The Harry Ransom Center (HRC) at The University of Texas at Austin is world-renowned for its rare books and manuscripts. But to tell a fresh story about Jane Austen, one of the most popular writers who ever lived, the HRC needed to team up with an Austen scholar willing to go places the HRC couldn’t and whose entire focus is on the lesser-known places Austen, or rather her books, have been.

That scholar is Janine Barchas, professor in English literature at UT Austin. In a recent conversation with Life & Letters, she reflected on her 2019 “Austen in Austin” collaboration with the Ransom Center, its impact on Austen appreciation culture, and what it meant to her as a career milestone.

“A public exhibition is kind of a flashpoint, if you will, for research and outreach to kind of meet and interact,” said Barchas. “And that, of course, is what the HRC tries to do with its exhibition space, to sort of showcase what it is that scholars do. And so this was a wonderful opportunity that I was given to be able to kind of show that interaction.”

Jane Austen is a subject that readily lends itself to this kind of public scholarship. Over 30 million copies of Austen’s works have been sold worldwide. The world is swimming in Austen film and theatrical adaptations, book clubs, fanfics, sequels, spin-offs, cosplay, and yes, porn parodies. Though Austen achieved no fame during her lifetime and earned a mere £684 from the four books she published while alive (about $67,000 in today’s dollars), the legions of “Janeites” today are enough to ensure her a place alongside Shakespeare, Dickens, and Stephen King as authors whose works move the pop culture needle.

“That’s just the nature of Jane Austen,” said Barchas. “You know any project that you do about Jane Austen is going to be, ‘You build it. They will come.’ It’s going to attract a much larger audience than some of the other authors that are on my syllabi, like Samuel Richardson or Jonathan Swift.”

