I’ve just been reading about the relationship between time and space inherent to many indigenous cultures in a book called On Trails, by Robert Moor, which explores the evolution and meaning of trails of all kinds, including long-lost Cherokee trails in the eastern U.S.. In fact, there’s a word for it: topogeny, or the ritual association of place names with memories. Put another way, imagine time is like a landscape, and recalling a memory is like traversing physical space in the mind’s eye. At least, this is my introductory understanding of the concept.

Ordinarily, this complex reality in which time is understood topographically and space is understood temporally might be a difficult concept to grasp, but I find that in the context of quarantine it makes absolute sense. How else can I wrap my head around time’s sudden elastic quality, wherein days feel like weeks, weeks feel like months, and months, oddly, feel like days, and back around again, but through stretching them out over a vast landscape? Days that are entirely absent of geographic variation have the effect of an endless sea in which we’re being pulled by some unseen current. We all drift slowly, steadily, but little do we know how many miles this way or that. In other moments, time has had the audacity to stand still when we’d very much prefer to continue moving, and faster please. The election managed to turn an entire week into an impassable mountain range in the geography of my memory, for who could remember anything that happened before November 3? My mind’s eye is only just starting to recover from the sudden myopia.

Call all this fuss about time a workplace hazard. It’s the 50th Anniversary of the Center for Mexican American Studies (CMAS) at The University of Texas at Austin, so I have a professional obligation to celebrate time, no matter how cruel it may feel this year. Luckily, CMAS Director John Morán González, helped trace some of our legacy in a message last month in which we announced the official postponement of Movidas, an event that we had envisioned to be an academic conference for the community held at Austin’s Central Library:

Fifty years of Latino Studies on campus is a huge achievement, even for institutions as long-lived as Universities. Fifty years of representing the experiences and knowledge of Mexican American and other Latino communities in Texas, who had long been excluded in significant numbers from the state flagship prior to 1970. Fifty years of speaking truth to power, and thereby fighting for equity, inclusion, and democracy. Fifty years of working for the success of all students, but especially Latinx students, for whom Latino Studies has been a cultural oasis and a space of affirmation. Put differently, the presence of Latino Studies means that Latinx communities truly matter in the University’s business of knowledge-production.

Surely this legacy has earned us a party or two, we thought. It was tempting, even, to feel like we were owed the fanfare. But of course these are not the times for parties, and as for what we’re owed, it’s best to remember that many are still owed quite a lot in the midst of this pandemic, no doubt a great deal more than us. Yes, with every celebratory event either cancelled or postponed, it was starting to feel like everyone would rather this milestone, and all others for that matter, passed quietly without much ado. I’ll admit that even I felt this way some days.

So, topographically, what would that make 2020? An empty plain? An unmarked trail? A sinkhole?

Since the establishment of the Center for Mexican American Studies fifty years ago, we’ve faced wars, epidemics, state violence and more, over and over again. Across these many years are historical contours that, like the land, have been battered by crashing waves, river rapids, sea change, and not all of it metaphorical. To not acknowledge this milestone would be like letting the total landscape of our collective memories slip into a black hole, for it wouldn’t just be 2020 we’d be losing to gravity but also the inextricable decades that trail behind it, decades that are fundamental to who we are as both an academic department and as a future Hispanic-Serving Institution.

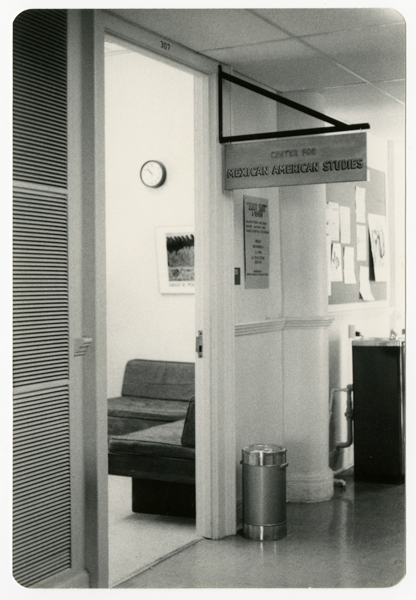

No, when places disappear, it’s not because they’ve simply leapt off the map. Land is stolen, towns are renamed, trails are widened, paved and turned into interstates, but there they are still, on a faraway hill many years behind us. If time works the way I think it does, or perhaps the way I want it to, then once it’s there it’s always there, and true erasure is avoided if we hold onto a way back. Whether the footsteps are measured in miles or millennia, the return is mapped in our mind’s eye if the story lingers somewhere among us, passed on by our elders, told to each other, even acknowledged to ourselves. I can show you, for example, this picture of an empty hallway and a doorway beneath the old CMAS sign and you can clamor over half a century of memories, through decades and different buildings, past now-dusty classrooms that were once new, and somehow find your way back here to where it all began. But only if we tell the story.

So we can’t have a party, but maybe this is the perfect place, or point in time, to get our bearings: let’s honor the countless alumni, faculty and staff who have given so much of their precious time over these last fifty years to make us what we are today. Let’s relive the dramatic beginnings of the center and never take for granted how hard fought a beginning can be. Let’s remember together and walk our way back through to the past. Our impulse on such an occasion is to look forward, and rest assured we’re doing plenty of that, but it is in the very act of remembering that we preserve our future and ensure that, if we’re lucky, we never reach that horizon.