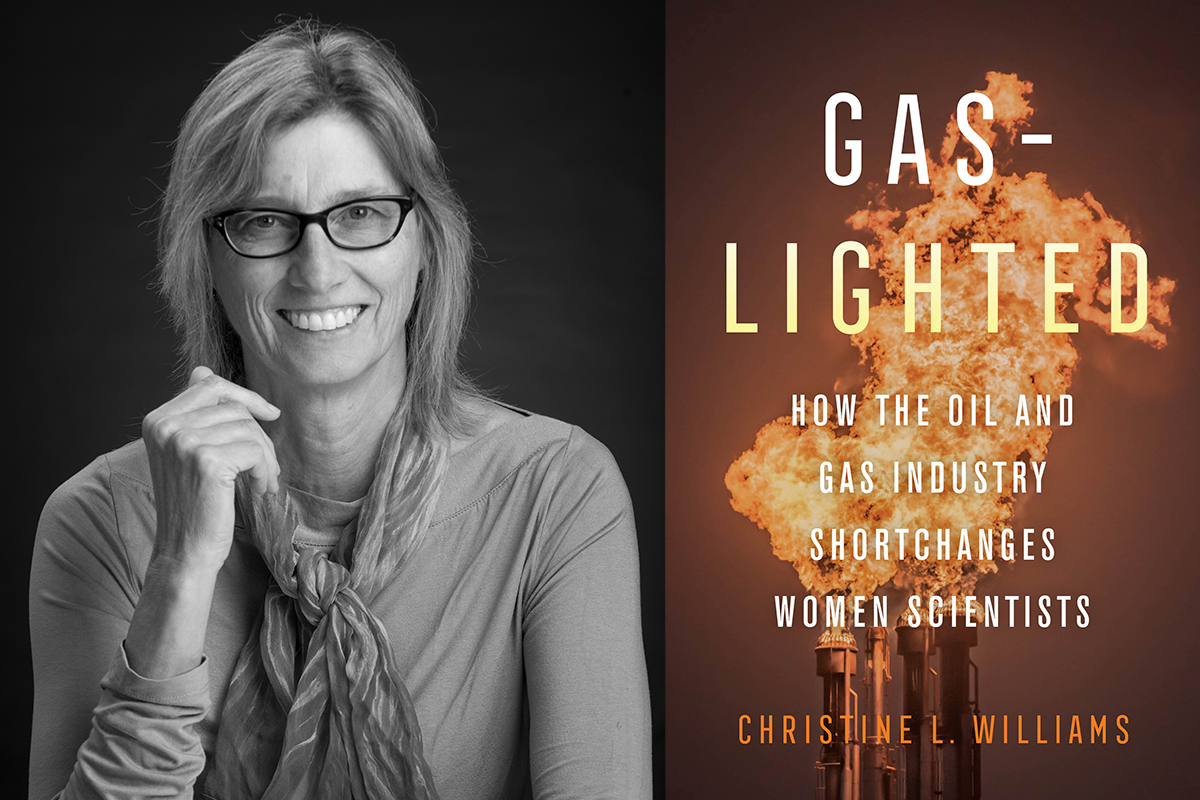

The following is an excerpt from Gaslighted: How the Oil and Gas Industry Shortchanges Women Scientists by Christine L. Williams, professor of sociology at The University of Texas at Austin. The book was published by the University of California Press in October 2021.

After 10 years of researching the question of why the oil and gas industry lags behind virtually all others in measures of gender diversity, I think I now have the answer. Women leave the oil and gas industry because they are forced out.

This answer finally dawned on me in the eighth year of my research, when the price of oil plummeted. As chance would have it, I was studying the industry during one of its periodic down- swings. Oil prices hit a high mark of $110/barrel in 2014. Skyrocketing prices were fueled in part by the “peak oil” hypothesis—the popular belief at the time that world oil production had reached its maximum and would inevitably decline until the earth’s oil supply was exhausted. That very year, the fracking boom started, and mammoth oil reserves were found in the United States. By 2016, the price of oil had fallen to $24/barrel, a 78-percent decline.

In 2016, nearly all of the major companies were laying off workers, including the company I studied. Hiring and firing in this industry track the price of oil: when oil prices are high, the industry goes on a hiring spree, offers signing bonuses, and implements retention and career development programs. When the price of oil drops, layoffs occur, assets are sold, and companies close down or position themselves for acquisition.

Layoffs differentially impact women of all races, as well as racial/ethnic minority men. These groups seem to be targeted by employers when companies downsize.

Christine Williams, Gaslighted

Layoffs are becoming increasingly common in many industries, not only in oil and gas. In the United States, companies face virtually no restrictions on laying off employees. The only federal law restricting employers is the Worker Adjustment and Retraining Notification Act, otherwise known as the WARN Act, which requires large companies to give advanced notice to employees about impending layoffs. Without any other laws to restrain them, major corporations in the United States routinely lay off workers during economic downturns; they also do so when economic conditions are good in order to strengthen stock prices and boost profits.

