Here is the basic anatomy of a story: there’s a beginning, a middle, and an end.

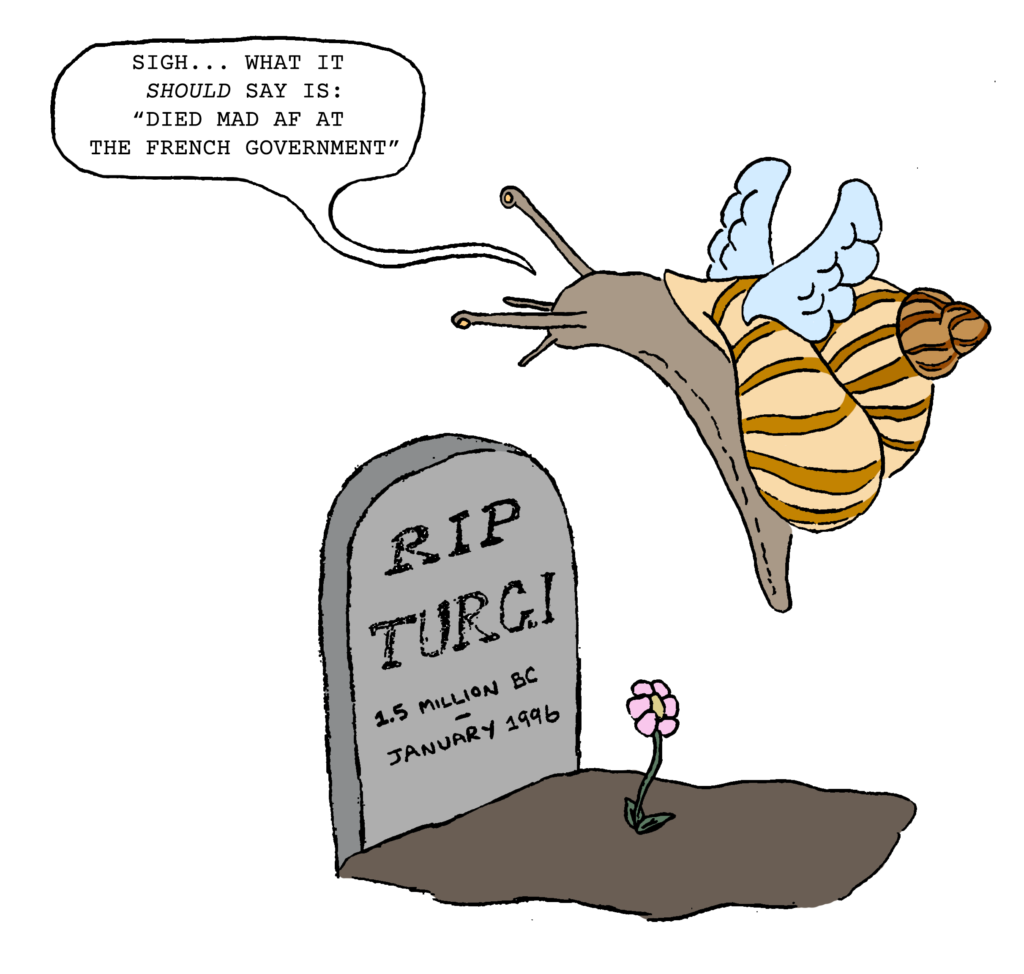

Here is the abridged story of Turgi. For a million years, the Partula genus of tiny tree snails lived in Polynesia and evolved into more than 120 species spread out over the archipelago. In 1996, after the failure of a captive breeding program meant to revive the species line, the last Polynesian tree snail from the Partula turgida species, named Turgi, died in the London Zoo.

Consequent media coverage included a kind of obituary on the death of Turgi in the Chicago Tribune: “It moved at a rate of less than 2 feet a year, so it took a while for the curators at London Zoo to be sure it had stopped moving forever.” This is how news coverage tells the story of the “endling,” a word created to describe the last known individual of its kind.

