Nathaniel K. Gilmore on Why Montesquieu’s Writings on the Rise and Fall of Rome Still Matter Today

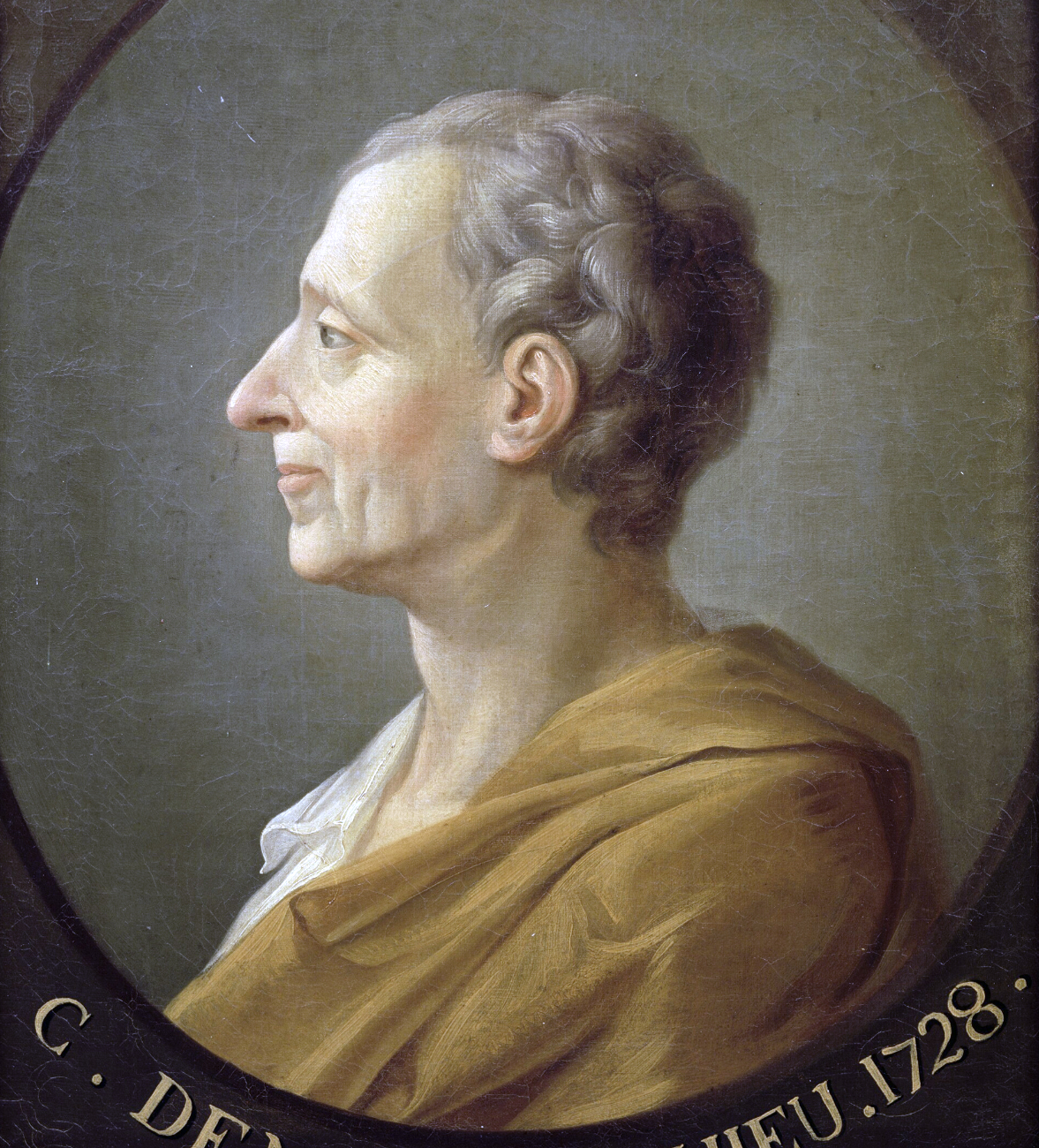

French 18th-century philosopher Charles Louis de Secondat, known to us by his baronial title Montesquieu, is most famous today for advancing the doctrine of separation of powers. This revolutionary Enlightenment political theory helped convince the architects of the U.S. Constitution to divide our federal government between independent judicial, legislative, and executive branches. Montesquieu was also renowned in his own time, however, as a preeminent scholar of Roman history, authoring the 1734 treatise Considerations on the Causes of the Greatness of the Romans and their Decline.

How did one of the 18th century’s greatest students of Rome — Montesquieu predated and influenced Edward Gibbon— become its foremost voice for balance and moderation in the construction of the modern state? What lessons did Montesquieu take from the epic story of Rome, and how did he build upon those lessons to create a body of political theory that continues to inform some of the best governments, and accurately describe the follies of some of the worst, in the world today? These are some of the questions explored in Montesquieu and the Spirit of Rome, the new book by Nathaniel Gilmore, assistant professor of government at The University of Texas at Austin.

