Political scientist Kurt Weyland isn’t precisely an optimist when it comes to the prospects for liberal democracy in the world. He is, however, a sharp critic of what he sees as alarmism.

“When Trump came in, there was a drastic shift in the mood,” said Weyland, professor of government at The University of Texas at Austin. “A lot of, ‘It could happen here,’ a lot of ‘Fascism is coming to America.’ I understood the concern, but it wasn’t justified.”

A longtime scholar of democratization and its discontents, particularly in Latin America and Europe, Weyland’s work over the past few years has focused on explaining in detail why we are not, despite some appearances, in the midst of either a crisis of global democracy or an ascendant wave of illiberal populism.

“If you look at the really big picture, what we’ve seen over time is waves of democracy,” said Weyland. “Democracy advances in bursts and then there is a recession. When these waves are underway, some countries move to democracy that aren’t quite ready for it, in terms of the strength of their institutions, and then lo and behold they backslide.”

Weyland says that we are currently in the backsliding phase of what scholar Samuel Huntington called “Democracy’s Third Wave.” This wave began in the mid-1970s, with the demise of authoritarian governments in Portugal, Greece, and Spain. It crested in the 1990s, with the fall of the Soviet Union and the democratization of countries like South Africa and Kenya in sub-saharan Africa. It then plateaued for a while, and really began receding around 2010.

From this longer-term perspective, says Weyland, the highly visible populist successes of the past six or seven years—the victory of Trump, the continuing consolidation of power by Erdoğan in Turkey, the electoral prowess of Marine Le Pen in France—should be concerning but not terrifying. It feels like something new is going on, but in fact most democracies are persisting. Most that don’t are predictable manifestations of our current phase of democratic recession. And while there are a few outliers, there are always outliers in history.

“The recent fear of populism has gone too far,” he writes in “How Populism Dies: Political Weaknesses of Personalistic Plebiscitarian Leadership,” published last spring in Political Science Quarterly. “Certainly, personalistic leaders seek to establish their unchallenged predominance, which would smother democracy.

But they are far from always succeeding. Instead, many fail. As a result, populism is not nearly as universally damaging to liberal pluralism as it looks in theory.”

Weyland defines populism as a political movement or strategy that is highly dependent on the charismatic leadership of a single figure who acts as a personal embodiment of his (very occasionally her) followers’ hopes. Populist figures tend to run in rhetorical opposition to the elites of a given society, promising to return power to the common folk, and they draw their political and electoral strength from the energies of the masses rather than from the power of political parties or other establishment entities.

What Weyland has found in his research, which looks at the range of populist challenges to European and Latin American democracies since 1985, is that while populist leaders often threaten to erode democracy in various ways, they typically fail to realize those threats. In fact, says Weyland, it is often the same qualities that make populist leaders attractive in the short run—their extreme confidence, their antipathy to elites, and their desire to steamroll bureaucratic structures—that lead to their failure in the medium and long term.

“These movements are all focused on one personality,” says Weyland. “The leader is totally domineering, and the belief is that he incarnates the will of people. But domineering personalism makes populist governance very error prone. It’s really hard for one person to make decisions on such a wide range of things. If they don’t listen much to expertise, if they don’t take advantage of the capacities of the bureaucracies, there is a good likelihood they won’t understand things, and will end up making mistakes.”

In fact it’s much worse than that for these leaders, says Weyland. Because they operate outside of traditional political, legal, and bureaucratic structures, they are not only bad at checking corruption, they are more likely to deploy corrupt means as a means of maintaining power. More corruption leads to worse governmental outcomes and, if publicly exposed, an erosion in mass support. Populists’ hostility to the existing political elites breeds powerful enemies, who often bide their time until the populist leader is vulnerable, at which point they strike back. And overcoming the checks and balances of even flawed democracies is just really hard, particularly when you’ve already compromised your capacity to make good decisions and alienated political elites.

The result, says Weyland, is that even when populists succeed in taking power, as they have in dozens of countries over the last few decades, they tend not to last too long or to inflict much enduring damage to democratic structures. Even in those cases where democracy suffers, it often rebounds after the populist leader is voted or otherwise forced out.

