Before his research helped discover the healing powers of writing and the Secret Life of Pronouns, Jamie Pennebaker’s curiosity killed the crab.

It was a harmless prank that he and his friends would play, inspired by the show Candid Camera. They’d put a rotting crab claw in a box, wrap it up nicely with a big red bow, place it on a busy intersection, then hide behind a bush to see who’d take the bait.

Pennebaker remembers one woman, filled with guilt and excitement, jumping out of her car, furtively looked around, then jetting off with her prize. “I wonder what people did with all those stolen crab claws?” he jokes.

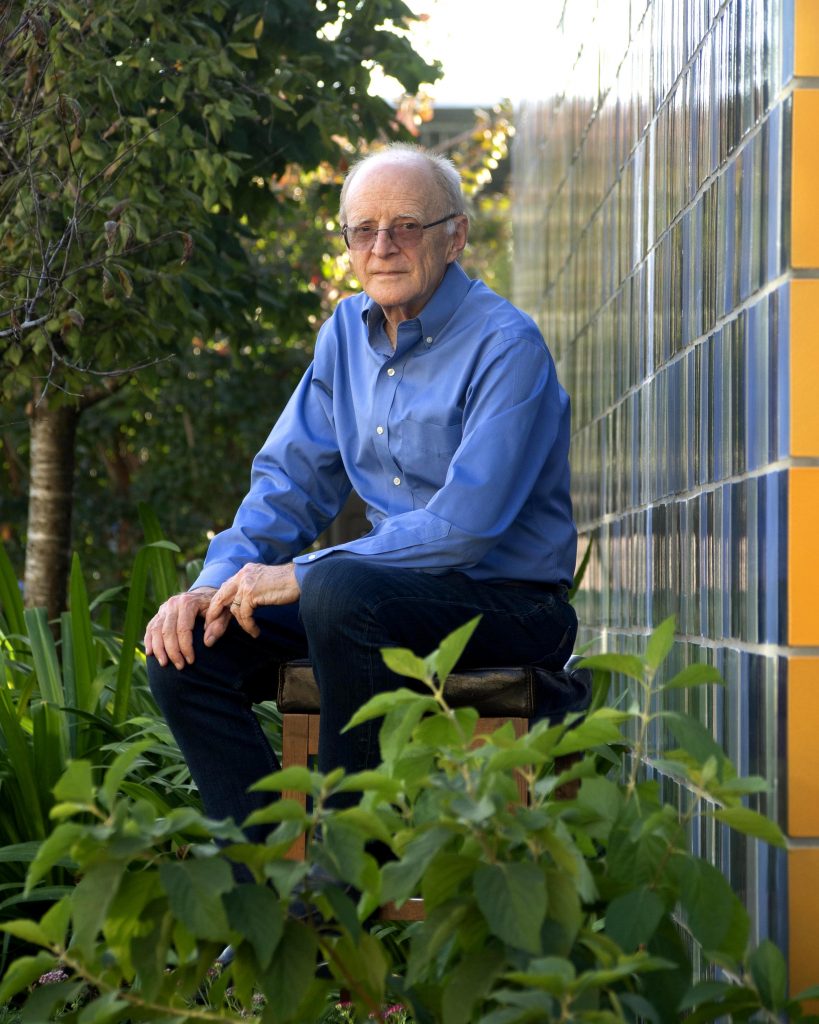

Looking back, Pennebaker says these playful set-ups may have primed him for his life’s work as a social psychologist — a groundbreaking career that recently received high accolades from the Association for Psychological Sciences (APS) through the William James Fellow Award.

The association’s oldest award recognizes Pennebaker, a professor at The University of Texas at Austin, for a lifetime of significant intellectual contributions to the basic science of psychology. But with 40 years of work culminating into 12 books and more than 300 journal articles that have shaped the fields of psychology, linguistics, sociology, medicine, communications and computer science (to name a few), Pennebaker’s contributions are “on par with what one could consider significant for two lifetimes,” argues Matthias Mehl, a psychology professor at the University of Arizona.

Pennebaker is, perhaps, best known for his work on expressive writing.

“It’s hard to imagine that there are psychological scientists in the field who are not familiar with Jamie’s writing paradigm,” Mehl says. “It provided an ingenious way to bring basic — one could even say ‘ancient’ — ideas about how emotional processing can affect health into a lab setting.”