The lost world of Roman grandeur, Gilmore says, has been a siren song on the horizon of Western history throughout the centuries, and it still calls to us, both as a dream and a warning. “Some of the enticing ideas that Rome forces you to look at remain enticing today, both for good and for evil,” Gilmore says. “The unity of Roman law, its predominance over Europe, the dream of a single law code ruling everyone and bringing about harmony — it seems we just can’t quite get away from these things.”

Preoccupation with that ancient grandeur loomed large in the decades after Montesquieu’s book on Rome was published, when revolutions in America and France remade the political order on both sides of the Atlantic. Napoleon, for example, drew heavily on Rome’s military symbols, and the American Founders adopted Roman pseudonyms for their debates in the Federalist Papers. To understand why these epochal figures draped themselves in such symbolism, says Gilmore, one must look to Montesquieu, who was a key source on the subject.

The conclusions that Montesquieu drew from Rome were as much about its failures as its successes. For instance, Gilmore writes, Montesquieu was a great admirer of Tacitus, who chronicled the depravity and misrule of the early Roman emperors. Montesquieu was also unique in his era for his efforts to understand the Byzantine period after the fall of the Western Roman Empire. It was a time, wrote Montesquieu, when Christianity combined with existing strains of Roman rule to produce a new kind of despotism. From these examples, five centuries apart, Montesquieu drew a lesson of moderation as a way of circumventing despotism.

“You have to understand what you can and can’t do in a situation,” Gilmore says of Montesquieu’s thinking. “Attempting the impossible is the first path to radicalism. Since you are attempting to bring about what can’t actually be brought about, you are compelled to take more and more drastic measures to make it happen.”

Montesquieu’s ideas on moderation have had the greatest impact on those who sought to carefully construct a constitutional system that would avoid too much accumulation of power in any one person or office.

“James Madison above all, among the Founders, adored Montesquieu,” Gilmore says. “He goes so far as to call Montesquieu the Oracle of the Enlightenment. He is the prophet of ‘what could be done’ in modern times, beginning with the establishment of a certain distribution of powers that would maintain the strength necessary to keep a state in order, while limiting that state from becoming oppressive or despotic.”

Another fascinating aspect of Montesquieu’s work on Rome, says Gilmore, involves the quality of active citizenship that today we’d probably describe as “patriotism,” but which Montesquieu refers to as “virtue.” He saw Rome, especially in its years as a republic, as an unparalleled font of public virtue, where citizens’ sense of worth and purpose in life was innately tied to the welfare of their homeland, which they had some small democratic part in managing. He saw this virtue as pivotal to Rome’s rise to dominance over the Mediterranean world, and this virtue’s eventual decay as an important part of the story of Rome’s fall. This narrative arc led Montesquieu to reflect on the role of public-spirited virtue in modern societies.

“Montesquieu insists that are public without virtue cannot survive,” says Gilmore, “no matter how well distributed its powers are — that virtue is an animating force, and that it was in Rome, more than in any other environment, that this virtue truly flourished.”

At the same time, says Gilmore, Montesquieu was wary of calls to restore a Roman-style virtue in the nations of 18th-century Europe. He thought that England, for instance, was too commercial a society for Roman-style virtue to be instilled in the public. It simply wasn’t realistic in context, and efforts to deny such limitation could lead to tyranny. It’s an important lesson for readers in the U.S. as well, points out Gilmore, because our country today is even more of a commercial state than England was in the 18th century. So where does that leave us, in need of collective virtue but structured around values that militate against it?

Montesquieu has no easy answers on this subject, says Gilmore, just hard questions. “He wants to prod you to figure out for yourself how much those old drives and motives are still necessary to us, and what we can do to try to promote them while accepting that ours is a regime that will never be a factory of virtue the way Rome was,” Gilmore says.

Imperialism — whether of the Roman, British, or American variety — also has a tendency to undermine and squander public virtue and patriotism. Montesquieu was well aware of this conundrum. The same quality that keeps us invested in maintaining the greatness of our own republic also tends to lead us to dream of imposing our laws on others.

“That paradox haunts the virtuous republic,” Gilmore says. “There may be a danger that our very success in establishing an empire that proves our greatness could corrupt the thing that brought about the greatness.”

This is the story of Rome, which gained the known world and lost itself along the way. This loss of liberty, in Montesquieu’s telling, is a tragedy for the ages, one that ought to be studied so that it does not happen again.

“Montesquieu gives us Rome as an example of a place where an extraordinarily free society did a number of things that managed to corrupt that freedom,” says Gilmore. “He looks at the ways in which they toppled their distributions of powers, the ways in which they undermined those highest human motives that can sustain a free state.”

What Montesquieu offers today, says Gilmore, is a historically informed understanding of the consequences of losing these balances and these virtues, one that could provide insight into our own century of strongmen and simmering despotism.

“It becomes all the more urgent for us to be able to give a coherent account of what despotism is and why it’s so bad,” Gilmore says. “In Montesquieu’s analysis of Rome, we see one of the greatest accounts of that ever given.”