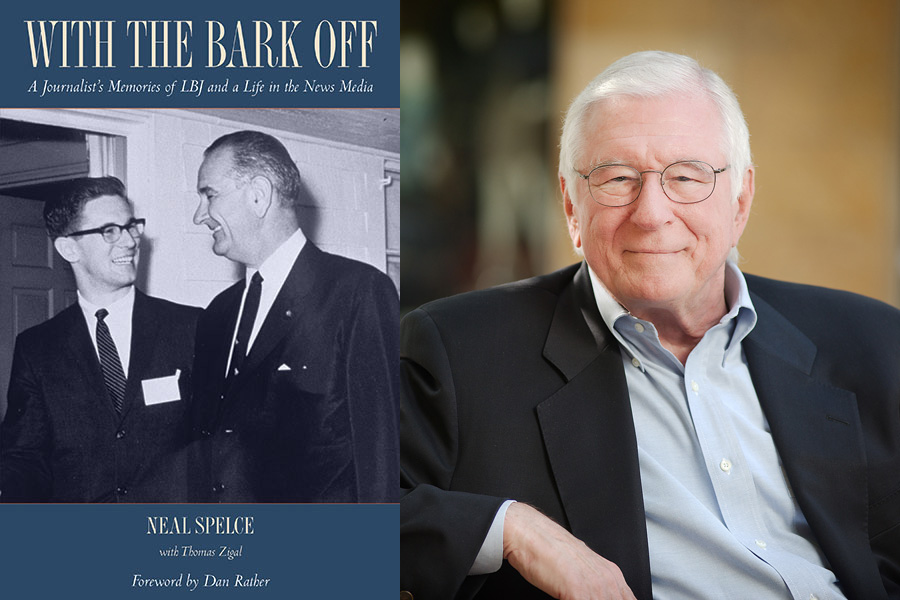

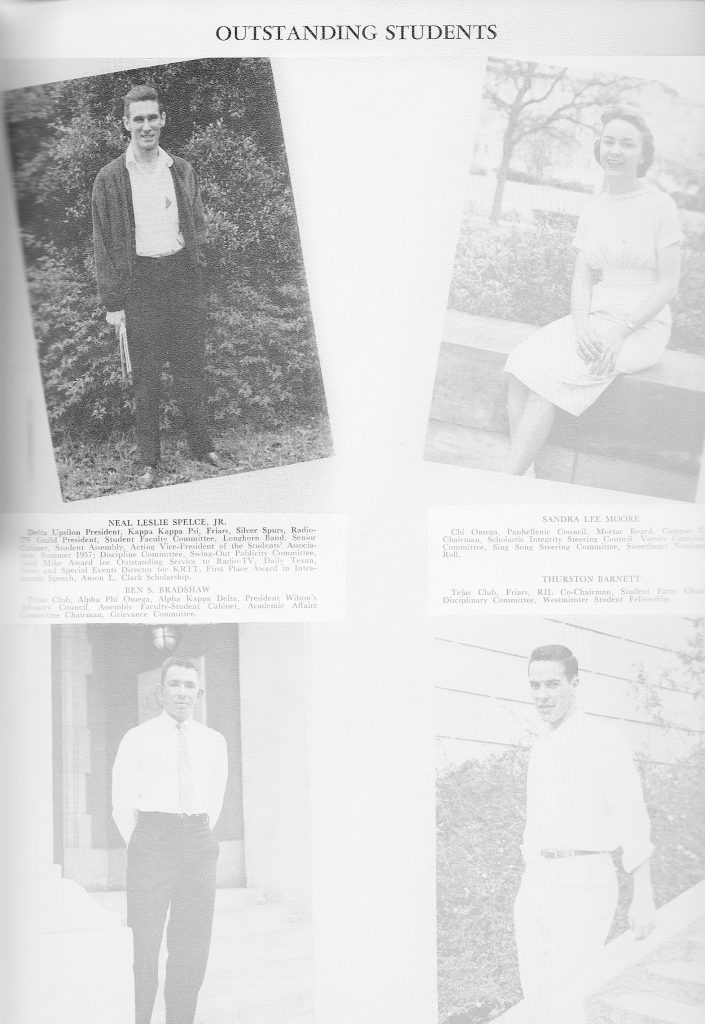

The following is an excerpt of With the Bark Off: A Journalist’s Memories of LBJ and a Life in the News Media by Neal Spelce and Thomas Zigal. Both authors are graduates of the College of Liberal Arts at The University of Texas at Austin, which was still the College of Arts and Sciences when Spelce received his bachelor’s degrees in 1958. Spelce enrolled in the Plan II Honors Program in 1952 as a 16-year-old freshman. The program grounded him for his additional degrees – also received in 1958 – in Journalism and Radio and Television. The book was published in September 2021 by The Dolph Briscoe Center for American History at The University of Texas at Austin.

