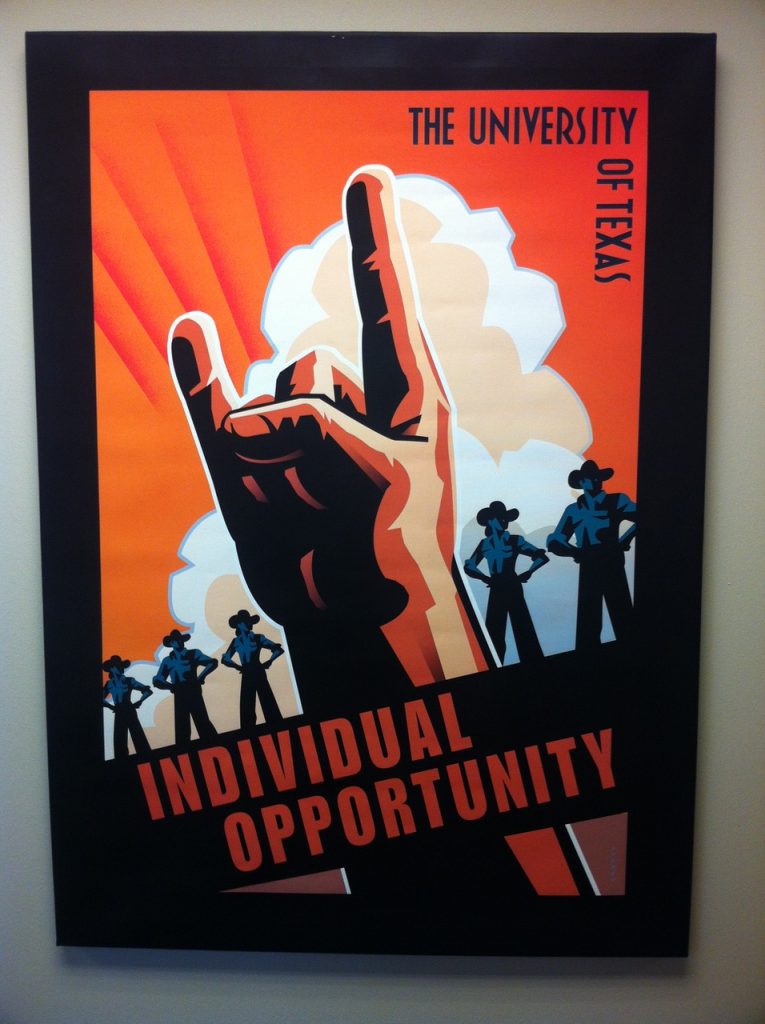

“Here at UT Austin we take pride in providing individual opportunities, not realizing that for most of the world, our quest for individual opportunity is seen as selfishness,” Kelm offers.

Context

Do rules govern behavior or does the situation guide you? In some low-context cultures, like the U.S., we rely on words alone, whereas high context cultures focus on situations and shared knowledge to determine appropriate behaviors.

“Here in the U.S. we give rules with no context or explanation, simply a gigantic list of rules,” Kelm says. “In most of the world we find ‘rules’ that come with some type of description and reasoning.”

Authority

How are decisions made and who makes them? From the presidency to department leadership in universities, the U.S. tends to exchange power, opening up more opportunities for leadership and changing the way we view and relate to those in power. In other cultures, power may be more long term.

“This statue from Fredricksburg honors a military figure, with casual clothing and an informal pose,” Kelm describes. “This is shocking to people from other places in the world, who only see military statues in formal positions, on a horse, sword in hand. It shows our approach to downplay formality in showing authority — because everyone is created equal.”

Non-Verbal

Non-verbal communication shows up in the way we dress, touch, smell, in the hand gestures and facial expressions we make or even the lucky numbers we put our faith in.

“This bench is at the carriage ride in South Carolina. Imagine not being from the U.S. and trying to figure out the non-verbal message of this sign,” Kelm points out.

Time

Cultures around the world organize their days and weeks differently, from when they work, to when they eat, sleep or do absolutely nothing. The U.S. is unlike many other places in the world in the way that we divide and compartmentalize our time.

Kelm reflects on the astonishment many of his out-of-country guests have when visiting popular BBQ joints: “I have taken a number of foreign visitors to the Salt Lick. Almost every time someone notices this sign, and they are shocked to see that people are told when to leave a restaurant!”