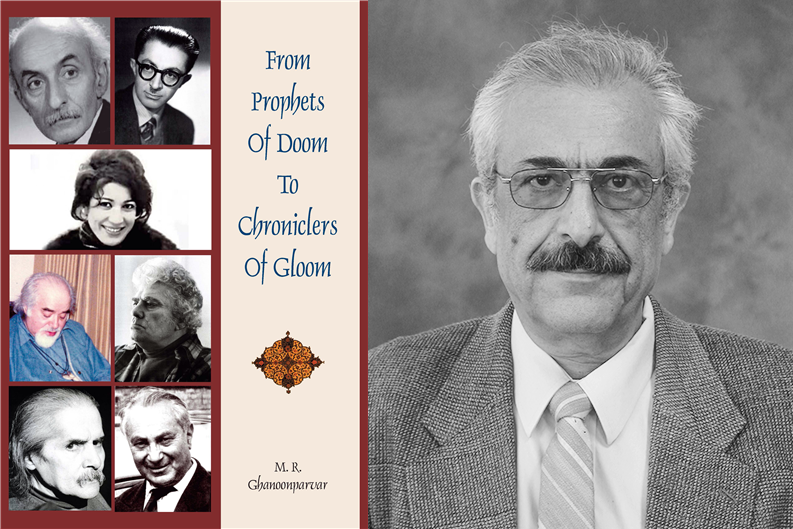

The following is an excerpt of From Prophets of Doom to Chroniclers of Gloom by M.R. Ghanoonparvar, professor emeritus of Middle Eastern studies at The University of Texas at Austin. The book is an examination of modern Persian literature from its inception in the first decade of the 20th century to the present from a variety of perspectives, including within the context of the sociopolitical events and upheavals in the past 120 years as well as the developments and changes in Persian poetry, prose fiction and drama. It was published in 2021 by Mazda Publishers.

Much of the post-revolution fiction of Iranian authors presents the reader with often confused and desperate characters who live in an unstable world and express, as it were, a sense of urgency and focus on the present rather than the future.

This sense of urgency and here and now is especially evident in the work of the war veteran writers. Ahmad Dehqan’s best-selling novel, Journey to Heading 270 Degrees, for instance, is a long, present-tense, first-person narrative of a teenage veteran, Naser, who has not yet finished high school but returns to the warfront to fight out of a sense of camaraderie with his peers.

Like many of his peers, Naser is a volunteer who, motivated partly by a sense of patriotism, has been dispatched to the frontline after only a short period of military training. As he is part of an infantry unit facing the firepower of the Iraqi artillery, throughout the entire story, Naser’s narrative conveys the sense of urgency as he desperately reports on the doomsday scenes and events around him:

Asghar points at the next foxhole. I crawl over to it. There is a gaping crater where the opening was. Lacking the nerve to raise my head and look down into the hole, I see Mehdi in my mind: his fine hair and brown beard shining in the sunlight. I crane my neck and see Mehdi squatting in the hole. His head has flopped to one side over his shoulder. There is a hole on the right side of his forehead. Blood has tracked its way down into his collar. I throw myself into the foxhole. His mouth is filled with white discolored by bits of dirt. The bubbles seem to be increasing; he could be alive!

I place my hand near his mouth. He is breathing. I wipe his lips clean with my fingers. His pupils seem to focus on me. I say, “Mehdi…Mehdi.”

I jump up and his eyes lower. He is in a coma. I shout to Asghar.

Asghar appears on the rim of the crater. Begging him to agree I say, “Mehdi’s alive!”

He only looks at me. Mehdi is certainly alive; he is breathing. But his brains are showing through the hole in his forehead. Bending so far down that his head rests on a sandbag Asghar says, “Nothing can be done for him.”