Both sides Journalism

When Barry Goldwater was running against LBJ in 1964, the Republican presidential nominee booked a campaign stop in Austin, in the heart of LBJ country. Goldwater was a pilot, and he flew his own plane, a fairly large DC-3. We reporters headed out to the old Mueller airport in East Austin, and when Goldwater rolled to a stop on the landing strip, we were out there with our cameras. His supporters were there, too. He pushed open the pilot window and stuck his head out and waved to the crowd. “I’m glad to be here,” he said. “When I took off from Phoenix, they asked me if I’d ever been to Austin and if I knew where it was. I said, ‘No, I’ve never been to Austin, but I’m gonna fly east and when I get to a fairly good-sized city with only one TV tower, I’m going to land.’”

Folks were amazed that I put that on the air because it was “critical of LBJ’s family ownership of the KTBC-TV station.” But I said, “It was a great quote.”

In all the years I was working at KTBC as a reporter and then as news director—making decisions about what stories to air and what not to air—never once did LBJ or the Johnson family give orders to cover this and not that. There were newsworthy events at the LBJ Ranch, and we’d go out there with reporters from all over the nation to cover a prime minister or some other visiting dignitary. That was news. But we were never told “you must come.”

In one case, Walter Jenkins, one of LBJ’s trusted aides, was arrested for a sexual liaison in a men’s room in Washington, DC, and it was a serious scandal. Mrs. Johnson was very supportive of Jenkins, but in spite of her objection, President Johnson accepted the aide’s resignation.

I ran with the Jenkins story on the air, and the next day I received a call from Time magazine. “Spelce, we’re just checking around the country to find out how this Walter Jenkins story was covered. How did you cover it in Austin?”

“We led with it at ten o’clock last night.”

The caller said, “You did?”

“It was the top news story of the day,” I said, “so we led with it.”

They were trying to find out if KTBC had buried the story because it was negative toward LBJ and his family. Our coverage was indicative of how we handled the news at KTBC, even when it wasn’t advantageous to our owner.

That objectivity had been instilled in me by the University of Texas School of Journalism and by Paul Bolton. He was a stickler for getting a story accurate before putting it on the air. Get it first, if at all possible, but get it right, and let people draw their own conclusions based upon what you report. Don’t hide it, don’t dodge it. If it’s out there, it’s out there, and it’s your job as a reporter—as someone who’s conveying important information—to present the facts. The topic doesn’t matter. You want the viewers to say, “Wow, I didn’t know about that.”

Today, there are so many ways for individuals to get news. With the Internet and twenty-four-hour cable news, viewers can go anywhere and find whatever they want to find, with whatever stripe they may want to put on it. But back in the 1950s and 1960s, KTBC was the sole source for television news in Austin and we had a serious obligation to cover it accurately and make sure the facts were correct. I always tell folks, “Don’t rely on a single source. Whenever you’re looking for news, broaden your scope. If you want to watch a left-leaning channel, watch a right-leaning channel as well, so you can balance your judgments and make up your own mind.”

In today’s world, that attitude is considered quaint and out of step with current realities. Sometimes I sound like a Pollyanna, even to myself, but that’s the way I roll.

In my view, polarization is a problem in our society. Most people watch or read to reinforce their own worldviews. And although they’re passionately engaged, they’re missing something if they don’t explore various websites and check other programs and read this blog or that article. I love to go to the online aggregator sites that represent different viewpoints and report on a variety of subjects. I encourage people to get a more complete picture, so whatever their position may be, it’s either reinforced or questioned. It’s important to challenge our assumptions and biases.

Now in my seventh decade as a reporter, I’m often asked, “What do you think about that story that broke today, Neal?” I usually respond, “I was fascinated by it.” Not believing the story, necessarily, but fascinated by the news itself. After so many years in the business, I’ve found a way of standing back and looking at things philosophically.

I’m intrigued by what the left does and what the right does and how everybody reacts to that. I don’t get caught up in “I’m taking his side, and the other side be damned.” I think it goes back to that journalistic training. You’re trained to walk into a situation, whatever it may be—a city council meeting, a public hearing on rising water bills, a school shooting—and analyze what’s going on, what’s newsworthy, what’s most important to your audience. And then you write the story. You don’t get caught up in “Don’t quote this person, but quote this person.” The pursuit of balance and objectivity has carried me forward throughout my long career.

News analysts are everywhere now, but they’re not really that new. I can remember back in the early days when Eric Sevareid would come on CBS as an analyst and commentator. Dan Rather told me one time, “I envision what happens in Eric Sevareid’s life. I can see him waking up, putting on his robe, padding to the front door in his slippers, and picking up several newspapers and reading through them. And then he gets on the phone and says, ‘I think I’ll talk about this today,’ and calls that person and they go have lunch, usually with a martini. And then Eric comes to the office and sits down and writes his piece and records it and goes home. What a life!”

Dan was out there getting punched in the gut, stalked, and shot at, but there’s Sevareid having a martini at lunch.

