The influential literary journal The Review of Contemporary Fiction once devoted a full issue to essays on the work of only two authors, Zulfikar Ghose and Milan Kundera. In their introduction, the editors noted that “Zulfikar Ghose has both ranked with and outranked several of the best English language writers in England and America” and went on to present him as “a unique figure in contemporary literature,” comparing “his evolution across languages and national boundaries” to that of Conrad, Nabokov, and Beckett.

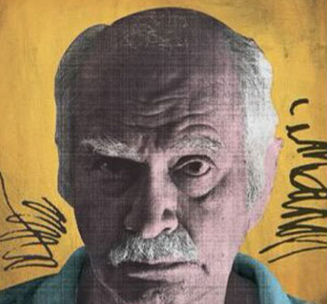

Such praise offers a good example of the extensive critical attention both here and abroad given to the work of UT creative writing professor emeritus Zulfikar Ghose (Zulf to friends), who passed away last summer at the age of 87, unexpectedly for many of us who knew him well because he had always been so valued as a friend that we somehow felt he would always be with us.

*

He was the author of more than twenty-five books and his range was wide: fiction, poetry, and criticism.

As a novelist, he challenged the limits of traditional realism with innovation in structure and language. He was probably best known for his trilogy The Incredible Brazilian (1972-78) in the magical realist vein (the protagonist lives through multiple incarnations and hundreds of years of Brazilian history), yet his writing reached an apex, I’d say, with a trio of novels published in the 1980s, again set in Latin America and perhaps even more powerful in a hauntingly metaphysical way: A New History of Torments, Don Bueno, and Figures of Enchantment. Coming of age at a time before the multicultural or postcolonial tags were affixed to writers, Zulf was nevertheless eventually cited as being the first Pakistani to publish a novel in English with a major UK publisher, The Murder of Aziz Khan (1967); applying a critical eye to the early independent Pakistan, the book was initially banned in some circles there. In later years he was celebrated in Pakistan and visited on several occasions to receive honors, and a national literary prize was given posthumously this fall. His large personal book collection is in the process of being donated to a university library in Lahore.

He had served on the jury for the Neustadt International Prize for Literature, usually considered second in importance only to the Nobel award. I know that when writers and literary critics from other places were in Austin for any reason they often would also make it a point to seek out Zulfikar Ghose.

*

Zulf’s own background was very international: growing up in Bombay (now Mumbai) as a Muslim before the partition, his family originally from Sialkot in Pakistan; living and studying in London after his businessman father decided the family should leave India following the partition, with Zulf at one point working as a traveling cricket correspondent for the London Observer ; spending much time throughout adult life in Rio de Janeiro, the birthplace of his lovely wife, the Brazilian artist Helena de la Fontaine; and coming to the U.S. to begin teaching at UT in 1969, retiring in 2007. He did address the matter of exile and displacement in depth in his novel The Triple Mirror of the Self (1992), though he himself disliked those limiting and perhaps reductive categories of multicultural, postcolonial, etc., used chiefly by academics: he simply wished to be seen as a writer, and in his case, I might emphasize, an extraordinarily gifted and unique one.

As said, in addition to the fiction there were a number of books of both poetry and criticism. He began publishing poetry in London right after university study as a member of a new movement in poetry there called The Group (where he met Sylvia Plath), and his poems are frequently anthologized and studied in classrooms today; the poem “Geography Lesson” alone has dozens of online study guides and analysis pages for students. His books of criticism, including Shakespeare’s Mortal Knowledge, on the tragedies, and The Fiction of Reality, a paradoxically titled examination of modernism/postmodernism and writers such as Woolf, Beckett, and Robbe-Grillet, are not the expected scholarly studies with analysis and commentary based mainly on research, as worthwhile as that type of an approach might be, but are very original literature in themselves, one creative mind interacting in elegant, startlingly insightful prose with those other brilliant creative minds, work that will last. A book-length meditation on Proust is forthcoming.

