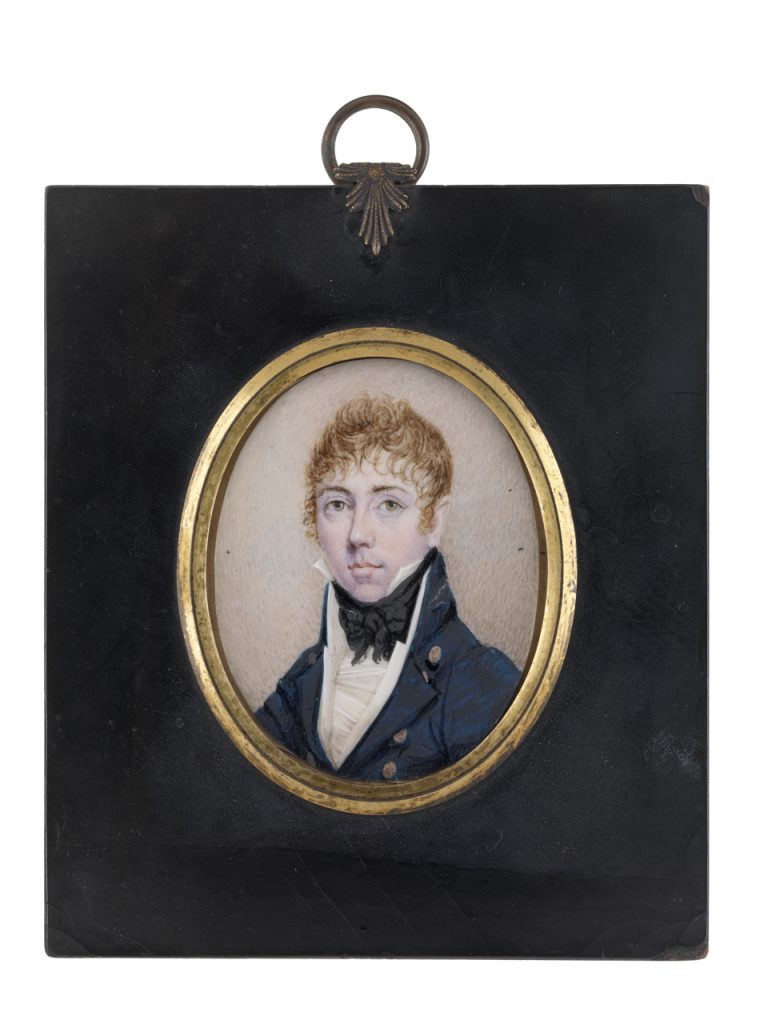

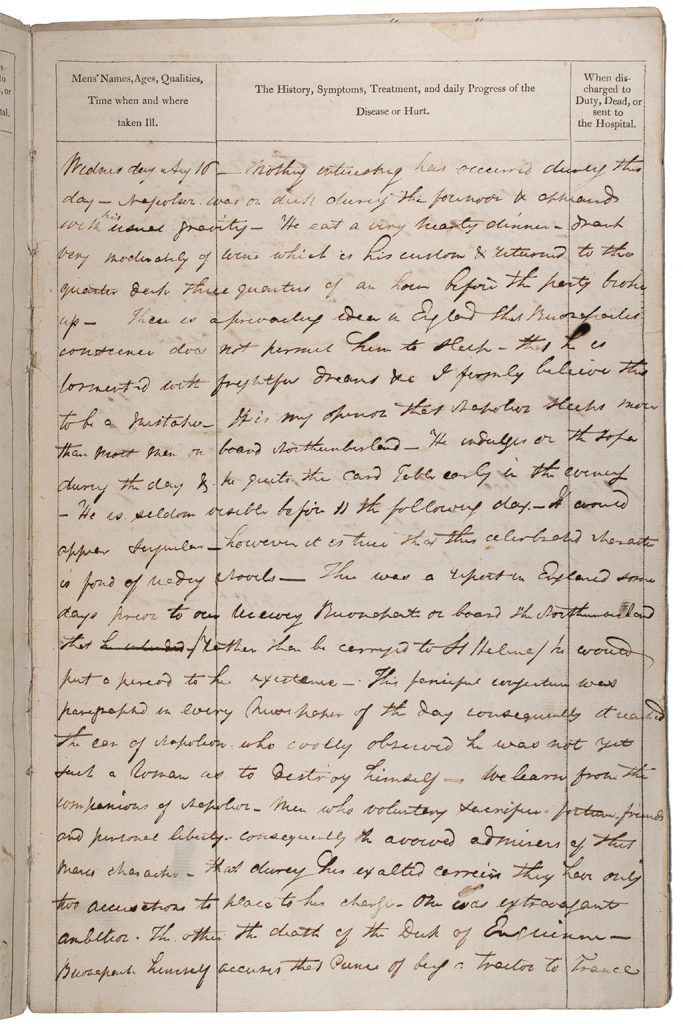

In 1815, William Warden was surgeon of HMS Northumberland as it transported Napoleon Bonaparte to his second (and hopefully final) exile. Well aware that folks back home—or even, possibly, history itself—would be interested, Warden took notes in an old surgeon’s log. This journal now resides at the Harry Ransom Center. It includes his daily observations of and direct conversation with the Corsican Ogre, the Great, the Nightmare of Europe, Napoleon Bonaparte himself. Supposedly.

On return to England from St. Helena, Warden found himself so pressed by his friends for stories of Napoleon that “I may be said to have been in a state of persecution from the curiosity which prevails respecting that extraordinary character.” Stories taken from the notes in his journal filled the letters sent to his future wife, Elizabeth Hutt. Having no experience in publishing himself and expecting to soon be sent away on active duty, Warden collected the letters and put them in the hands of a “literary gentleman” for publication. Once in print, his stories about Napoleon set a scandal in motion.

The introduction of Warden’s book, Letters from St. Helena, assures his readers “That every fact related in them is true; and the purport of every conversation correct—It will not, I trust, be thought necessary for me to say more—and the justice I owe to myself will not allow me to say less.” It claims authenticity and first-hand experience as a selling point. And the claim worked. The book, “owing to the intrinsic interest of the subject, ran through five editions in as many months.”

The Quarterly Review, though, was not a fan, savaging both Warden and his book: it was “founded in falsehood” and had the potential to “poison the sources of history.” The book’s “falsehoods and flatteries” of Napoleon threatened to “obliterate from the minds of Englishmen the atrocities with which he had for twenty years ensanguined and desolated the civilized world.” The review describes several factual errors, which range from narrative quibbles and the naïve repetition of the lies of others to severe factual errors. The Quarterly’s first accusation, sure to “astound our readers, and, perhaps, decide the affair,” notes that in the book the “letters” are undated and without longitude and latitude. This, the review assumes, is to disguise the impossibility of some of the events, most notably the repetition by Napoleon of “an infamous imputation” against Sir Robert Wilson contained