To be fair to Eric Sevareid, he’d covered the fall of Paris to the Germans in World War II and later parachuted into Burma from a crashing airplane, so he deserved those martinis, because he’d earned his status as a commentator. I watched his analysis over the years, and I’m not sure he ever took a hard right or hard left position. He’d say, “Here is this and here is this, too, and there’s going to be a big battle over this, and we’ll have to watch and wait and see.”

A turning point in polarization may have come with the popular “Point-Counterpoint” segment of 60 Minutes, which aired from 1975 to 1979, a weekly debate between liberal Shana Alexander and conservative James J. Kilpatrick. It was famously satirized on Saturday Night Live, with comedian Dan Aykroyd (Kilpatrick) often replying to Jane Curtin (Alexander), “Jane, you ignorant slut.” I’m not sure if it was the humorous satire or the “Point-Counterpoint” segment itself, but that formula exploded all over country, a harbinger of the future.

Today there are entire teams of folks out there analyzing, pontificating, and arguing “I’m right, you’re wrong.” It’s sometimes entertaining, but usually produces more heat than light.

After I left daily television, I was often brought back to analyze the voter returns during election night coverage. One evening during a statewide race, I was sitting on the set with the anchor and co-anchor, and I had my yellow pad and pencil in front of me. As election returns came in, it was my job to announce that at 7:00 p.m., this candidate was ahead, and at 8:00 p.m., South Texas had not been counted yet and voting in Houston was heavy. That kind of thing. It’s what computers do now, but all I had was a yellow pad and a number two pencil.

The anchor sitting next to me wasn’t the brightest bulb on the porch, and when I said, “We’d better keep an eye on this. The margin is narrowing, and it looks like the other candidate may win,” he said, “Really, Neal? He’s been behind all night long. How can you say something like that?” And I very calmly and quietly said, “Because of the trendline and votes that are still uncounted. South Texas is normally going to go in this direction, and they’re not in yet—and that could put this candidate over the top.”

That’s the kind of pad-and-pencil analysis I did back in the day, and that’s the way I like to watch election returns now. But the computers are so far ahead of everybody, they calculate results down to the minute and report, “We can now declare a winner in the congressional district northeast of Dallas.” Not to mention, “Hey, California and the West Coast, the election is already over and we’ve declared a winner. Your vote is superfluous.”

The Donald Trump election of 2016 is a great example of how analysis can go awry. All the ratings and data showed that Hillary Clinton was going to win. I’d been watching a lot of television coverage, and I stayed up to speed on what was happening. Two or three days before the election, I made the comment, “Trump can win this.” I mentioned that to a pollster who was polling for Trump and the Republicans, and he said, “There’s just no way.” But I insisted, “I don’t think the polls are right.”

I’m not claiming credit for predicting Trump’s victory, but when I was seeing such large, passionate crowds at his rallies, I tried to figure out, “Who the heck are these folks who are so angry and engaged?” And I realized that those folks were not being polled because they were “anti- media” and “anti-polling”—“I’m not going to talk.” Nobody looked at their numbers. But sitting back in my armchair and watching news coverage week after week, I could see what was taking shape. So when I made that “bold prediction,” I was dismissed, but it came to pass.

It’s the job of the reporter to analyze what’s happening with a cold eye to the truth. Polling has become essential, for better or worse, to that highly competitive media world that has emerged over the past thirty years. Unfortunately, the polls sometimes drive public opinion instead of the other way around. I have examined polls, and even conducted polls when I ran my PR firm, and I know that you can direct the results by how you phrase the questions.

When John Connally was running for governor of Texas for the first time in 1962, he was not well known and he was running against a sitting governor, Price Daniel, who was pretty doggone popular. One of Connally’s tactics was to encourage his supporters to vote early. It was a unique idea at that time, and reminiscent of what candidates do today. His campaign would contact the Austin American-Statesman and other newspapers and say, “I understand there are big crowds at the polling places right now, voting early. You ought to send a reporter out there and find out what’s going on.”

Of course, it was a set-up. The reporters would ask the early voters, “Who are you voting for?” and the response was usually, “I’m voting for John Connally.”

Governor Price Daniel’s response was, “My voters can go vote tomorrow.”

But the overall effect was it looked like an enthusiastic groundswell for this unknown candidate named John Connally. The press was being manipulated by his campaign. It wasn’t the first time that a political campaign had outmaneuvered an opponent, and it certainly wouldn’t be the last.

Neal Spelce’s was a legendary news anchor and news director for KTBC-TV in Austin who gained national recognition for his on-the-scene live coverage of the UT Tower Sniper mass murders. He was also a close associate of and spokesperson for President and Mrs. Lyndon Johnson.

Thomas Zigal’s novel Many Rivers to Cross won the 2013 Jesse Jones Award for fiction from the Texas Institute of Letters and the 2013 Best Work of Fiction from the Philosophical Society of Texas.