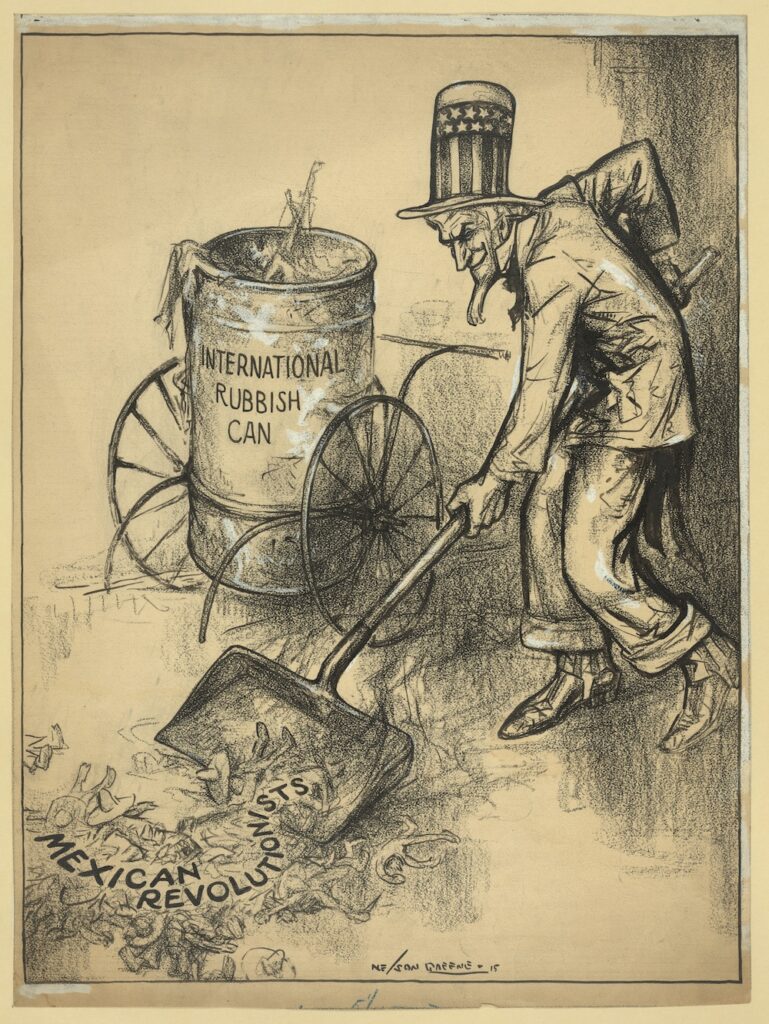

An image near the beginning of Monica Martinez’s book, The Injustice Never Leaves You: Anti-Mexican Violence in Texas, tells a story of visual dehumanization. It’s a 1915 New York Evening Telegram cartoon by Nelson Green depicting a grinning Uncle Sam shoveling a pile of sombrero-wearing “Mexican revolutionists” into a trash receptacle labeled “International Rubbish Can.” It was a nativist take on a complex conflict, the Mexican Revolution, and one that found it convenient to blur distinctions between refugee and criminal, migrant and marauder.

This treatment of Mexicans in the popular imagination was typical for the time. There was a voracious public appetite for scenes of border mayhem that was served by photographers-turned-entrepreneurs like Otis Aultman (1874–1943), who found they could make a killing taking such pictures for the booming postcard market. This phenomenon will already be familiar to those who are aware of the violent history of the Jim Crow South, with its some 4,000 lynchings of Black men and women between the end of Reconstruction and 1950.

The Injustice Never Leaves You, published in 2018 by Harvard University Press, documents the disturbing history of anti-Mexican violence during a period of rapid growth and economic transformation for the Lone Star State. Between 1910 and 1920, vigilantes and law enforcement, including the famed Texas Rangers, killed Mexican residents with impunity. The chapter “Idols,” which documents the racial postcard boom, tells us something important about this period: anti-Mexican violence was not just tolerated but glorified.

In reconstructing this brutal history, Martinez, an associate professor of history at the The University of Texas at Austin, relies upon a combination of traditional public and private archives, oral histories, and descendant testimonials. The full extent of the violence was known only to the relatives of the victims.

“It recovers a history of anti-Mexican violence at the hands of vigilantes, law enforcement, and also U.S. soldiers, in the early 20th century,” said Martinez about her work. “What it helps to document is a history that has really been obscured or misrepresented.”