The first job in developing any kind of story is to give your character a name. “Martha. Ben. Orange Band. 淇淇 (Qi Qi). Turgi. Incas and Lady Jane. Benjamin. George. Celia. Laña. Toughie. Lonesome George. Name after name after name. These are names of the dead,” writes author and historian Lydia Pyne in her latest book, Endlings: Fables for the Anthropocene (University of Minnesota Press, 2022), which considers the narrative fates of endlings. “Naming creates a familiarity between us and the dead. These names are a way — fair or not — to lay claim to these animals and their stories; in a bit of dark, anthropocentric irony, perhaps we use these names to humanize them. And these particular names are a roll-call of extinctions and endings on earth.”

A visiting researcher at the Institute for Historical Studies at The University of Texas at Austin, Pyne’s writing and research often involve richly textured biographies that examine the history of science and material culture. Her background in history and anthropology — she earned her master’s from UT Austin and her doctoral degree in biology from Arizona State University — are embedded within her latest research into how humans talk about endlings as a form of storytelling.

Pyne came to her work on endlings in December 2020, amid a COVID-19 variant wave just after the U.S. elections. At home with her then-seven-month-old daughter and without much other social contact, she began to read to her daughter out loud, selecting atypical children’s books, including Octavia Butler’s Parable of the Sower, Albert Camus’s The Plague, and Maria Dahvana Headley’s new translation of Beowulf. It was Headley’s specific use of the word “extinct” within a section of Beowulf known as the “Lay of the Last Survivor” that sparked Pyne’s interest in how we write about the last survivors of non-human species.

“Taken together, I felt like endling stories formed a modern compendium of Aesop’s fables — animal stories with morals that exist to be told to teach us how to be better humans here in the Anthropocene,” Pyne later wrote. In mediation between humans and nature, these fables of the Anthropocene, a period in the Earth’s history defined by the impact of humans, relate a wildly divergent set of morals, lessons, and opportunities for reflection.

Take “Benjamin,” the last Tasmanian tiger. Eighteen million years ago, Thylacinus cynocephalus could be found across Australia, Tasmania, and as far north as what is now Papua New Guinea. They were depicted in ancient Aboriginal rock art at the red rock of Murujuga. The thylacine would later be systematically slaughtered by 19th- and early 20th-century British settlers in Tasmania before extensive habitat destruction spelled their doom in the first half of the 20th century. In 1936, the thylacine endling died in captivity at Beaumaris Zoo in Hobart, Tasmania. Its name, however, wasn’t Benjamin. It wasn’t even a male. But a Hobart resident with no ties to the Beaumaris Zoo gave a radio interview in which she fabricated an entirely false record of the thylacine’s time at the zoo, including that she was a male and that zoo staff called her “Benjamin.” The story stuck. Benjamin became an icon for environmental conservation in Australia and later reappeared in a 2001 exhibit titled Tangled Destinies at the National Museum of Australia. That exhibit was responsible for popularizing the term “endling.”

Benjamin’s story, “like all good stories,” writes Pyne, is really a set of interlinked and nested narratives. In this case, she writes, it “offers its audiences a way to think about extinction and loss of species in nuanced ways.” Benjamin’s stories work by making a species story digestible — deconstructing it into “a beginning, a middle, and an end — in effect, an origin, a life history, and an extinction.” Along the way, we are able to explore ideas of colonialism, environmental trauma, the role of conservation efforts, and how we collectively mourn a species and process loss and harm.

