In the hour before I sat down to start writing this piece, Steven Seegel tweeted four times. The first was a retweet of a thread from Tymofiy Mylovanov, the president of the Kyiv School of Economics and an advisor to Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky. Mylovanov’s 16-part thread is a grim but also defiant argument that both sides in the Ukraine-Russia war are structurally unable to win but also emotionally unwilling to lose. The war, therefore, is likely to drag on for years, and will end, he predicts, only when the U.S. and other Western allies decide to more directly involve themselves in the fight.

Seegel’s next three tweets were recorded re-tweets of other Eastern Europe experts discussing the recent headline that the Russian government has ordered its pedagogical universities to cease teaching all courses in sociology, cultural studies, and political science. “Horrifying,” appends Seegel.

By the end of the day, he’ll likely tweet another 50-500 times. The effect of all this tweeting, RT’ing and QT’ing is a kind of chorus of voices, mostly international scholars and writers, many of them from Ukraine, who are providing in-the-moment interpretation and contextualization of the war and the politics surrounding it. The goal of this chorus, conducted by Seegel, is to provide real-time information on the war for the purpose of open-source service and archiving, and to counter the mis- and disinformation coming from the Russian government, in particular the Putin-authored narrative that Ukraine is merely a sub-unit of Russia, and that the invasion is therefore a war or liberation or reconciliation. In response to the big man’s big lie, Seegel throws back a host of overlapping, truth-telling voices.