Originally from Germany, Mehl says he was “catapulted” across the Atlantic to Pennebaker’s lab more than 20 years ago after reading Opening Up by Writing it Down, Pennebaker’s popular science book — now in its third edition — about how writing can be therapeutic.

“The time in his lab was so special, so intellectually inspiring, so full of excitement about conducting research that matters, that my intended one-year study abroad fellowship effectively became Jamie-induced immigration,” says Mehl, who completed his Ph.D. at UT Austin under Pennebaker’s mentorship in 2004.

Pennebaker’s work offered new insights into the mind-body connection, it provided evidence on the dangers of silence and secrets, and empowered others to explore the influence of emotional expression through both practice and research.

“I wanted to study expressive disclosure the way Jamie was studying it because, at first, I didn’t believe his results — they were astounding,” says Annette Stanton, a Distinguished Professor of Psychology at the University of California, Los Angeles.

She recalls Pennebaker’s earliest study on the topic, where he invited students who had suffered trauma into his lab to share their experiences and emotions through four, short writing sessions. After the study, the students who participated in the “narrative processing” exercise were half as likely to go to the student clinic than their peers — a finding met by surprise and skepticism from his colleagues, making the study “hell to publish,” Pennebaker admits.

The idea for the groundbreaking experiment came from a side-finding in an earlier study he did related to The Psychology of Physical Symptoms, where he noted that people who kept secrets, especially related to trauma, were more likely to get sick. So, Pennebaker’s thought was to set-up a space for them to let it all out and, for the first time, effectively measure the influence of emotional expression.

“You can tell he has this natural sense to want to learn,” Stanton says. “Jamie’s careful methodology was incredibly innovative, and it had extraordinary influence across a number of fields.”

After reading his studies, Stanton reached out to Pennebaker to be a consultant for a study on stress in women with breast cancer. She has since employed his methods on a number of other studies, including one on students and financial stress. Hundreds of labs have tested his ideas on emotional disclosure.

“This is where most scientists would think ‘ok that’s plenty, in fact more than enough for an outstanding scientific career,’” Mehl jokes. “But what happened over the last 20 years is, in one word, astonishing.”

Immersed in his studies on expressive writing, Pennebaker began studying participants’ essays word-by-word, trying to predict who would benefit most the writing sessions and carefully divulging what certain words said about a person’s inner-most thoughts, emotions and behaviors.

To speed up this time-consuming analysis, Pennebaker partnered with a graduate student, Martha Francis, and brushed up on some of the Fortran knowledge he acquired in his brief stint in the computer science world in college. They created the first text analysis software called LIWC (Linguistic Inquiry and Word Count) in the early 90s.

Each night, he tested the software by downloading AOL chats and running the online conversations through the program.

“I discovered that language didn’t work the way that I thought it would,” Pennebaker says, describing the individual differences and personalities that shine through the simplest of words. “In psychology we usually look at individuals, focus on how a particular person is behaving. With language, everything changes. We can now look at entire communities and cultures.”

In the last couple of decades, Pennebaker has used LIWC in a number of different studies, publishing a plethora of intriguing insights on the psychological meanings behind words. With his graduate students, he has been exploring how language can identify underlying psychological states, community values and cultural shifts, what it reveals about group dynamics, song lyrics, or even how political leaders think and feel.

And the simple, yet ingenious software continues to be used by people studying psychology, history, medicine, marketing, linguistics, computer science and even by tech giants to understand their branding and improve problems with customer service.

Most recently, Pennebaker and his students have used the program to monitor cultural shifts during the COVID-19 pandemic. By analyzing millions of comments within the social media site Reddit over the last 10 years, Pennebaker’s team is witnessing the profound psychological changes that accompany significant social moments, like the global pandemic, Black Lives Matter or the past presidential elections.

“Because words are everywhere, we are able to see the world in ways we’ve never imagined,” Pennbaker describes. “I feel as though I couldn’t have picked a discipline that is more interesting or in a time that’s more dynamic because it deals with all of us — our connections and how we feel about ourselves and the world.

“So, what’s next? Who knows. My guess is there will be something in it for a good researcher.”