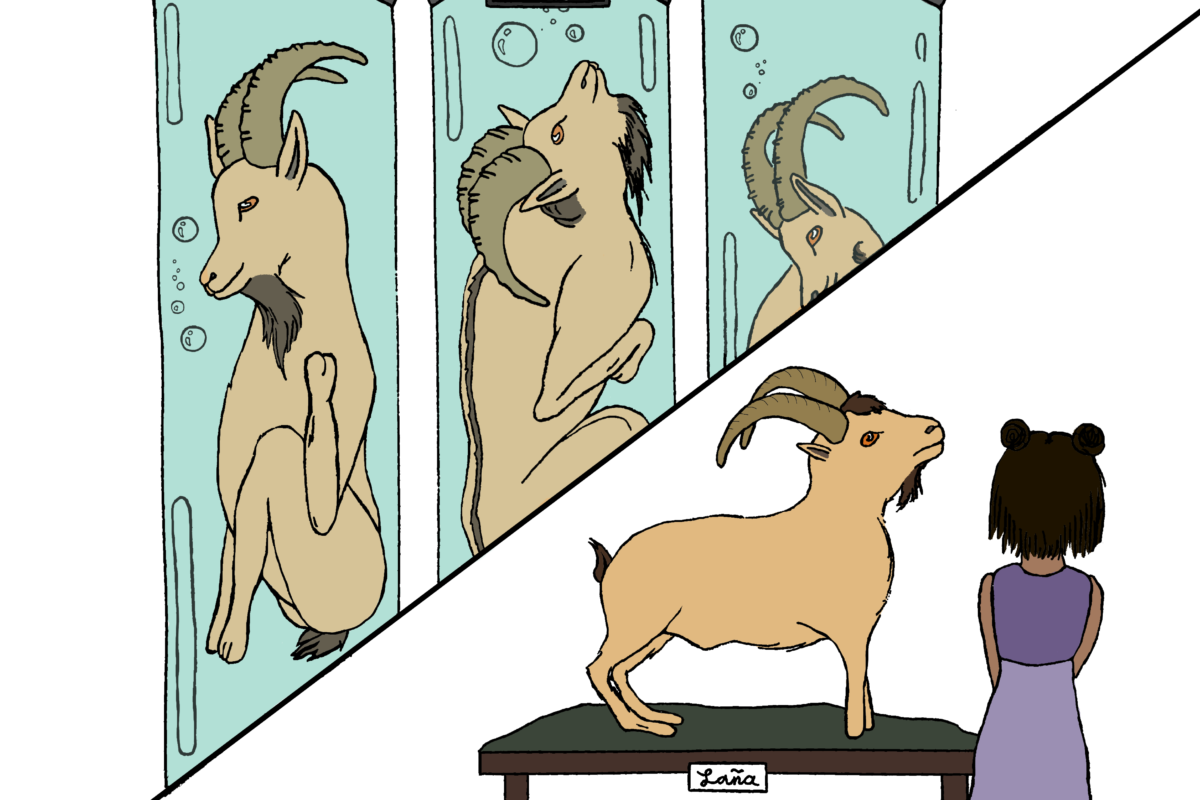

Other endling stories are similarly complex. Take, for example, the story of Celia, the last Pyrenean ibex, Capra pyrenaica pyrenaica, who died in the Spanish Pyrenees on January 6, 2000. Three years after her death and her species’ extinction, a team of scientists successfully managed to clone Celia using a method similar to the one used to clone Dolly the sheep. For a full seven minutes, Celia’s clone was the only record of de-extinction in human history. To complicate matters further, “Celia” is also “Laña,” the name used by people in the village of Torla in Aragón, Spain, in reference to the same endling. Laña also died on January 6, 2000, but she was memorialized after her death in Torla as a specific loss belonging to this region of the world. When talk of cloning Celia/Laña reemerged in 2013, the people of Torla founded a museum dedicated to the “burcardo” (the Spanish word for the Pyrenean ibex) and fought to bring Laña’s taxidermied remains to be exhibited in the community where she “lived” as a species.

Celia/Laña’s story, says Pine, is a story about how we summon afterlives among different cultures. She can represent a double extinction and a dubious conservation effort while also exemplifying how one species might “live on” in a museum.

Research for Endlings took Pyne to South Africa, where she collaborated with South African isiZulu-speakers, scientific researchers, and translators to understand how the isiZulu researchers were combatting species extinction. This team is in the process of translating 180 scientific papers published in English into six African languages with the idea that open access will allow “language to evolve with wildlife.” In an exhilarating turn for Pyne, when discussing the lack of a word for “endling” in isiZulu, her isiZulu-speaking colleagues started to construct one on the spot. “It felt like watching language speciate rather than witnessing something go extinct.”