For the first time, researchers have recorded how the body responds when someone is confronted with racism or discrimination in the real world, providing new insight into health disparities in the United States and the stress experienced by students-of-color.

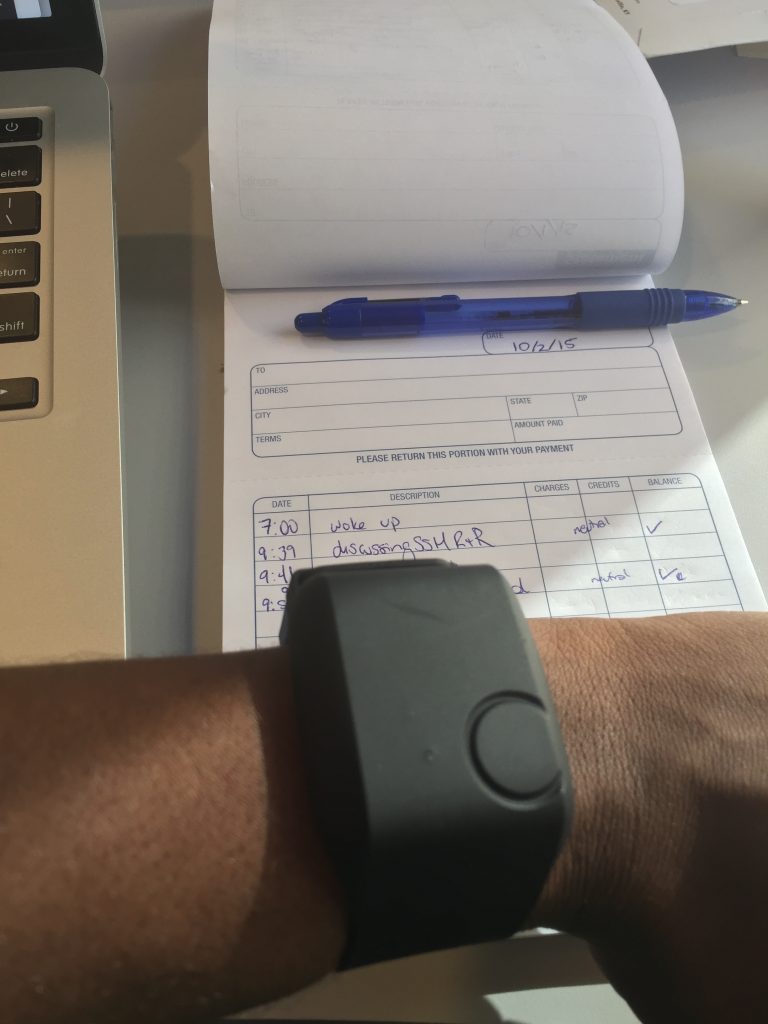

To measure the body’s real-time response to racism, 31 African-American, 24 Latinx, 25 international students from Africa, and 30 students from local refugee communities kept daily diaries for two weeks, documenting when they witnessed, thought about or experienced interpersonal racism. Researchers compared these experiences with data from the students’ wristbands, which tracked the body’s stress response through the detection of sweat — a key indicator of sympathetic nervous system activation, or stress response.

Their findings, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, add to the evidence that chronic stress from racism can lead wear and tear on the body and worsened health conditions for minorities.

“The United States has not been kind to many people of color, and these experiences influence the bodily responses that shape proneness to illness and disease,” says the study’s lead author Bridget Goosby, sociology professor at The University of Texas at Austin. “A lot of studies talk about the relationship between discrimination and health, but they don’t actually measure these experiences being written in the body as they happen.”

The findings for Latinx students were as predicted. Students showed heightened stress response when experiencing interpersonal discrimination and suppressed response when ruminating which suggests fatigue and depression. The researchers were surprised to find that Black students only showed heighted stress responses when they experienced interpersonal discrimination first-hand. And for international students from Africa, it was only when they ruminated on the topic.

“Being a minority in predominately white spaces adds additional burdens that impact bodies and negatively affect long-term health.”

Bridget Goosby, professor of sociology

The timing of the study is important in understanding these findings, the researchers said. The field work took place in 2016, before and during the presidential election.

“It was the height of the first wave of the Black Lives Matter movement, and we think it created space for comfort and support for African American students that might have been therapeutic,” Goosby says. “The Lantinx students’ experiences were closely tied to the election and anti-immigrant rhetoric. It was highly, highly stressful for them and this whole period will undoubtedly continue reverberating through their lives.”

The study, co-authored by Jacob Cheadle, professor of sociology at UT Austin, offers researchers more details around the frequency within which people experience racism and the impacts it can have on the body.

“I think that this study provides foundational and timely insights into how social stress gets under the skin to make people sick, particularly for those people who spend considerable time in primarily White settings, such as college students,” Goosby says. “Although many people focus on class and socioeconomic status as the roots of health inequities, being a minority in predominately white spaces adds additional burdens that impact bodies and negatively affect long-term health.”

At UT Austin, Goosby and Cheadle continue to examine how discrimination affects health in a pilot study for Whole Communities-Whole Health, led by Aprile Benner, associate professor of human development and family studies. By tracking the activity and health of 145 Black and Latinx adolescents, researchers aim to learn what research methods will provide the most layered, interconnected picture of health without asking too much of participant’s time and attention.