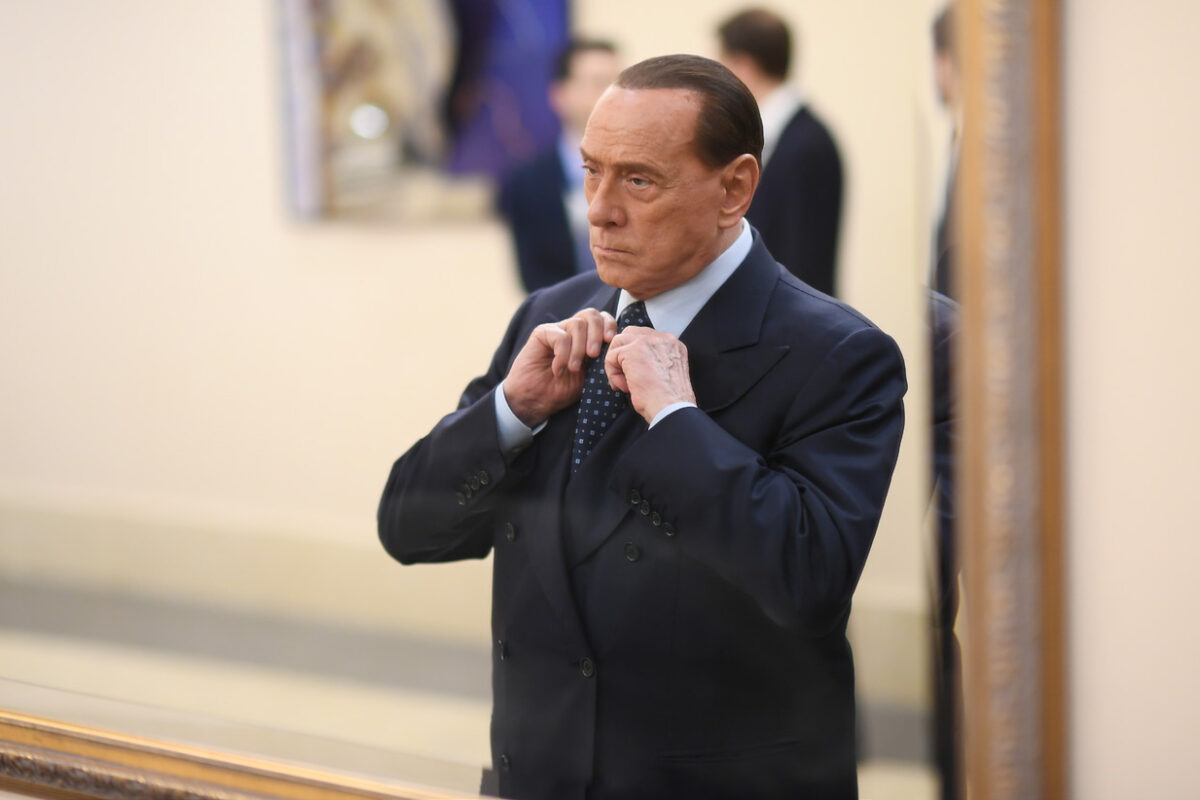

In his recent paper in Political Science Quarterly, Weyland includes a fascinating table that runs down the outcomes for recent populist leaders. It’s a record almost entirely of failure. Silvio Berlusconi in Italy is felled first by the “Quick collapse of [his] coalition.” After a subsequent return to power, he is defeated by “Scandals and precarious coalitions.” In Ecuador, Rafael Correa suffers “Betrayal by handpicked successor.” Robert Fico in Slovakia loses power after “Collusion scandal and mass protests.” And so on.

For Weyland, the occasional populist successes tend to prove the rule. They occur only under very particular conditions. Existing democratic institutions have to be weak, and the populist leaders need to benefit from either a) a huge windfall of oil or gas money, or b) an acute crisis that is resolvable.

Hugo Chávez in Venezuela, for instance, was able to sustain popular support, even as he chipped away at democracy in Venezuala, because the high oil and gas prices of the 2000s enabled him to essentially buy support, generously funding both social programs for the masses and lucrative contracts for business. Alberto Fujimori, who was president of Peru from 1990-2000, resolved two acute crises early in his presidency: he suppressed the Shining Path guerilla insurgency, and he brought down massive hyperinflation through a bold and tough adjustment program.

“No wonder that this populist leader won 80–85% approval when closing Congress and the Courts,” writes Weyland in “Populism’s Threat to Democracy: Comparative Lessons for the United States,” published in Perspectives on Politics in June 2020. “A severe double crisis allowed Fujimori to prove his bold agency, bring drastic relief, and garner the overwhelming popularity required for imposing constitutional change.”

The anti-democratic successes of Chávez and Fujimori were dramatic, but they obscure how many other populists have failed to inflict permanent damage on their countries’ democratic institutions. In the absence of an acute, resolvable crisis or a massive hydrocarbon windfall, most populist, anti-democratic leaders are defeated by democracy, by their enemies, and perhaps above all by complexity. Weyland offers the recent example of COVID-19, which was handled poorly by almost every populist leader in the world.

“Populist leaders can get a lot of mileage out of combatting crises,” he said, “but it only works when crises are resolvable through resolute countermeasures. The coronavirus is very very hard for them, because you can’t simply defeat that damn little virus. Especially when you’re a populist trying to operate in a democracy with rule of law. You can’t get away with locking people down and up, like in China.”

In general, says Weyland, liberal democracies have handled COVID-19 better than populist governments, and although there are some authoritarian states, like China, that have kept their pandemic numbers low, there are plenty of others, like Russia, that haven’t. And it is not China- or Russia-style authoritarianism, in any case, that is the main ideological rival to liberal democracy in today’s world. It is populism, and populism is proving a less compelling rival than many fear. Which is why Weyland is an optimist, sort of.

“Liberal democracy clearly faces a lot of challenges,” said Weyland, “and liberalism is boring and unexciting when you have it. It is not an ideology. It deliberately does not provide a common goal for humanity. That is one of the biggest reasons for the rise of populism. But as I think we’re seeing in Ukraine, liberal democracy can be heroic when it is under threat. It can be exciting when you don’t have it. Also, there isn’t really an alternative, or at least not one that seems able both to inspire people and to meet the challenges of modernity.”