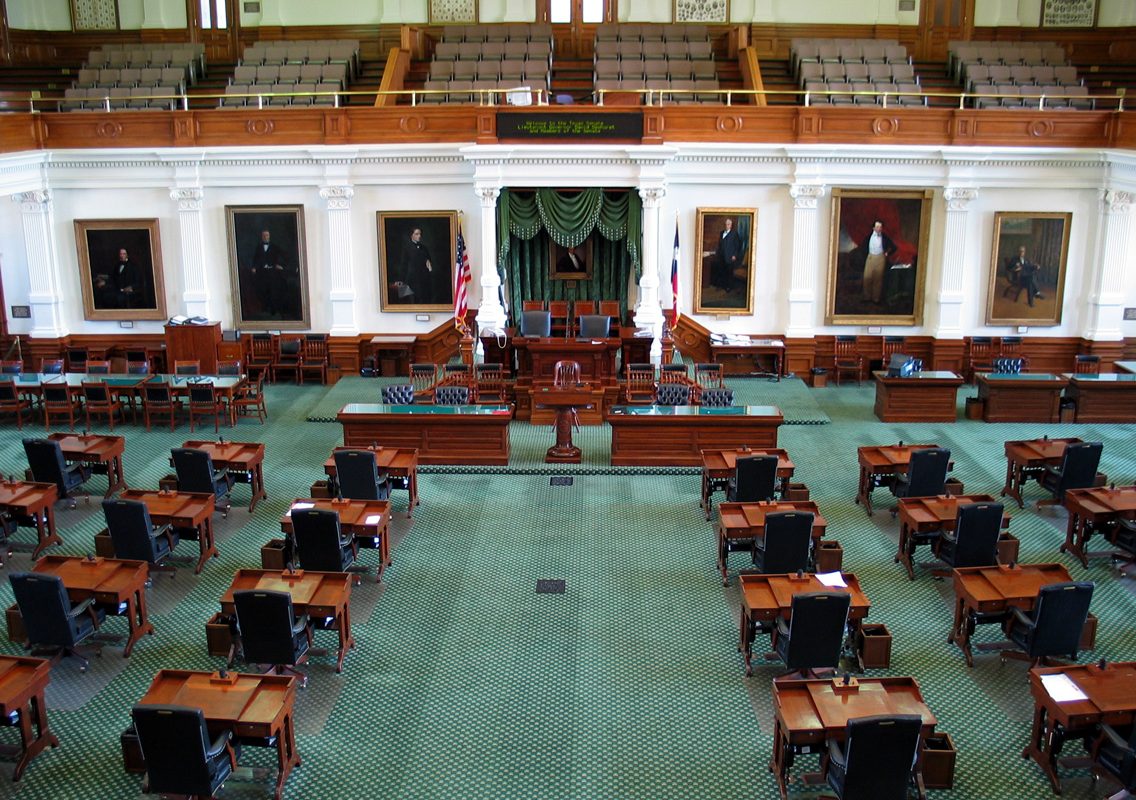

Many Texans learned a new word this year: quorum. And, no, it’s not the collective noun for a group of opossums. A quorum is the minimum number of assembly members that must be present in order to conduct business. For the Texas House of Representatives, that minimum is two-thirds of its members.