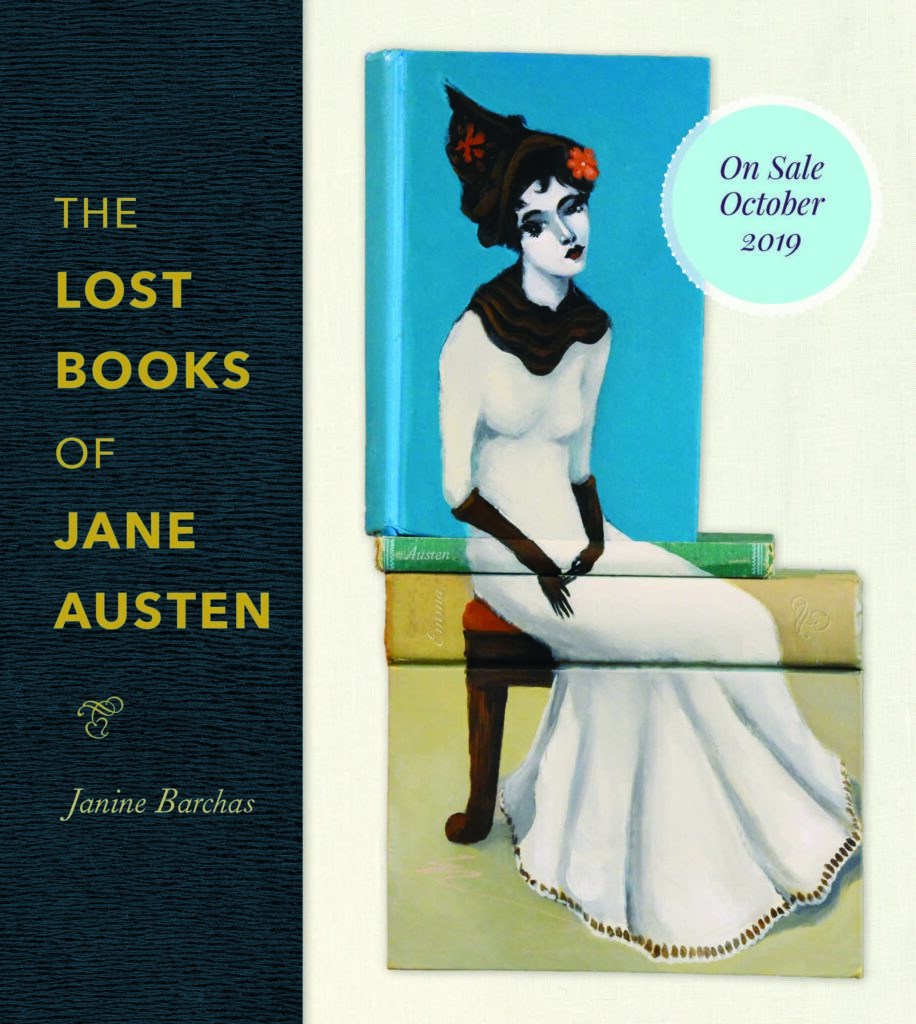

Barchas made a splash in 2019 with her lauded history of Austen, The Lost Books of Jane Austen. The book is credited with adding to our understanding of Austen’s rise to literary stardom during the Victorian period. The “lost books” refer to cheap editions of Austen’s works printed in the 19th century — shoddy reprints that did as much to spark Austen appreciation culture as highbrow literary editions ever could.

It was these cheap reprints that brought Austen’s work to the wider public. As Barchas documents, they were sold at railway stations for one or two shillings — affordable for England’s working classes. As unlikely as these books were to be cherished and collected by scholars, they played an outsized role in building Austen’s early readership.

These findings point to the advantages of Barchas’s scholarly approach, which gives priority to books as physical artifacts. Museums and archives tend to have a bias toward rare, beautiful, or other distinct objects, while books that Barchas studies were consumer goods first, keepsakes second. It would take an individual enthusiast, or a dedicated scholar, to find those few books that were valued enough by their owners not to wind up in the dustbin.

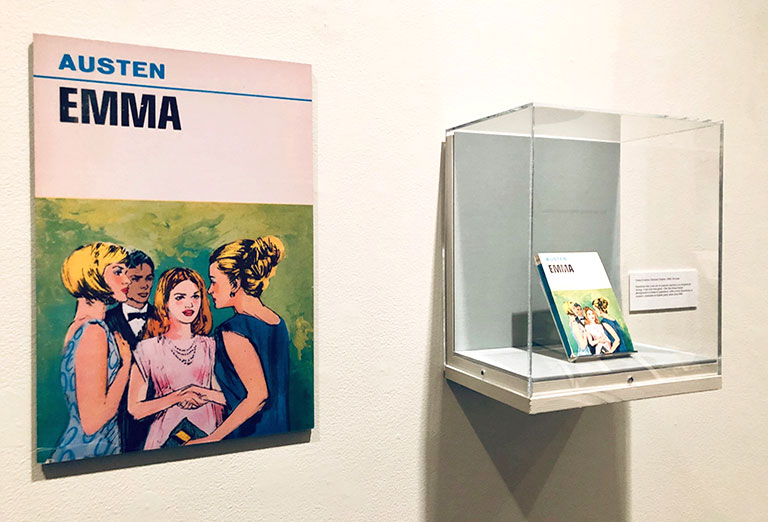

The HRC exhibit, “Austen in Austin,” brought this large history down to exhibit-sized scale, offering Austinites an illustrated tour of Austen’s world using Barchas’s fascinating finds as stops along the way. It also invited visitors to entertain some of the same questions that animate Barchas’s work: What assumptions are baked into notions of what constitutes an “important” version of a book? What new understandings does elevating the “cheap” Austen enact that just rereading her words to the nth degree — which many thousands already do — does not? Or, as Barchas asks in a 2019 blog post, why are some books collected and others merely read?

“Cheap books tell a story about Austen’s fame that differs from the record of precious first editions painstakingly safeguarded by collectors,” Barchas writes. Her work, in tandem with the HRC exhibit, offers a tell-tale glimpse into the everyday Austen, a writer first seen by many wearing natty garb, standing in stark contrast to the genteel icon given currency by the fine editions.

And it’s this protean Austen that, as much as anything else, shines brightly after all the dust and detritus is stripped away. For Barchas, this ability to be responsive to the needs of the moment is what makes Austen remarkable.

“The latest Jane Austen adaptation on Netflix, for example, was a total disaster, and everyone should be in jail who was involved in making that,” Barchas said with a laugh. “But it is yet another instance of Jane Austen being grabbed and adopted, reworked for the next generation. So this is a constant.”