During her annual trip to France with students in the Normandy Scholars program in 2008, Judith Coffin, an associate professor of history at The University of Texas at Austin, visited the manuscripts collection at the Bibliothèque nationale de France (BNF) in search of letters.

While conducting research for a project, she had come across a footnote that mentioned letters written to Simone de Beauvoir. The letters were in Beauvoir’s archive — a collection of letters, manuscripts and other personal documents — at the BNF. However, no record of the letters existed in the finding aids. When Coffin reached out to the supervising curator to inquire about the letters, she had no idea they would occupy the next decade of her life.

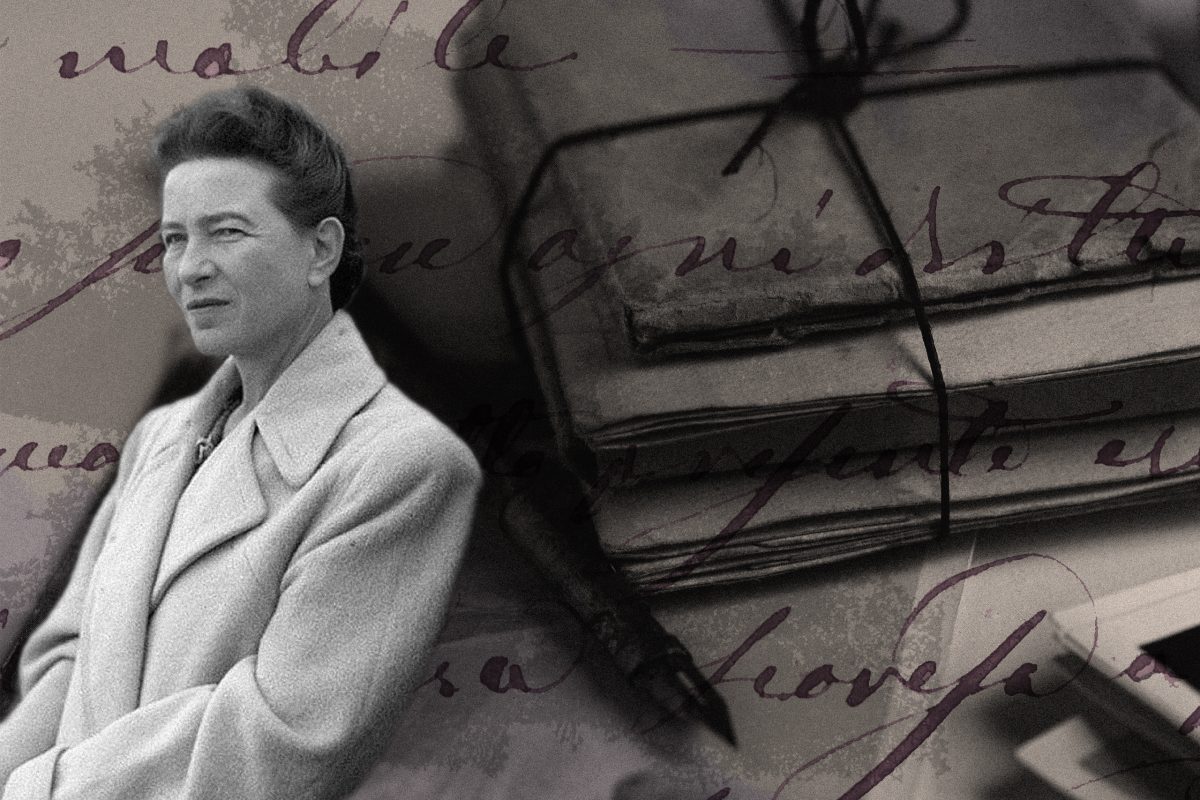

Simone de Beauvoir is perhaps best known to American audiences as the author of The Second Sex (1949) or as the longtime partner of Jean-Paul Sartre. But during her lifetime (1908-1986), Beauvoir authored over a dozen literary works, including four volumes of memoir. Coffin describes Beauvoir as a “fearless, difficult, and brilliant French feminist” who belongs to a tradition of public intellectualism in France that dates back to the Enlightenment.

Readers did not just appreciate Beauvoir’s writing, they also saw it as an invitation to converse. A Belgian middle school teacher wrote her, “The wisdom of your observations, the courage and the generosity of your intellectual position show that you clearly can recognize the importance of the subject of my letter.” Many readers shared these sentiments. They saw Beauvoir as a role model, but also a warm and challenging interlocutor.

In Sex, Love, and Letters: Writing Simone de Beauvoir (2020), Coffin traces correspondence sent to Beauvoir between 1949 and 1972, a period marked by events like the Algerian War, the student movements of 1968, gay liberation, and second wave feminism. People would write saying, “Like you, I lived through this specific experience.” And Beauvoir would regularly respond, although Coffin could only infer the details of those responses.* The letters arrived from nearly every continent, and from famous and ordinary fans alike. Their contents ranged from enthusiastic notes on Beauvoir’s work to requests for marital and parental advice. (Beauvoir was an improbable expert on both subjects. She never married, never had children, and was polyamorous). Of course, some letter-writers chastised Beauvoir for her progressive stances: “What is going to happen if my future daughter-in-law becomes enthralled with your work?” a concerned letter-writer queried on August 3, 1966.

“Beauvoir persuaded people that everything in their lives was significant – how they made decisions, or what we might call the micro-politics of everyday life.”

Judith Coffin

Over the course of her career, Beauvoir saved thousands and thousands of letters from readers. “Beauvoir persuaded people that everything in their lives was significant – how they made decisions, or what we might call the micro-politics of everyday life.” Coffin continues, “Their ideas were significant as well. [Writing to Beauvoir] was an invitation to think of yourself as a thinker. These letters show that thinking isn’t just for philosophers. These ordinary people were full of ideas and hungry for intellectual conversation.”

The intimacy between Beauvoir and her reading public might be shocking to those familiar with her work and public persona. Beauvoir could be aloof or stern. These readers loved her anyway. She wrote a short story, The Woman Destroyed, about a woman whose marriage was falling apart. It was based in part on letters she had received from readers. The woman character wasn’t very sympathetic; she seems clueless. And many readers wrote to thank Beauvoir for writing about them! “Sometimes they talked past each other. It’s like a marriage itself,” Coffin jests.

Since the book’s publication, Coffin has received emails from people sharing pictures of their letters from Beauvoir, “They want to send me pictures of the letter and talk about their relationship with her, or how they met her and how friendly she was.” Beauvoir’s correspondence with her fans reveals how she created a global community that continues today.

Join the conversation by reading Sex, Love, and Letters. Enjoy the fascinating insight into everyday lives and thoughts.

*Many volumes have been published with Simone de Beauvoir’s letters to her romantic partners. You can find her letters to Nelson Algren in A Transatlantic Love Affair, to Jean-Paul Sartre in Letters to Sartre, to Claude Lanzmann at Yale’s Beinecke Library. More recently, one of Beauvoir’s many faithful readers has published her letters: Blossom Margaret Douthat, Un amour de la route: Lettres à Simone de Beauvoir.