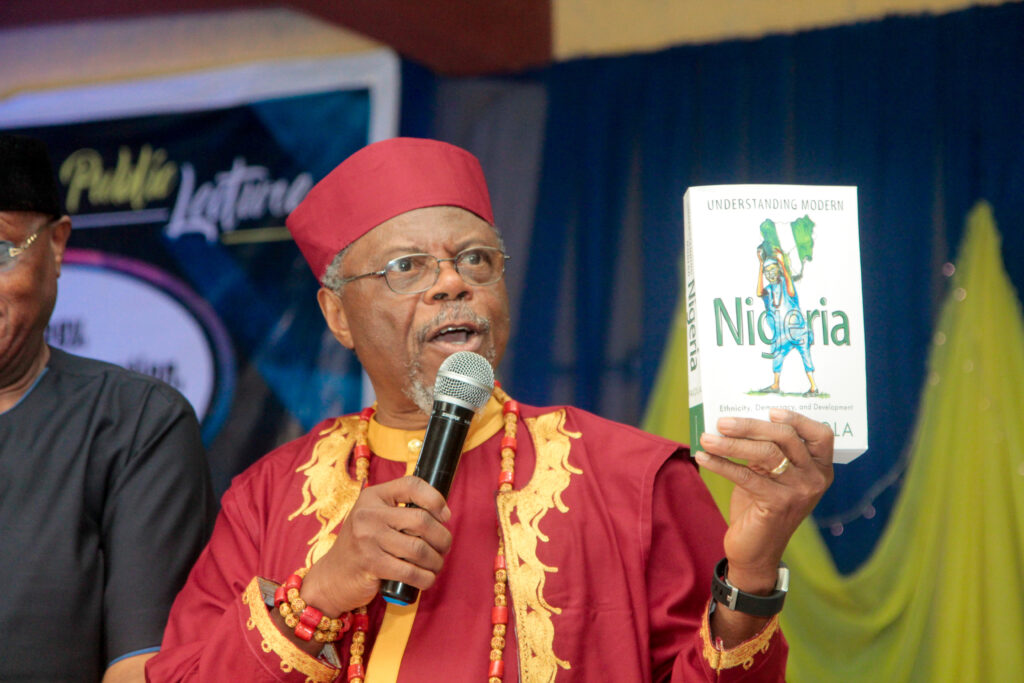

Toyin Falola is a scholar and public figure of global stature. Over the past four decades, he has redefined and expanded the approaches, scope, and effectiveness of African studies across multiple disciplines and throughout the world. Since 1991, he has taught in the Department of History at The University of Texas at Austin, where he holds the Jacob & Frances Sanger Mossiker Chair in the Humanities and the title of University Distinguished Teaching Professor.

Professor Falola’s career has been extraordinary. His wide-ranging publications include more than 200 authored and edited books and countless articles and chapters. His two annual conferences, at UT Austin and in rotating African universities, have been essential sites for the advancement of knowledge and professional development. His editorship of several book series and journals, as well as the publication of textbooks and encyclopedias, have revolutionized the landscape of scholarly research and available resources related to Africa and the African Diaspora. Falola is the recipient of more than thirty lifetime achievement awards, including, most recently, recognition as a Member of the Order of the Niger (MON), which was conferred by Nigerian President Muhammad Buhari on October 11. He has received sixteen honorary doctorates, a Doctor of Letters (D.Litt) degree, and three chieftaincy titles. There have also been eight books written about him, testifying to the magnitude of his achievements as well as to his mentorship and generosity towards students, colleagues, and institutions. Like Chinua Achebe and Wole Soyinka, Toyin Falola has become a household name in many African countries and, as strange as this may sound to many Americans, he is being used as a “prayer point” in some churches with parents saying, “May my child become like Toyin!”

I met Professor Falola when he first arrived at UT while I was a doctoral student in the English department studying postcolonial literature and have been the beneficiary of his mentorship throughout my career. I have experienced firsthand the transformative effects of his guidance, engagement, and dynamic spirit. In this interview, we speak about both his current work and the impact of his long career on African Studies. His superhuman productivity and contributions show no signs of deceleration, revealing his unshakeable optimism in Africa’s future, based on a deep faith in African people and their values, genius, energy, and resources.

Vik Bahl: Which of your recently published books would you recommend for College of Liberal Arts alumni? What would you hope that non-specialist readers might take from it?

Toyin Falola: I would recommend Decolonizing African Studies: Knowledge Production, Agency, and Voice, published recently by the University of Rochester Press. The book contributes to reframing perceptions of Africa, challenging the false and damaging universalist claims of the Western knowledge system that was propounded by colonialism and Christianity.

Africans have suffered severe injuries to their identity resulting from Western arguments that they were a people devoid of knowledge, artistic expression, and creativity in all areas. Leaving people’s history out of their control and reach repositions their mindsets and creates an atmosphere of self-denial and self-immolation.

Decolonization itself can only be achieved by employing multiple methods and strategies of knowledge production, what I have called “pluriversalism,” across all disciplines, in addition to the liberal arts and humanities. Decolonizing African Studies offers African voices that represent alternative knowledge systems, showcasing the best ideas on the transformation of societies. The book discusses African contributions to peace, political economy, and social ethics, while also examining the limitations, impediments, and failures of decolonial projects.