When I first came to Austin in 1980 to teach creative writing in the English department I was assigned Zulf’s office in Parlin Hall while he was on leave (atop a filing cabinet was a great photo of Zulf and Helena in 1960s London wearing mod attire of the day and standing beside their Lotus Elan sports car, and the shelves were filled with copies of his books translated into many languages), and after he returned to campus we fast became good friends.

There were many weekend dinner get-togethers graciously hosted by Zulf and Helena, with Zulf cooking his culinary specialties (South Asian/Brazilian) at their home in West Lake Hills. His prominent writer friends visiting from throughout the world would often be there, and who knows who you might find yourself with at the table, maybe Angela Carter from England, Wilson Harris from Guyana, or Bapsi Sidhwa from Pakistan, to name just a few of the guests that come to mind. For me the conversation was an education in itself, almost a mini world literature conference. Poet David Wevill—emeritus in our department and, like Zulf, internationally recognized—and his wife Gloria Garza were often there, too, close friends of Zulf and Helena (David and Zulf had known each other since their early days as poets in London), as well as French professor and critic Vanessa Guignery, who lives part of the year in Austin and has written on Zulf’s working as co-author when young on projects with B.S. Johnson, a leading experimental British writer in the 1960s; Vanessa also edited a volume of letters between the two. Preserved at the HRC is Zulf’s decades-long correspondence with his American novelist friend Thomas Berger, author of Little Big Man, adapted for the popular film of the same title starring Dustin Hoffman.

I remember a particularly enjoyable Thanksgiving dinner out at their place on the High Road with several students invited who certainly appreciated the warm hospitality extended while away from home and studying here in Austin.

After his retirement I would sometimes meet on a weekday afternoon with Zulf and David at the West Lake home, good sessions of wine maybe out on the terrace overlooking the pool and much talk of life and literature, the high point of my week. Due to the COVID pandemic of the past couple of years, our friendship was mostly limited to regular emails and phone calls—talk of what we were reading or what we thought of this writer or that, also discussion of the writing we each currently had underway. As a mentor, he generously supported me and many others with our writing, in my case honest to tell me what was good about it and equally honest to say what definitely wasn’t (believe me, that was needed), the input always valued.

Into his eighties, he wrote a regular column on literature for the large-circulation newspaper of record in Pakistan, Dawn, with his last piece, titled “The Force of Originality,” appearing just a month before he died. A stream-of-consciousness semi-autobiographical novel with intensely lyrical language and set in a time in London when young writers were obsessed with T.S. Eliot, Kensington Quartet (actually, that was Eliot’s original title for his Four Quartets), was published in 2020.

*

Personally, Zulf was a considerate and dignified man with a quiet sense of humor who never pursued self-advertisement in this age of rampant self-advertisement, yet maybe chief in his character was how brave he was throughout his career in taking a stand on his literary convictions. And he was firm in his belief that literature, when everything is said and done, maybe doesn’t always have all that much to do with the academic study of it and should essentially and foremost be true art, not just a matter of subject, and only as art can the undeniable and even uncanny magic of language and well-crafted words on the page tap into what is deepest and most humanizing within all of us.

So many do miss him greatly, which sounds like a cliché, I realize, but it is surely true in this case, including his past students, who appreciated him for his inspiring creative writing classes and instilling in them the credo to keep their artistic standards high as young writers and forget the commercial pressures and noisy hype that too often surround much publishing lately. A number of them went on to solid success as writers and continued to correspond and visit with him long after they graduated.

Finally, it might be best to simply add a quote from Zulf himself that appeared in one of his columns for the newspaper Dawn. In the piece he talks of how in interviews, essays, and letters, all great writers seem to express a shared belief:

“Directly or by implication, they refer to their pursuit of art that does not merely convey ideas, but one that glows. And the very few who succeed, produce that gleaming light as an inexpressible aesthetic experience, for which Byron’s ‘glowing India of the soul’ is so illuminatingly suggested that even an unbelieving rationalist accepts it as true.”

And, yes, if there is a good way to describe Zulfikar Ghose’s own writing overall, it is that always and quite wonderfully it glows.

Note: Among the obituaries were those in the newspapers Dawn and The Guardian (where editors have people close to the deceased contribute obituaries of well-known figures).