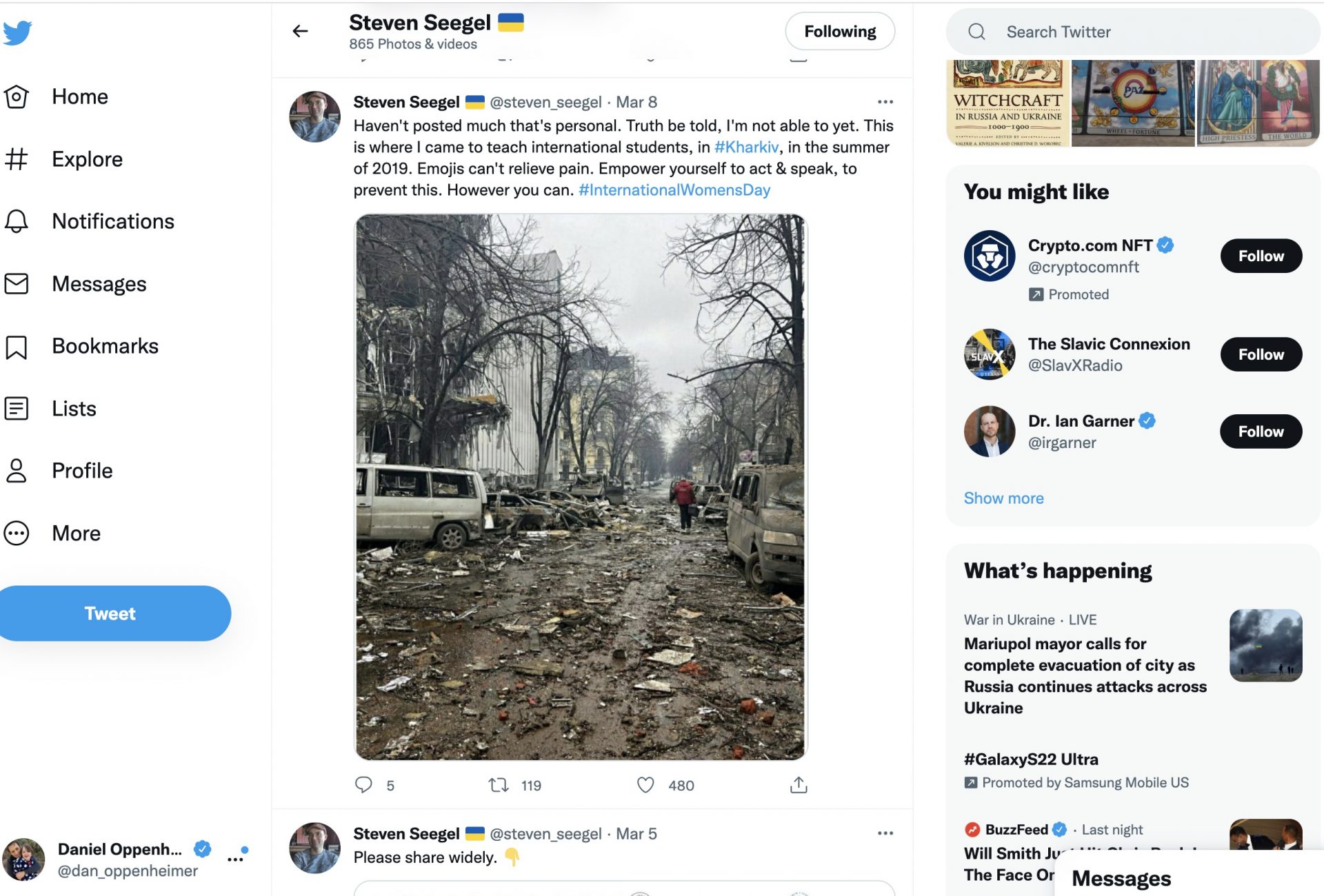

“It’s a strategy of polyphony,” says Seegel, professor of Eurasian and Slavic studies at The University of Texas at Austin. Since the war began, he has tweeted about 12,000 times, in the process adding more than 10,000 followers to an account that was previously focused primarily on maps and on Seegel’s podcasting. He plans to keep going, with the help of international colleagues in the digital humanities, for as long as necessary, in order to build what he’s calling “The February 24th Archive.”

“In the darkness on February 24th, I tried to set a historical tone,” he recently wrote. “I don’t know what was in my mind on Twitter exactly, as I began tweeting. I had a plan to mobilize and connect, by the scholarly hundreds, then by thousands in the streets.”

As he’s settled into the process, says Seegel, certain themes have coalesced. It’s important to emphasize Ukrainian agency, both in the choices of which speakers to highlight on his feed and in the broader sense of viewing the conflict not primarily as a proxy war between the U.S. and Russia but above all as a Ukrainian thing. It’s important to connect what’s happening now to dissident moments and movements in the Soviet and post-Soviet past: “from Prague in 1968, to Polish Solidarity in 1980–81, to the Maidan Revolution of 2013–2014, to the Belarusian women and labor strikes of August 2020,” as well as to other anti-authoritarian movements in the rest of the globe. Perhaps above all, it’s urgent to interpret the Ukrainian struggle with an eye to how one’s choices will influence what sovereign, independent Ukraine means going forward.

In this sense, says Seegel, he is both a scholar, having published for over 20 years as a historian of East European geography and cartography, and an activist. The scholar part of him is contextualizing, trying to set the historical record straight. The activist part is concerned less with accuracy than with indeterminacy. The stories of the past and the present are still taking shape, and the future of Ukraine depends on what shape they take. “The 2010s were an illiberal decade,” he says. “We saw in Hungary, Poland, the United States, and elsewhere the increasing power of ethnic nationalism as a force for organizing society and politics.” He has seen Ukraine take a different, bolder path, and in telling the story of the nation in a particular way, he believes, writers and scholars and citizens and artists can have an influence on Ukraine’s future.

I’m finishing up this draft about seven hours since I started writing, and Seegel has tweeted another 60 or so times. The big stories of the day, to judge by his feed, are the Russian order to stop teaching its citizens about their own society; the death of Russian journalist Oksana Baulina, who was killed in a missile strike in Kyiv; the massive pro-Ukraine rally in Warsaw, Poland; and the Ukrainian military’s push-back in the city of Kherson.

The think-piece of the day is “The Nation Ukraine Has Become,” on the website of the New York Review of Books. It’s by Olesya Khromeychuk, the director of the Ukrainian Institute in London, and Sonya Bilocerkowycz, a Ukrainian-American lecturer in English and creative writing who teaches at SUNY Geneseo. They make the case that we need to see Ukraine as not just another democratic nation worth defending against its authoritarian neighbor, but as the leading edge of democracy in the world.

“Putin,” they write, “uses a retrograde, mythic version of a Russian past not only to oppress Ukrainians, but also to prevent his own people from imagining a future in which their lives are worth more than serving as cannon fodder for his wars. In contrast, Ukrainians have a clear vision of the future for themselves and their country, and they will do everything to protect it. As we watch the news reports about the shelling of hospitals and kindergartens, about babies being born in bomb shelters, we marvel at the resolve and resistance of the Ukrainian people. We should be asking ourselves, whether in London, Paris, New York, or beyond, the question that Kyiv is answering right now: Do we have a democratic future of our own worth fighting for?”