details impossible for Napoloen (or Warden) to have learned about at the time the letter was supposedly written. At best, the Review saw Warden as a dupe who “brought to England a few sheets of notes gleaned for the most part from the conversation of his better-informed fellow-officers, and that he applied to some manufacturer of correspondence in London to spin them out into” his book.

The Edinburgh Review, on the other hand, admired Warden’s impartiality. It asserted the book was “one of the few works on Napoleon, that is neither sullied by adulation nor disgraced by scurrility; neither disfigured by blind admiration of his defects, nor polluted by a base and malignant anxiety to blacken and defame a fallen man.” Faults in the narrative were blamed on both Warden’s unpracticed French and the inexactitude of working from memory.

News of the book traveled all the way to St. Helena. In a letter to the secretary of war, the man who oversaw Napoleon’s exile reported that Napoleon denied saying anything like what Warden had recorded. The letter also noted that Warden’s publication of commentary on the conduct and character of fellow officers constituted a breach of discipline. Such a breach warranted striking him from the list of surgeons.

So, Warden lost his job. Temporarily, at least.

Napoléon at Fontainebleau, 31 March 1814, painted in 1840 by Paul Delaroche, public domain, Wikimedia commons.

The case against Warden was not very clear. How much of the book, after all, was actually Warden’s work? Much of the blame fell on the mysterious “literary gentleman” into whose hands Warden placed the letters. Another figure held responsible was the Count de las Cases, a member of Napoleon’s suite, later author of a fawning and untrustworthy biography of Napoleon, and Warden’s frequent interlocutor and presumed interpreter. Las Cases had, at best, limited English—to match Warden’s apparently limited French. Warden’s powerful patron, Sir George Cockburn, also certainly factored into his ultimate return to the Admiralty’s good graces.

Yet the lack of certainty about Warden’s responsibility for the book both pardoned and condemned him. The scandal dominates—and appears to justify—Warden’s entry in the Dictionary of National Biography, only to ultimately be dismissed by its author: “There is no reason to doubt Warden’s good faith, but his work has small historical value, for it is merely the ‘literary gentleman’s’ version of Warden’s recollection of what an ignorant and dishonest interpreter described Bonaparte as saying.”