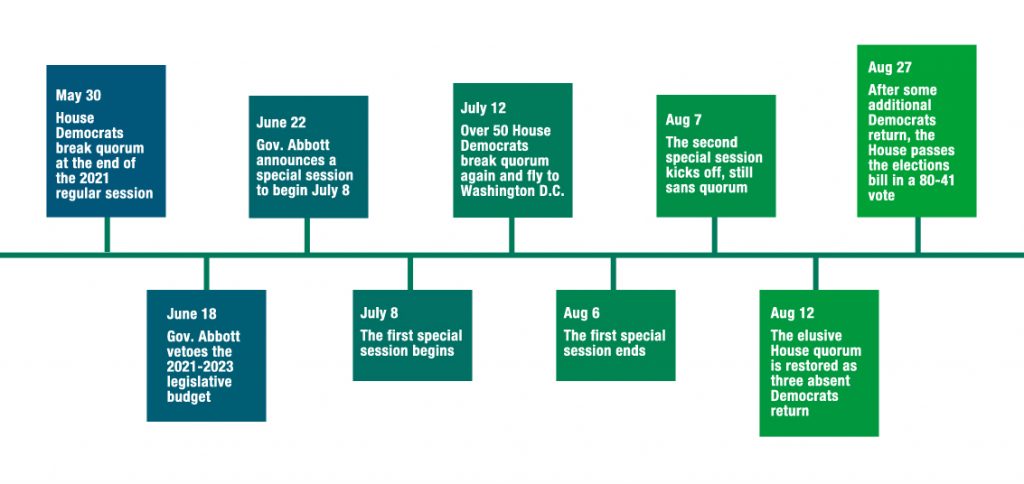

Earlier this summer, House Democrats made national news when they broke quorum (i.e., left the building) during the final hours of the regular legislative session to kill a contentious elections bill that opponents argued was designed to disenfranchise Democratic voters and voters of color. Since then Gov. Greg Abbott has called two special sessions, both of which were shunned by enough Democrats to continue to deny the House a quorum, leaving House Republicans stuck in an eternal return of daily check-ins with no actual work getting done. And then, six weeks into the stalemate, the prodigal Dems returned. Well, at least enough of them to secure a quorum and ultimately pass a bill similar to the one that sparked the initial walk out.

If you’re struggling to understand what is going on in Texas politics lately, you’re not alone. I spoke to Jim Henson, director of the Texas Politics Project at The University of Texas at Austin, to answer some burning questions.

Are special sessions normal?

Texas itself is unusual in that it’s a large and populous state with a legislature that meets only every other year. To deal with issues that might come up in between regular sessions, the Texas constitution allows the governor to call special sessions (limit 30 days each) “at any time and for any reason.” They’re also used to revisit legislation that didn’t make it through the previous session, as with this year’s elections bill. And, unlike regular sessions, special session agendas are set solely by the governor.

“These have always been a mixture of what we might think of as emergency response but also agenda management by governors and the political leadership of the state,” says Henson.

This isn’t Abbott’s first special session, nor is it the first time multiple special sessions have been called back to back.

What about the quorum break?

So, yeah, breaking quorum is far less common though not unprecedented. The last time something like this happened in Texas was in 2003, when Democrats fled to Oklahoma and New Mexico to thwart a Republican redistricting plan. It ended up being passed later that year in, you guessed it, a special session.

The quorum break is a strategy of last resort for a minority party and in the case of the Texas House – which, unlike the Texas Senate, doesn’t allow filibustering – was their only remaining card to play. But whereas a filibuster delays voting on a particular bill and can be used to run out the clock on a session (perhaps most famously by Sen. Wendy Davis to block an abortion bill during a 2013 special session), a quorum break pretty much shuts down the entire chamber. Several other bills died along with the elections bill when voting could not proceed during regular session. Abbott’s current special session agenda includes more than a dozen other items (including a few that Democrats would likely support), all of which were stalled until the recent restoring of quorum.

Anything else strange about this year?

Abbott’s line-item veto of the 2021-23 Legislative budget is certainly an anomaly. Vetoing only one section of a bill is not unprecedented but doing so to defund an entire branch of the state government as punishment for a walk out is a new and drastic tack.

“But it fits into a pattern which we’ve seen with this governor, and frankly with his predecessor,” say Henson. “In which there’s been a sustained effort to strengthen the executive branch within the Texas political system. That is bound to come to some degree at the expense of the legislature.”

Wait, hang on, so legislators won’t get paid unless they pass a new budget during a special session?

Interestingly, the legislators’ (rather small) salaries would be unaffected because they are guaranteed in the state constitution. It’s staff salaries that are/were threatened by Abbott’s veto, which is more problematic because those folks are essential to the functioning of the legislative branch and, unlike many of the legislators, generally don’t have additional sources of income.

The governor’s move was designed to increase pressure on Democrats to return but had the potential to hurt both parties, Henson explains, “This was a blunt force blow against the Legislature that he justified as punishment for Democrats not doing their job but which falls on all legislative offices. It’s particularly important given that this is a redistricting year. That put pressure not only on Democrats but also on Republicans to resolve this in some way because they [Republicans] are very interested in getting redistricting done because they’re going to dominate the process.”

What about that third branch of government I learned about in high school? Judicial?

Texas judges have been asked to weigh in on several points, including whether Abbott’s veto should be struck down as unconstitutional and if Texas law enforcement could carry out civil arrest warrants signed by House Speaker Dade Phelan to round up the missing Democrats. And here’s where another quirk of Texas politics comes into play – we’re one of a handful of U.S. states in which judges are chosen by partisan elections (as opposed to non-partisan elections or appointments), meaning that our judges not only run for office, but they run under a party affiliation. It’s not difficult to see how this might undermine the impartiality that is supposed to be the hallmark of the judicial branch.