Layoffs differentially impact women of all races, as well as racial/ethnic minority men. These groups seem to be targeted by employers when companies downsize. In her study of over 800 US companies, economic sociologist Alexandra Kalev found that downsizing can increase the percentage of white male managers as much as 10 percent, while decreasing the percentage of white women and men and women of color by 22 and 17 percent, respectively.

The oil and gas industry is notorious in this regard. Following one company over a cycle of boom-and-bust enabled me to observe the impact of the downturn on geoscientists in the industry. Both men and women were losing their jobs, but women were bearing the brunt of the layoffs. Consistent with the national trends, a third of the men and half of the women exited the company over the course of this study. After years of education policy and diversity campaigns encouraging women to pursue scientific careers, the industry was kicking them out.

In Gaslighted I explore what this employment instability looks like from the points of view of scientists in the oil industry. I collected their personal narratives over the period of boom-and-bust for insight into the organizational processes that produce this gendered trend. The survey data reveal that layoffs affected men and women differently, but the interviews help us to understand the organizational forces that generated this out-come, as well as to explain what downsizing felt like for the people going through it. I talked with women geoscientists over the course of three years to understand how their company squeezed them out.

Women geoscientists in the oil and gas industry make up a tiny number of elite professionals. They are privileged on every dimension—race, education, income—except for gender. But despite their rarity, I believe that their experiences can illuminate why equality in the corporate world remains an elusive goal. An industry that only admits women who are white, and then targets them for layoffs, will not make progress achieving diversity. In the cyclical oil and gas industry, disproportionately laying off the women means that companies can revert to virtu- ally all-white male bastions after every downturn. As layoffs become an ever more accepted and normal business practice throughout the economy, this form of discrimination will spread unless new rules are implemented to prevent it.

To reach this conclusion, I have used almost every tool in the sociologists’ toolbox. I conducted almost one hundred in-depth interviews. Working with my colleague Chandra Muller, I helped design and administer a longitudinal survey of the multi- national oil and gas company that we call “GOG,” or Global Oil and Gas (not its real name). I attended conferences and networking events around the country. I visited geoscientists at work in some of the world’s largest oil and gas companies. I have been an invited speaker at the industry-sponsored Women’s Global Leadership Conference, and at the professional meetings of petroleum geologists and geophysicists, where I have shared my findings and received feedback along the way.

After years of education policy and diversity campaigns encouraging women to pursue scientific careers, the industry was kicking them out.

Christine Williams, Gaslighted

Looking back at my work over the decade, it fascinates me that the answer to the question “Where are the women?” eluded me. Why couldn’t I see what was plainly in front of me from the very beginning? From my vantage point today, I feel like I was gaslighted.

Gaslighting is usually understood to be a form of psychological manipulation and emotional abuse in intimate relationships. The term comes from the name of a classic film in which a man convinces his wife to question reality and her own sanity. In this book, I argue that organizations can also engage in gaslighting. Organizational gaslighting is when companies intentionally deny the facts and blame others for the problems they generate. Corporations attempt to puff up their own image while denying evidence of their malfeasance, enabling them to escape culpability for the systemic inequalities they produce. For instance, they commonly use these tactics to make it appear that they support diversity:

• State a commitment to diversity in their mission statements

• Feature images of men and women from different racial/ ethnic backgrounds in publicity and advertisements

• Donate money to organizations or programs promoting equality that do not interfere with or challenge their normal business operations

• Implement diversity programs, such as unconscious bias training, that do not alter the composition of the workforce

The white male–dominated oil and gas industry does all of these things. Companies claim that they value diversity, but the employment policies they implement to achieve greater diversity do not disrupt the systemic sexism and racism, and other forms of social inequality, that are built into their organizations. Instead, they attempt to throw critics off the scent. This is the essence of organizational gaslighting. One of the goals of this book is to understand why I was misled and to encourage others to recognize organizational gaslighting when it happens to them.

I am now convinced that women do not leave high-paying professional careers unless they are forced out.

Christine Williams, Gaslighted

In the early stages of this project, I spent my time looking for nuanced and subtle processes that reproduced the white male domination of the industry. I focused on how annual evaluations, promotion criteria, and organizational charts favored these men and qualities associated with elite masculinity. I also explored the ways in which women might be holding themselves back. This study overlapped with “Lean In,” a popular corporate- sponsored leadership program that encourages women to over-come their internalized sexism. Thus, I wondered: Were women less motivated than men? Did they hold themselves back from pursuing management positions? Did their ambitions at work collide with their desired level of engagement in family life?

These are all important factors for understanding male-dominated industries. But these subtle processes are not what drive women away. I am now convinced that women do not leave high-paying professional careers unless they are forced out.

Christine L. Williams is Professor of Sociology and the Elsie and Stanley E. (Skinny) Adams, Sr. Centennial Professor in Liberal Arts. She received her Ph.D. in sociology from the University of California, Berkeley. Her research focuses on gender, race, and class inequality in the workplace. Williams is the recipient of the American Sociological Association’s Jessie Bernard Award, a lifetime achievement award “in recognition of scholarly work that has enlarged the horizons of sociology to encompass fully the role of women in society.”