The journal at the Ransom Center offers tantalizing clues to Warden and his book, shedding some light on the question of how much of the content was Warden’s. Despite the fact that letters intervene between book and journal, much of the published book’s text is remarkably faithful to what we find in the journal. But since the journal is not complete, no full assessment of what might have been altered by the “literary gentleman” can be made. What the printed work does lack, though, are some of the journal’s harsher critiques of Napoleon and some details perhaps too lurid to write in letters to one’s future wife.

In one instance, the book greatly softens an anecdote in which Napoleon and his suite observed a group of well-dressed women surrounding the Bellerophon (to catch a glimpse of Napoleon) while they remained at Plymouth. The daughter of General Brown “is said to have fixed his exclusive attention, while she was in a situation to remain an object whose features could be distinguished.”

In the journal, the anecdote is considerably longer—and less romantic. Napoleon asks if the people surrounding the ship are shopkeepers. (The journal recalls that Napoleon “often called us a nation of shopkeepers.”) Later, it goes on: “Bony [i.e. Bonaparte] remarked one young lady in a most particular manner, a daughter of General Brown—he kept his eyes fixed on her for half an hour […] Bony remarked that he never beheld women with such beautiful bosoms—This he most particularly admired and I firmly believe he would anxiously have kissed many who were there…”

More generally, the Quarterly Review’s objection that the book is too fawning does not hold for the journal. At one point, Warden offers the observation that “no woman will fall in love with Napoleon while his hat is off—he has very little the appearance of a gentleman when uncovered.” In the journal, Warden also condemns the French character as “insufferably vain” and says of the French officers aboard: “Their Gasconadry is a tissue of arrogance and falsehood—but I really think they talk in this childish manner that they actually /often a time/ [slashes original] believe their story to be truth.” If there is naiveté to be found in Warden, as suggested by the Quarterly Review, it seems to lie primarily in the act of publishing in a contentious political atmosphere.

As for observations of the character of his fellow officers, little exists in the journal except praise of Admiral Cockburn’s virtuous exploits. Not unlike Las Cases, Warden would later go on to attempt to write a biography of his powerful patron. This became his second, much safer, foray into publishing.

As Stuart Semmel has argued, the predominant sentiment in the British press at the time was one of opposition to and demonization of the current leader of the nation with which they had been so long at war. Napoleon, however, defied easy categorization, and therefore became both a “lens through which to scrutinize the failing of the British government—and a cudgel with which to beat it.” The mixed reception to Warden’s book reflects this conflict. The fact that he was struck from the lists indicates the perils inherent in wading into that battlefield unprepared.

The mode of Warden’s book was a popular one and was perceived to be an important means of understanding and learning from the past as “Anecdotes of the private life of remarkable persons are one of the most amusing and not least valuable departments of history.” Napoleon and the wars that sometimes bear his name were more than political or martial events. Historian David Bell has argued that the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars were the inception of “total war”—the attempt to involve every resource and every person in the realization of a military goal—which heightened their social and cultural impact. Napoleonic battles were spectacles, consumed in newspapers, literature, and as picnic diversions. Many of the major figures of these conflicts became larger-than-life—or, like naval hero Lord Nelson, apotheosized in death.

Warden’s attempt to shed light on the Man of Destiny reflects the complicated relationship of power, popularity, and politics that put Napoleon at the fore of popular culture as both the epitome and antithesis of the spirit of the age.

If the question we ask of Warden’s journal is what new details we can learn about Napoleon, then the answer may be less than we hoped for. The trouble of historical times is precisely the participants’ awareness that the times are historical. This perception complicates the sources produced to record ‘historical times’ both at the time of writing, and in later interpretations, whether those interpretations are concerned with the basic facts in the text, the text itself, its permutations through publication and diffusion, or the author and their intentions. Works like Warden’s were written under the weight of the complicated politics and cultures of their present circumstances, and in anticipation of the future’s certain interest in those circumstances—not to mention the more immediate anticipation of the chance for fame and fortune. None of these factors can be easily dismissed in approaching the text as a historical source.

Perhaps the introduction to Warden’s book was too optimistic in asserting its total truth; perhaps, retrospectively, Warden might feel he ought to have said less.

Julia Stryker is a PhD candidate in history, studying women working at sea in the British Empire. Her interests include gender, labor, seapower, and empire, as well as migration and maritime law, which she is pursuing as a member of the COST network Women on the Move (CA19112). More, including upcoming talks and publications, may be found here.

This was originally published on Not Even Past, a digital magazine founded by academics in the Department of History. This and other articles in Primary Source: History from the Ransom Center Stacks represent an ongoing partnership between Not Even Past and the Harry Ransom Center, a world-renowned humanities research library and museum at The University of Texas at Austin. Visit the Center’s website to learn more about its collections and get involved.