Foam gathers again around Mehdi’s mouth. I cradle his head in my hands so that he is looking at me. I stare down at him, my eyes fixed on his. There is a strange look on his face as though he is observing me from far, far away. I gently lean his head against the side of the foxhole and wipe my bloody hands on my pants. I jump out of the hole. A horsefly lands on the pool of Mehdi’s blood.

The sense of urgency and desperation is expressed by the fast-paced rhythm of the narrative in present tense, which provides the reader with a vivid, realistic account of what the narrator sees, experiences, and feels.

The technique Dehqan uses in his novel is also precisely the technique used by Mohammad Reza Bayrami in another war novel, Eagles of Hill 60. Even though the teenage narrator in this story is often preoccupied with a pair of eagles and their chick that he comes across in the middle of the war, still danger lurks behind every bush and in every valley and every upslope and downslope on the desolate plains and in the desert, which are full of landmines and artillery shells. Like Dehqan’s Journey to Heading 270 Degrees, Bayrami’s fast-paced narrative in present tense conveys a similar sense of urgency, as the narrator frantically reports on another doomsday scene in which he is caught. While looking for the eagles, the narrator and his friend are spotted by the enemy and are running for their lives under artillery fire:

By the count of ten, we both get up and start to run as fast as an arrow…

Suddenly, I feel that my relationship with the earth and time has been cut off. I no longer see anything or hear anything. I run, just knowing that I have to run. I have to run, and run some more, run with all my strength. Such running that can bring me back to life from the brink of death. Such running that life depends on it. A curtain of fog is drawn in front of my eyes. I only look ahead of me. We can see a bridge in front of us. We have to cross it and get ourselves to the other side. This side of the bridge means death, and the other side means life. How narrow the bridge is, and how long! I’m afraid that it might not hold up with our heavy steps and might break down. I’m afraid we might lose our balance and fall from up there down into the valley…

Unlike the Pahlavi-era literary artists, who seemingly looked into the future and often predicted doom and gloom, for the writers of these war novels, the future does not seem to exist. They seem to be quite conscious of being the chroniclers of gloom. Habib Ahmadzadeh, another war veteran who has become a writer, appears to be aware of this role, as the title of his novel, Shatranj ba Mashin-e Qiyamat [Chess with the Doomsday Machine] (2007), suggests.

The protagonist of Chess with the Doomsday Machine, who is only identified by his wireless radio code name, is Musa, a young Basij volunteer assigned as a lookout, as the city of Abadan is under siege by the Iraqis. When the Iraqis reportedly acquire a new radar system that enables them to detect the precise source of Iranian artillery fire, Musa is given the assignment to find it. On top of his regular military duties, because a fellow combatant is wounded, he is also burdened with the additional task of delivering food to some displaced people, including a retired oil company engineer living in a dilapidated seven-story building, a good place for spotting the radar that is supposed to be on the enemy side of the river.

All these incidences and encounters prepare the grounds for the ensuing conflicts, especially between Musa and the engineer. In one long argument between the narrator and the engineer on the roof of the building where the soldier is trying to discern the location of the Iraqi radar, the old engineer has been taunting the young soldier about his bossy attitude and complaining about the meagre food rations he has been receiving, in addition to probing him about what Musa is looking for that has caused the engineer to be robbed of his “peace and quiet.”

Even though Musa has been trying to avoid disclosing military information to a civilian that he barely knows, in the end, he gives in:

“Okay, look over there and listen carefully,” I said pointing to the other side of the waterway. “They have a type of machine that is able to locate the precise position of our artillery every time we fire at them and then…” I suddenly clapped my hand[s] together causing him to start. I continued, “…don’t drop the binoculars. We haven’t shelled them for two days now and have been scouring every inch of their territory to find that machine and, God willing, destroy it.”

“And if you don’t find this equipment, this machine?”

“Nothing. Only, whenever the mood strikes them, they can unleash Armageddon on the city.”

“And you?” he asked very thoughtfully.

I said, “Us? We’ll have to sit twiddling our thumbs!”

