The data are startling. Life expectancy in the United States is lower than in any other high-income country in the world. In 2019, the average American could expect to live 78.8 years, which was 5.7 years less than the average person in Japan, the nation with the highest life expectancy. Closer to home, Canadians enjoyed a life expectancy of 82.1 years in 2019. In the UK, life expectancy was 81.3 years.

“U.S. life expectancy falls between two middle-income countries — Cuba and Albania,” wrote sociologist Mark Hayward and a team of colleagues in a recent paper in the journal PLOS ONE.

It is even worse than that, says Hayward, the Centennial Commission Professor in the Liberal Arts at The University of Texas at Austin. After many decades of slow increase in life expectancy, the trend in recent years has been going in the wrong direction. Our average life expectancy as Americans is getting shorter.

Why this is the case has been the mystery that Hayward and his colleagues—an interdisciplinary team of sociologists, demographers, epidemiologists, biostatisticians, and political scientists from across the country—have been trying to unravel for more than a decade. Why is one of the wealthiest nations in the world experiencing a significant decline in a such a major indicator of well-being?

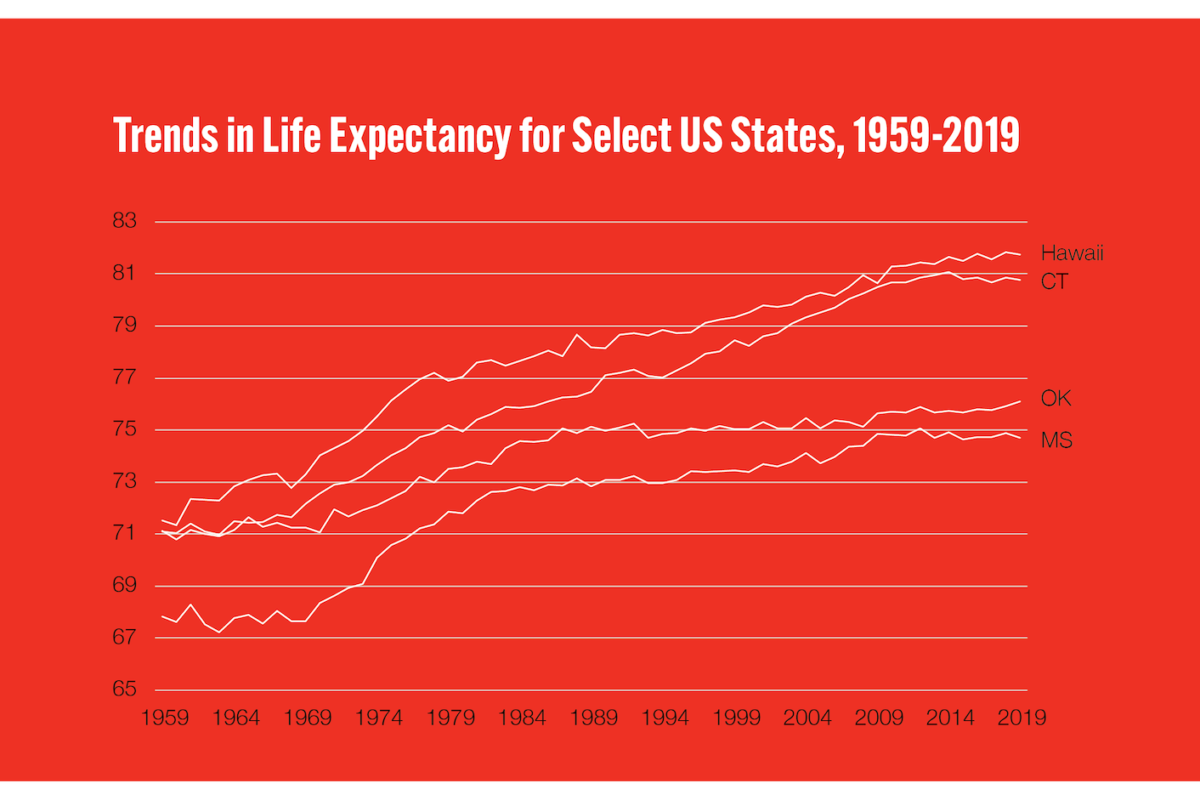

One key fact, says Hayward, is that this seemingly national problem is in many respects a state problem. In the U.S., your life expectancy varies dramatically depending on where you live. In 2019, a resident of Hawaii could expect to live to 80.8 years, a resident of Connecticut to 80.3, and a Texas resident to 79. In contrast, the life expectancy in Oklahoma was 76.1 years. In Mississippi, the state with the lowest life expectancy, it was just 74.4 years, about six-and-a-half years less than Hawaii’s.

Another key fact is that these state disparities weren’t always nearly so pronounced. Things looked very different in the 1970s, when life expectancy in the U.S. was climbing steadily, including, notably, in lower-performing states like Mississippi and Oklahoma. Improvements in health were broadly shared, Hayward says, and reflected the culmination of both FDR’s New Deal and the Great Society program of the ‘60s, with their host of federal policies like vaccinations for diseases like mumps and measles, increased access to birth control, stronger worker and environmental protections, improved educational access, the establishment of Medicare and Medicaid, and the Voting Rights Act and Civil Rights Act.

Then something important changed.

“Why did Oklahoma and Connecticut have exactly the same life expectancy in 1960,” says Hayward, “but now they anchor the high and low ends of life expectancy in America today? What happened?”

Hayward first began exploring this issue about 15 years ago, with his then-graduate student, Jennifer Karas Montez, who has gone on to become an endowed professor at Syracuse University and is the leader of the national team of researchers.