2) You have developed numerous innovative courses over your three decades at UT. Which is one of the most popular undergraduate courses you have developed, and what has made this course so appealing to students?

I teach a course on the United States and Africa that adopts a multidisciplinary approach to examining the history of the political, economic, and cultural relations between the United States and Africa from the early origins of the slave trade to the present. Among the key aims of the course is for students to: develop a base of African and US history; increase their level of awareness of the African Diaspora in the U.S.; obtain a well-rounded contextualized approach to the political, economic, and cultural connections between the United States and Africa; and reevaluate perceptions of Africa, recognizing the vibrant nature of African culture and its presence in virtually all aspects of U.S. popular culture. U.S.-Africa relations have produced a massive African presence in the U.S., with both locations needing and benefitting from each other. Students understand present-day politics in Africa at a deeper level and gain a new understanding of racial conditions in the U.S. based on new perspectives that are often forgotten in the teaching of international relations.

3) What do you believe has been the impact of the The Toyin Falola Interviews, the online interview platform you established during the COVID-19 pandemic? The series has included interviews with key figures in African academics, arts, activism, and politics, including interviews with former presidents of Nigeria, Ghana, and South Africa. The audience for some of these interviews has reached upwards of 35 million people!

The wide audience for The Toyin Falola Interviews confirms Africans’ interest in diverse forms of knowledge that are essential to their existence, going beyond just academic value. The platform offers an opportunity for Africans, especially younger ones, to understand their plight, which cannot be generalized across the continent, regions, or generations—notwithstanding some common problems stemming from slavery, colonialism, and the continued imperial adventures of the West on the continent. Through this platform, Africans with a range of irreconcilable challenges and agitations have strengthened bonds across cultures and civilizations, especially when they come together to voice their fears.

The platform also demonstrates to an international audience what Africans are confronted with, allowing non-Africans to understand the roles they may play in the dynamics of the continent, whether based on complicity or support, including how an interested diaspora community can intervene in or approach urgent concerns. We have brought people together to exchange ideas, debate differences, and maximize the intellectual resources with which Africa is blessed, thereby promoting unity and rejuvenating energy.

4) Another of your recent books is Nigerian Literary Imagination and the Nationhood Project. How do you see the connection between the writing of history and literature?

The griot in traditional African societies was a historian, a poet, a singer, and a chronicler, and was considered the compass for navigating a society’s collective history. As griots were not necessarily producing written texts, Western scholars interpreted Africa as lacking history and historians prior to colonialism. Moreover, even professional historians, while not being allowed to change events to suit their interests, are not precluded from introducing creativity to their craft to achieve their objectives, just as literary experts play with chronology.

The absence of professional historians, however, did not translate to the absence of literary experts. In fact, nearly all African civilizations had people who created and performed literary and artistic productions that offered emotional, social, and intellectual edification and comfort. They used their knowledge of history, along with their creativity, to effectively transmit knowledge and values and to familiarize the coming generations with the activities of their societies. Those who grew up in African countries have enjoyed access to these collective modes of African history and culture through the teachings of elders and opportunities to meet and interact with various literary and cultural creatives.

The relationship between literature and history, then, is a productive one, especially since they both can be used as instruments of social mobilization, economic rejuvenation, and political transformation. Literary experts could be described as seers who can accurately predict the future. As much as literary works may be entertaining, writers and performers also direct attention to larger issues and use their works to warn humanity of possible dangers and enable us to understand the need for moral uprightness, and to adhere to the ideas and values that have been formed in their society.

5) Can you reflect on your role in mentoring the next generation of scholars?

There is a common saying that only individuals who have survived wars can relay history to others. Those of us who are survivors on the battlefield of knowledge production are qualified and obligated to take critical measures and roles to enhance the likelihood of a desirable future for the coming generations of scholars—those who will potentially make positive contributions to a resourceful African future so that unborn generations may thrive.

When we organize conferences and seminars, for example, we are providing opportunities to new and established scholars to showcase their research findings to the world. This energizes them and lightens their spirit as they continue on that trajectory. Beyond this, conferences and symposia have provided important opportunities for scholars to create webs of relationships with others in similar fields.

6) You have been a professor at The University of Texas at Austin for more than 30 years. What role has UT played in helping you execute your vision for African Studies?

First, let me state my unreserved appreciation for the graciousness of The University of Texas at Austin, for it has functioned well beyond a corporate organization for me. It is my second family and has provided support and succor when I needed it most. In Africa, we believe that, in the absence of deterrence, all humans have the potential to survive and reach heights that no one can ever have imagined. UT has given me the environment where the actualization of my dreams has been possible.

UT has supported my vision, including through significant financial commitment, and this has played a significant role in making our university the go-to academic area where people may contribute and retrieve knowledge of uncommon innovation and quality related to African studies. This is a testament to the institution’s respect both for me and for my field. I will always remember the university’s uncommon benevolence toward me.

![[Monday 12:57 PM] Oppenheimer, Daniel J Pencil drawing by Adeoye Hassan, from a reference photo by Michael Efionayi. Courtesy of Toyin Falola.](https://lifeandletters.la.utexas.edu/wp-content/uploads/2023/01/TF-pencil-art-scaled-e1674856516773-1920x1300.jpg)