“So your Excellency is looking for a machine that the Iraqis can use to bring Kingdom Come to the city?”

“Right.”

“How fascinating! You are in search of a Doomsday Machine, then?”

Not only the war veteran writers but also older, more established writers such as Ahmad Mahmud and Esmail Fassih in their postrevolution work no longer look into the future and mostly concentrate on the present. In his 1982 novel, Zamin-e Sukhteh [Scorched Land], Mahmud chronicles the wounds of war and its impact on the city of his birth, Ahvaz, which was one of the main targets of the Iraqi invasion in early 1980.

Mahmud begins his chronicle before the Iraqi invasion, when there are rumors about the imminent invasion of the city by the Iraqi forces, but before long, the city is invaded and the people are desperately trying either to cope with or escape from the city. With the bombing intensifying and the rumors spreading that the Iraqi tanks have reached about ten kilometers from the city, the people begin to prepare themselves to defend their city by building trenches, learning how to use weapons, and making handmade bombs. During the air raids and at night, the narrator tells us, the people are instructed to go to the basements of their homes for safety.

At night, the city becomes dark, like the grave. We have covered the small windows of the basement with blankets to prevent any light from seeping out. We light the kerosene lamp and listen to the radio. The weather is hot. The pot in which our dinner is cooking is on the kerosene burner, and the tea kettle is on the Aladdin heater. The heat from the kerosene burner and the Aladdin heater makes the air in the basement stifling and stuffy. On the first days, we dragged the refrigerator into the basement. We have not had any electricity for two nights. Apparently, they have hit one of the power stations.

Many are killed by the bombings, and the city is in chaos. As the situation worsens, fearing for their lives, many people leave the city for other regions of the country in hopes of finding safety.

They stack up the corpses group by group in ambulances and pickup trucks to take them to the cemetery. The lines in front of the bread bakeries are endless. The lines in front of the gas stations are endless. Arguments in front of the bread bakeries and gas stations wind up in curses, insults, and physical altercations. On the street, cars filled with people are moving one after another, as if linked like a chain. The sound of their horns and the shouts of the people intermingle. Young and old have filled the cars like sardines in a can. The luggage on the luggage racks is sometimes one meter high and is wrapped tightly with ropes. Sacks and bundles are piled on the laps of the passengers up to their chins. Here and there, in between the cars, trucks filled with household furnishings and people slow down the traffic. On the top of carpets, bedding, refrigerators, wardrobes, and beds, the young and the old and little boys and girls sit side by side, holding each other tightly, trying to get out of town.

In contrast to the first-person narrator of Mahmud’s novel, who is intimately invested in his chronicle of the city of Ahvaz and its people under Iraqi bombardment, Jalal Ariyan, the narrator of Esmail Fassih’s 1986 novel, Zemestan-e 62 [Winter of ‘84], can be described as a detached observer, even though, like the narrator of Scorched Land, he is in the same city, Ahvaz, at around the same time.

Like Mahmud’s novel, Winter of ‘84 is populated with a host of characters. In contrast to the characters of Scorched Land, which consist mainly of ordinary lower- and middle-class people, however, the main characters in Winter of ‘84 are mostly from the educated and affluent classes. Jalal is a retired professor who had previously taught at the Iranian Oil Company College in Abadan, and Mansur Farjam has just returned from the United States, where he studied computer science and earned a doctoral degree.

The story begins with the chance meeting of Jalal and Mansur, both intending to go to Ahvaz, for different reasons. Jalal wants to find the son of his family’s gardener, Edris, who has been wounded in the war; and Mansur, whose aged mother lives in the nearby city of Shushtar, has been invited by the Oil Company to establish a computer science training center. Hence, they drive together to Ahvaz in the midst of the air raids and missile attacks on the city of their destination. Once in Ahvaz, Mansur realizes that the Oil Company officials, who seem to be more interested in making revolutionary posters of “death to America” and “war, war until victory” than building the computer science center, have failed even to make hotel reservations for him. Jalal, now feeling protective of his new friend, who having been away from the country for many years is unfamiliar with the new bureaucracy, invites Mansur to stay with him at a friend’s house for a while, since the Oil Company seems to be slow in fulfilling its promise to provide housing for him.