What happened, they argue, is that since the 1980s, responsibility for a variety of policies that can affect health has been steadily transferred from the federal government to the states, which have in turn set their own courses — in some cases, dramatically different ones — on issues ranging from tobacco restrictions to gun control, abortion to environmental regulations. The ramifications of these disparate policies are significant, reaching well beyond the question of how long a person will live.

“State policies affect nearly every aspect of people’s lives, including economic well-being, social relationships, education, housing, lifestyles, and access to medical care,” Hayward, Montez, and their coauthors wrote in a 2020 paper in the Milbank Quarterly. In their research, they rated state policies along a conservative-liberal continuum. Policies that expanded a state’s economic regulatory powers, protected vulnerable groups, or diminished punishments for so-called “deviant” social behavior were categorized as “liberal.” Policies that did the opposite were categorized as “conservative.”

They found that more liberal policies — in such wide-ranging areas as tobacco access, immigration policy, civil rights, labor law, the environment, gun control, LGBT rights, and abortion access — were almost always associated with longer life expectancy in U.S. states, in some cases by almost a year. Stronger environmental laws, for example, limit exposure to toxins that damage health. Civil rights laws protect people from the mental and physical health risks connected to discrimination. Policies that benefit workers, such as higher minimum wages and paid family leave, lead to improved economic and physical well-being.

There were a few notable exceptions to this link between liberal policies and longer lives. For instance, the research team found that more conservative marijuana policies (i.e., more restrictive or punitive policies) were associated with greater life expectancy. Overall, however, “U.S. life expectancy would be 2.8 years longer among women and 2.1 years longer among men if all states enjoyed the health advantages of states with more liberal policies.” In fact, these values would substantially raise U.S. life expectancy relative to other countries, making the U.S. more similar to Belgium than to middle-income countries.

It might be tempting, Hayward says, to blame Americans’ dwindling life expectancy on individual choices. “People often say, ‘Well, people eat too much or they drink too much, they smoke too much or whatever.’ And individual choices are important. But behind those behaviors lie a whole set of factors that play into them,” including policies that support or undercut healthy choices. For example, he notes, state cigarette taxes vary from as low as about 50 cents a pack in states like Mississippi to more than $4 a pack in states such as New York and Connecticut. Not surprisingly, states with higher cigarette taxes have lower smoking rates and higher life expectancies.

Such policies, and policy differences, seem to have particular impact on people with lower levels of education. In fact, the relative well-being of people at the lower end of the education scale is what drives most of the difference in life expectancy across states. “Well-educated people are pretty much exactly the same,” Hayward says. “It doesn’t matter if you live in Mississippi or Connecticut. But people at the lower end of education are not the same everywhere.”

A higher minimum wage policy, says Hayward, won’t matter much to well-educated people who earn annual salaries in professional jobs. But it can make a big difference to less educated people working in hourly jobs. A generous earned income tax program, similarly, will only help relatively disadvantaged people. The more you stack these types of policies on top of each other, in either direction, the more impact it is likely to have for the life expectancies of people who are most economically vulnerable.

This is particularly the case, says Hayward, for poorer and less educated women. Restrictive abortion policies have limited the ability of women’s healthcare clinics to offer vital non-abortion services, such as breast-cancer screenings. Loose gun-control laws are associated with higher rates of gun-related homicides of women by their partners. Women are also more affected than men by state policies related to economic security — the minimum wage, the earned income tax credit, paid family leave, Medicaid — because they are more likely to work low-wage jobs or to be raising children or caring for elderly parents.

One of the more alarming trends in the data, says Hayward, is that life expectancy seems to be plateauing or decreasing for more and more cohorts of people over time. “First,” he says, “we saw the leveling-off of improvement among less-educated people. Then it spread up to high school graduates, then it spread up to people with some college. Now the only group that’s improving in life expectancy are college-educated people. So it’s not just the most disadvantaged anymore. It’s everyone who doesn’t have a college degree.

Delving into these issues forces a confrontation with electoral and legislative politics that isn’t always comfortable for an academic, Hayward acknowledges. His other research interests cover a wide range of issues that influence the health of Americans, including education, race, gender disparities, and marital status. He is also currently working on a biosocial project that looks at how early-life events affect a person’s risk of developing dementia.

His work on state life expectancies “is so different from what I normally do, but it’s simply because we had to answer the question why,” Hayward says. “It took us a while to really blend the politics, the political science, the policy issues together with what’s going on, on the ground, in terms of health and mortality.”

When asked about solutions to the declines in life expectancy, Hayward is cautious not to simply recommend a grand bundle of “liberal” policies for every state. “I view it as a nationwide conversation, but I don’t view it as a nationwide fix,” he says. “States are different. They have different ecologies, they have different kinds of population groups, and it’s really a matter of how you invest in your population within your state.”

He’s also hopeful that some health policies, at least, can be de-coupled from partisan politics. “I don’t think the trends are irreversible.”

Whatever the politics, Hayward and his colleagues are committed to sharing their findings with as wide an audience as possible. That means everything from being available for press interviews to prioritizing publishing in open-access journals such as PLOS ONE.

Bringing academic research into the public discourse has long been a priority for Hayward. During his recent tenure as editor of the journal Demography, for instance, he led its transformation to an open-access publication, and he spent the fall of 2022 participating in Phi Beta Kappa’s Visiting Scholar Program, which brings distinguished academics to universities around the U.S. to connect with undergraduates and faculty and give public lectures.

“This is not an academic exercise for us,” he says of the work he and his colleagues do. “We’re doing this because we care passionately about the well-being of Americans. We’re all population health scientists, coming from different disciplines, working together, and we want to make a difference. It’s about improving people’s lives ultimately — that’s our goal.”