The 1918 case of Florencio Garcia was typical. When he didn’t come home from his cattle herding job one day, his father, Miguel, feared the worst. Over the ensuing weeks—weeks that saw Miguel and others literally scouring the brush in search of Florencio’s remains—his fears were confirmed. Florencio’s remains were found just outside of Brownsville. There were bullet holes in his jacket. Evidence from both eyewitnesses and a Mexican consulate investigation suggests that Florencio was arrested by Texas Rangers just before his disappearance. Three Rangers were arrested, but an all-Anglo grand jury ultimately refused to indict.

Families like the Garcias had a lot working against them. The power structure at all levels sought to minimize the violence. Perpetrators operating in remote rural areas could deal violence and death without scrutiny. Elites on both sides of the border were often more concerned with public perception than helping victims. The need to protect the farming economy gave an incentive to cover up the ugly truth. And the endemic racism of the time naturally made the pursuit of justice both slow-going and perilous.

The political rhetoric of the time, which constantly stoked fears of Mexican banditry and deviance, was eerily similar to today’s anti-immigrant rhetoric, said Martinez. This was one more barrier for victims and their families. “What you see from this period,” she said, “is that people who were victims of lynchings or police homicides or massacres, when those events were called into question, those victims were criminalized.”

The story that Martinez tells is also one of generational trauma. The memory of anti-Mexican violence lives on in communities down to the present.

“The title of the book comes from an interview with Norma Longoria Rodríguez, who spent years of her life, on weekends and in between working and raising children, trying to document the double murder of Jesus Bazán and Antonio Longoria, her great-grandfather and grandfather,” said Martinez. “And when I asked her why she had spent so much time trying to recover this history, she said, ‘It’s an injustice. It never leaves you. It’s inherited loss.’”

Mapping Violence

Martinez’s research on this period gave rise to the Mapping Violence Project, an ambitious work of historical recovery. Leading a research team of graduate and undergraduate students, Martinez began Mapping Violence in 2015 to document cases of racist violence from 1900 to 1930.

“Initially when I was doing the research for The Injustice Never Leaves You,” said Martinez, “I unfortunately came across too many cases of violence in the archive. I couldn’t write about them all. But realizing that those deaths, those cases, had not been reported elsewhere, I saw the need to start collecting those names and the sources that are available to start learning about those events.”

Mapping Violence uses a mix of traditional historical research and digital humanities methods to generate its data. The research will be used to support a wide range of scholarly activity that will include books, peer-reviewed journals, and an interactive digital map where users can research and learn about individual cases. There is also a strong emphasis on public outreach, with plans for historical essays, digital tours, and teaching materials for educators.

Mapping Violence is also broader in scope than many other projects of its kind, said Martinez. Grounded in the assumption that early 20th century terror had an omnipresence in American life, the project brings in cases of racist violence across a range of classes of perpetrator and victim, and modes of violence.

“Some recovery projects will try, for example, to only cover lynchings,” said Martinez. “But if we’re really trying to think about how people lived in a climate of racial terror, we have to think all kinds of different violence.” Martinez notes that Texas Rangers also killed Black people, Indigenous people, and even those, such as Jewish Texans, who are often coded as white now but were not earlier in the nation’s history.

“There are patterns that only expose themselves if you think comprehensively and comparatively about these histories,” said Martinez.

Tragedy and Restoration at Home

Martinez is a native of Uvalde, Texas. Like many in her community, she was deeply affected by the tragic Robb Elementary School shooting of May 2022. In response, she is working with several other UT Austin faculty to develop Recover Uvalde, a grant proposal that, if funded, would address a number of pressing community needs, including mental health, public health, and restorative justice. Her vision for Uvalde shares certain qualities with her historical work: a focus on justice and restoration, an emphasis on community memory and well-being, and a desire to collaborate with others to make things happen.

Just as Mexican communities of the past were not just passive victims but seized opportunities to try to change their condition, so too are Uvalde residents trying to set their community on a healing, self-determining course.

“There’s a need for thinking about Uvalde as potentially being the first restorative city in Texas,” said Martinez. “Uvalde has a long history of neglect by the state and federal government. There’s a conversation to be had about not just meeting immediate needs, but thinking about what restorative transformation means for a community that is still reeling from the aftermath of this massacre.”