Even though he is accustomed to comfortable Western-style living in Minnesota as a senior computer analyst, he seems to be content when he is eventually provided with a very small room in a small Oil Company apartment, the accommodations of which are far beneath what he is accustomed to, and is looking forward to his project of establishing the computer center. To the narrator, however, Mansur seems out of place, not only in Ahvaz but also in the entire country, which has undergone a revolution and is experiencing a war. He describes the way Mansur is dressed when they visit the grave of the son of Naneh Bushehri, a friend’s servant:

We go to the grave of Naneh Bushehri’s son. We stop and say a prayer. Mansur Farjam is standing next to me. His tall height, his American sports jacket, simple pair of gabardine pants, snow-white turtleneck, sunglasses, and young, aristocratic Italian-Eastern appearance do not fit in a scene of death, crying, and mourning. I mostly picture him driving down Grant Street in St. Paul, Minnesota, in a metallic gray Ford Fairlane, with a blonde girl sitting next to him.

Although the computer center never materializes, Mansur gradually becomes accustomed to his new life, especially with the help of Jalal, who introduces him to his many friends in the city. In the meantime, he becomes interested in how the people of Ahvaz are coping with the conditions of blackouts and the shortages of food and other necessities resulting from the air raids. What seems to fascinate Mansur is the ordinary people’s eagerness to join the “Sacred Defense” forces, even at the cost of losing their lives. He soon meets and becomes infatuated with Laleh, who is in love with and betrothed to Farshad, a young man with little interest in the revolution and the war, who is about to be drafted into military service. Mansur’s fascination with the people’s willingness to sacrifice their lives in the war gradually becomes an obsession. He seems to be searching for something to give meaning to his life, and he thinks, like many young people who volunteer to give their lives, that martyrdom is the answer.

In a conversation with Jalal, who has just learned that Mansur has decided to stay in Ahvaz, even though he knows that starting the computer center is no longer on the agenda, in response to Jalal’s question of whether he has decided to stay and settle down in Ahvaz, Mansur says:

“Yes. I’m going to be here for now.” He then sighs and abruptly asks, “What is the definition of martyr, Jalal?”

“The definition of what…?”

“Martyr…”

“Grab my ears and twist them.”

“I’m serious! Ferdowsi says, ‘We are all willing to be killed/ Rather than give our country to the enemy.’”

“Okay. But this is not the definition of ‘martyr.’”

Mansur, obviously preoccupied with the concept, looks up the definitions of martyr in Webster’s dictionary: A martyr is a person “who voluntarily accepts suffering and even death for refusing to renounce his faith or a tenet” or a person “who sacrifices his life with torment and pain for his faith, or suffers and is tortured for a long time.”

Then, in response to Jalal, who warns him against his risky fascination, Mansur replies: “For all these kids to give up their schooling and lives and go to war and jihad as volunteers must mean something.”

The story ends with Mansur now wanting to go and fight on the battlefront. He decides to help Farshad, whom he resembles in appearance, to escape from the war and leave the country. Thus, he exchanges his passport and American permanent residency card with Farshad’s documents and takes his place in the military, resulting in his being killed in the war soon after. Fassih seems even more cynical than Mahmud as he chooses doom for the protagonist of his novel, Mansur, who, despite having the option of a future by returning to Minnesota, opts for a different fate.

M.R. Ghanoonparvar is Professor Emeritus of Persian and comparative literature at The University of Texas at Austin. He has also taught at the University of Isfahan, the University of Virginia, and the University of Arizona, and was a Rockefeller Fellow at the University of Michigan. He has published widely on Persian literature and culture in both English and Persian.