“At the moment, we are seeing a broad tendency for democratically elected judges mostly at the local and district level to be more sympathetic to Democratic arguments and for the Republican incumbents, particularly in the executive branch, to be relying on a Republican dominated Supreme Court to serve as something of a back stop,” Henson explains.

You can observe an analogous story playing out in the state’s battle over mask mandates. City and county level mask mandates issued in opposition to Abbott’s state-level bans on such orders have been temporarily upheld by local judges only to be struck down later by the state Supreme Court.

“This inflamed partisan fighting that’s consuming the legislative and executive branches has now, somewhat inevitably, spread into the judicial branch,” says Henson. “While nobody would say that there’s no partisanship in the federal judicial branch, the partisanship is very upfront and deeply built into the system of popularly elected judges in Texas.”

Did the quorum breaks do anything other than delay the inevitable?

Perhaps. The initial quorum break at the end of the regular session did result in halting the passage of an elections bill that had many last-minute additions tacked onto it and in shedding light on their specifics. In the aftermath, two of the more troubling items were removed from the current bill (restricting Sunday morning voting and making it easier for judges to overturn election results over claims of fraud).

The Democrats also made an interesting move when they broke quorum at the start of the first special session in July by traveling to Washington D.C. in an attempt to draw national attention to the situation in Texas and to promote federal legislation aimed at protecting voting rights. But whether that will pay off in terms of said legislation actually being passed remains to be seen.

“We haven’t really settled the check on whether this is going to work or not,” says Henson. “They undoubtedly gained more attention for the issue and more media coverage in the short and medium term but it’s a very difficult media environment and there’s a lot competing out there particularly, well, pick your week. It’s been a very crowded media environment and a very tough political summer in the United States and in Texas.”

Henson also points out that another possible benefit to individual legislators could be an increase in name recognition that could help them in any future campaigns outside of their current districts. “Democrats with statewide name recognition are few and far between,” he says.

So, is everything back to normal now that the House has a quorum again?

“When you engage in something that’s this disruptive to the regular order of business in the legislature, it has a lot of unintended consequences and we’re still waiting to see those,” says Henson, referring to the quorum breaks. “An important one would be how it affects the relationships among the legislators in the House. There’s been a lot of tension between the House and the Senate and this additional tension inside the House probably plays to the advantage of the Senate and the lieutenant governor to some degree.”

Additionally, the return to quorum wasn’t a unanimously agreed upon strategy among House Democrats. Several members who did not return have publicly voiced disapproval for what they feel amounts to abandoning the cause.

We’ve also already seen some legislation aimed at preventing what happened this year from happening in the future. Texas Senate Republicans have proposed to amend the state constitution to change the quorum threshold from two-thirds of a chamber to a simple majority. And one senator introduced a (mostly symbolic) bill to remove the governor’s line item veto power.

“Big political fights never take place in a vacuum and there are always moves and countermoves. We’re seeing a lot of fights over fundamental rules and processes,” Henson notes. “These are not just policy fights, these are institutional fights as well.”

Do Texas voters even want any of the changes in the current elections bill?

Henson and his colleagues at the Texas Politics Project conduct regular public opinion polls on a variety of issues in state politics. On the subject of the current proposed changes to Texas elections, a few measures have broad public support (for example, ensuring that voting machines are not connected to the internet) but most of what is being proposed is considerably more popular among Republican than Democratic voters. This isn’t particularly surprising as Americans no longer seem to live in a shared reality on many matters, including elections.

“Overall what we see is a lot of polarization in people’s views on voting and elections and how much should be done and what should be done,” says Henson, citing a tendency for Democrats to believe that the threat to fair elections comes from eligible voters being prevented from voting while Republicans are more likely to fret over ineligible voters casting ballots. “There’s a fundamental difference among partisans of what the problem to be solved here might be, if there is a problem. And that shows up in public opinion on the specific items and it also shows up in the balance of things in the proposal that are about increasing turnout versus preventing irregularities and tightening rules.”

Are House Democrats going to break quorum again if things go south during this or future sessions?

Well, despite Ted Cruz’s suggestions, no lawmakers have yet been shackled to their chairs so it remains a possibility.