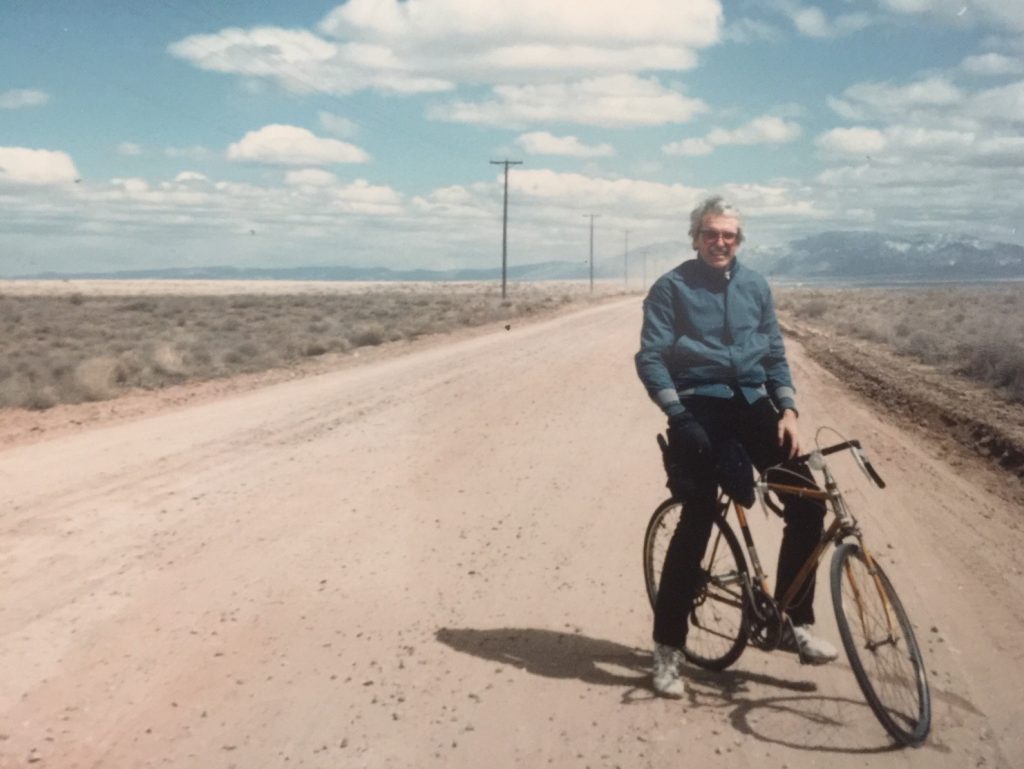

Peter LaSalle prides himself on traveling light. When packing for a trip he takes just two carry-on items. The first is a small gym bag with a few changes of clothes and other essentials. The second bag is filled with books.

The Susan Taylor McDaniel Regents Professor of Creative Writing at The University of Texas at Austin, LaSalle recently published his second collection of travel essays – The World is a Book, Indeed – chronicling his explorations of the places that give rise to literature he admires. LaSalle has been traveling in this manner since his college days, when as a Harvard undergrad he landed an assignment writing about Ireland for shoestring travel guide pioneers Let’s Go.

“In Ireland that summer I found myself more interested in tracking down literary spots there associated with Irish writers — Joyce, Yeats, the many important Irish playwrights — than seeking out hostels and pubs to recommend,” says LaSalle.

That summer wandering through Ireland’s literary history laid the groundwork for LaSalle’s current travel narratives, which are decidedly uninterested in serving as how-to books for readers assembling trip itineraries.

The short essay that starts The World is a Book, Indeed, set in late 1970s Boston, describes the author’s transcendent experience of reading Gabriel García Márquez’s The Autumn of the Patriarch for the first time, barely leaving the Beacon Hill apartment he’s staying in while outside a blizzard blankets the city in snow. This sets a tone for the rest of the collection. While he encounters better weather and interacts more with the largely urban settings he visits in the subsequent pages, it is always literature — the books, the authors and his fellow readers — that lies at the core of LaSalle’s tales.

“I’m not after straightforward travel writing of the type you find in Sunday newspapers or glossy magazines, or as the premiere American travel writer Paul Theroux himself so aptly describes such work, ‘the-ten-best-waterslides-on-cruise-ships’ school of travel writing,” LaSalle says. “I write what I trust are essays not articles, hopefully validly contemplative, also sometimes quite personal.”

The current collection spans multiple decades. One chapter finds LaSalle early in his career, landing in Cameroon to spend a summer interviewing local authors on a research grant despite having no credentials in the subject beyond a growing obsession with African literature. Closer to the present day he discusses Vietnamese novelist Bảo Ninh’s renowned novel The Sorrow of War over beers at a lively Hanoi bar with two military men from the country’s People’s Army who are also writers.

LaSalle’s essays feel less like travel writing and more like stories set in foreign locations. A writer of short stories and novels by trade, he uses many of the same narrative techniques from fiction in his travel essays, creating an experience that is immersive rather than simply instructive.

In a particularly expressive tale, LaSalle and a friend and fellow scholar of literature embark on a meandering nighttime drive through São Paulo, Brazil in search of the former home of a writer they’d discussed over dinner. In a similarly zigzagging manner, the narrative weaves together recollections of the evening itself, LaSalle’s memories of his friend’s time at UT and ultimately the painful story of his unexpected early death from cancer. Emerging from these many details is a meditation on the dreamlike aspects of memory and of storytelling contrasted with the harsh finality of death.

Several times throughout the book, LaSalle alludes to “serious” works of fiction as separate from more commercial pursuits, though he is wisely hesitant to impose rigid definitions on what he feels is a broad and debatable distinction.

“I guess that for me serious literature is essentially that which is, in fact, art, rather than mere entertainment. Which means it does offer a reading experience that definitely enlarges our lives in the oh-so-brief time any of us has on this sweet planet, humanizing for all concerned and in no way elitist,” he says. “It can do this in any number of fresh and engaging ways in fiction, among them the strong power of the insight about life itself contained within or the transport of the beauty in the language and structure of a work. It’s also work that lasts.”

One of LaSalle’s favorite purveyors of serious literature is the celebrated Argentine author Jorges Luis Borges, who eventually appears as the main character in one of the essays. This time, Borges himself is the traveler, spending a semester at UT Austin as a visiting lecturer in the early 1960s. Borges used fiction to challenge our assumptions about the nature of reality, which seems to inform some of LaSalle’s own musing on the fragile boundaries between reality and dreams, and between the experience of reading and the experience of living. As we witnessed in his Boston essay, great literature can transport the reader not only into another country but into another world.

Writing about Borges, LaSalle relays an anecdote of the author being challenged over his assertion that Austin is the most beautiful city in America, given that he was already nearly blind during the visit and surely saw very little of his surroundings. To which Borges responds, “I find it so beautiful because I dream well there.”

“I hope people are aware of how special UT and Austin became for Borges,” LaSalle notes. “In both my undergrad and grad classes, I always make it a point to work in some discussion of Borges. I want to make students aware of how their university once had on its faculty, if only for a semester, one of the undeniably major figures in world literature in the 20th century and that he subsequently had a lifelong affection for the university as well.”

One item not packed in LaSalle’s travel bag is a camera, as he prefers to record his experiences in notes rather than photographs.

“For the sort of traveling I do, I don’t trust cameras,” he explains. “They make everything too easy by letting the machine perform the work. I find the experience and details of a scene I encounter sink in much deeper, making me more involved, if I have to scribble notes, sometimes rather obsessively and stopping every ten feet or so on a sidewalk in a foreign city, almost CIA agent-style.”

These written details, crammed into the lines of cheap pocket notebooks, form the basis for LaSalle’s travel essays after he returns home, and in some cases for his fiction, which is increasingly set abroad.

Like many of us, LaSalle has been deprived of travel during the past year of COVID and he looks forward to being able to again take the kind of trips that give rise to his essay collections – trips spent wandering dense city streets, mingling with local writers, staying in budget hotels and eating in local restaurants rather than sanitized tourist spots. But perhaps the place he misses most is UT’s Perry-Castañeda Library (PCL), where he conducts his pre-travel research and which currently offers only limited access.

“I usually spend a few months immersing myself in the literature of another country — nonfiction books about the place, too — before any planned trip. After my afternoon classes wrap up at the end of the week, I head from Parlin Hall over to the upper floors of the PCL and get to work browsing in the stacks, sometimes a couple of hours there.”

LaSalle’s bags are always heavier when he returns from his journeys, weighed down by the many books he acquires along the way.