On a warm April afternoon, in the Visualization Laboratory at the heart of UT Austin’s campus, a vast screen towered over a group of students at a podium. On it was a three-dimensional digital recreation of a busy street from 19th-century Yokohama, Japan, complete with cherry trees in bloom, a rickshaw waiting for its passenger, and row after row of solid-looking wooden beams in front of wooden buildings. At the podium, a clack of buttons, and then the scene was moving, buildings and blossoms passing by as a student led the audience on a tour of the historical scene.

“This is incredible,” said Adam Clulow, a professor of history at UT Austin, as he watched the city street unfold. “And you think this kind of scene is reasonable to build in a semester?”

“Oh, for sure,” said the student in charge of the controls. “Very achievable.”

From the audience, where I sat admiring the cherry blossoms, this assertion seemed incredible. Then again, here was the proof: six undergraduate students, led by postdoctoral fellow Jessa Dahl, really had put this digital simulation together in a matter of months. When they started, Dahl told me, they had only a collection of archival photos. Now they had the beginnings of a virtual city.

The Yokohama project, impressive as it is, was only one of three projects supported by UT Austin’s JapanLab in spring 2023. A one-of-a-kind digital humanities laboratory housed within UT’s Center for East Asian Studies, JapanLab began in 2020 when Clulow asked four undergraduate history students to develop a fully functional video game based around a famous episode in Japanese history. Two years later, it’s grown into an extended collaboration between the Department of History and the Department of Asian Studies, supported by funding from the Japan Foundation and the College of Liberal Arts. During that time its students have developed some five games and counting, along with a slew of other digital humanities projects related to Japanese history, language, and culture.

The idea now is the same as it was at the beginning, say Clulow and his JapanLab collaborators Mark Ravina, professor of history, and Kirsten Cather, director of the Center for East Asian Studies. By giving undergraduate students the freedom and support to develop fully realized digital projects, the lab both provides students with desirable, job-ready digital skills and creates interactive educational content for use in classrooms around the country. It also serves as a model for educators more broadly.

“When we started this project, this notion of students in the humanities developing a video game seemed quite difficult to do,” Clulow says. “So part of this whole project is to be proof of concept, showing other people in the humanities, other people in Japanese studies, but also more generally, that your students can do this.”

The obvious question for JapanLab is, of course, why video games? Of all the available formats for digital educational content — and the JapanLab site itself offers primers for using timelines, mapping software, and podcasts in classrooms, among other formats — why the concentration on a medium usually associated with leisure, not learning?

“It’s because the students play them, so they’re intimately familiar with the genre,” Clulow says. “But it’s also because developing a video game requires so much knowledge. You have to come up with the artwork, with the narrative and characters. So when you have students designing these games, it’s a transformational learning experience. They start thinking about how things are going to look, how the characters are going to look, what they’re going to say, and it’s all rooted in history.”

“We’re teaching students now for whom there has always been the internet,” Ravina adds. “So for them, it’s almost the opposite question: ‘Why would I assume that our primary way of getting information is through the printed page?’”

Clulow and Ravina say that working with games and other digital projects requires students to flesh out their understanding of a historical period or concept in a way that a typical term paper simply doesn’t. For one thing, a game requires characters and a narrative, meaning their creators have to first research plausible historical characters and then transform their findings into shape and color. But historical games also require students to wrestle with challenging context, then find a way to communicate that to a general audience. It’s one thing to study, say, the Perry Expedition — which forcefully opened Japan to foreign contact and trade in the 1850s — and another entirely to represent the complex reactions of Japanese leaders in a way that’s both accurate and engaging.

In Ghosts Over The Water, one of JapanLab’s largest releases to date, students managed to do exactly that. The choose-your-own-adventure-style game leads players on a tour of Tokugawa Japan in the immediate aftermath of the Perry Expedition’s arrival. The narrative features more than 15 historically based characters and over 130,000 words of dialogue, a word count higher than that of a standard Ph.D. dissertation. Ghosts is now available for free download on the popular gaming platform Steam and has already been used in classrooms across the country.

The student teams that create games like Ghosts or other digital humanities projects like the 3D Yokohama recreation are small, usually only four or five strong, and led by a single faculty member or post-doctoral fellow. They also represent a range of majors. “We recruit students from all over the university,” Clulow says. “So it’s humanities students who study literature and history but it’s also pulling in students from computer science or other STEM disciplines who wouldn’t necessarily take courses in COLA.”

Students must apply to join a specific JapanLab project, and they receive internship credit for their work — though some, Clulow says, choose not to receive any credit at all, instead working purely for the experience.

Over the course of a semester, the teams meet weekly with their project leads, who provide them with necessary historical background and context. JapanLab also brings in experts from the gaming industry to give workshops on the basics of game design and development. “You get so much credibility with students when you can invite these experts in,” Clulow says, “and they do so much real work in helping the teams build a narrative and understand how their humanities training can fit into this process.” In 2021, they hosted Clay Carmouche, then Narrative Director at XBOX Publishing.

The post-doctoral fellows who help lead individual projects are also key to JapanLab’s mission. “Not that many Ph.D. programs actually train people in digital humanities,” Clulow says. “They talk about it, but they don’t actually do that much of it. So we’ve recruited two post-doctoral fellows, Megan Gilbert and Jessa Dahl, and helped them develop these projects and improve their digital humanities skills. The whole point is to help train up the next generation of professors, who can carry this template to other universities.”

That effort has proved even more effective than expected — Dahl, one of the lab’s inaugural fellows, has accepted a tenure-track professorship only one year into her two-year fellowship. Now JapanLab hopes she’ll start a similar program at her new university. “We want to spread this model all across the country,” Clulow says.

Before it takes on the nation, though, JapanLab has its sights set on expanding at UT. It already provides course development grants to faculty working in Japan studies, Cather says, and the project is looking to expand into other fields with additional funding. The through line is a constant emphasis on the digital humanities. In Cather’s course “From Genji to Godzilla,” for example, she encouraged her students to turn in digital projects in lieu of more traditional assignments. One team of students surprised her with a virtual reality game that puts the player on the street in Tokyo, staring up at Godzilla, paired with an analysis of the role of perspective in American and Japanese Godzilla films.

“It really goes back to the question of ‘why video games,’” she says, describing the excitement and energy the students put into their project. “This is what we’re trying to do, to bring Japanese studies at UT into the 21st century.”

The video game format also provides students with opportunities to engage with challenging content in a deeper way. In fall 2023, for example, a team of students led by Cather will be tasked with developing a game themed around Japanese censorship, and other recent projects have wrestled with modernization and wartime propaganda.

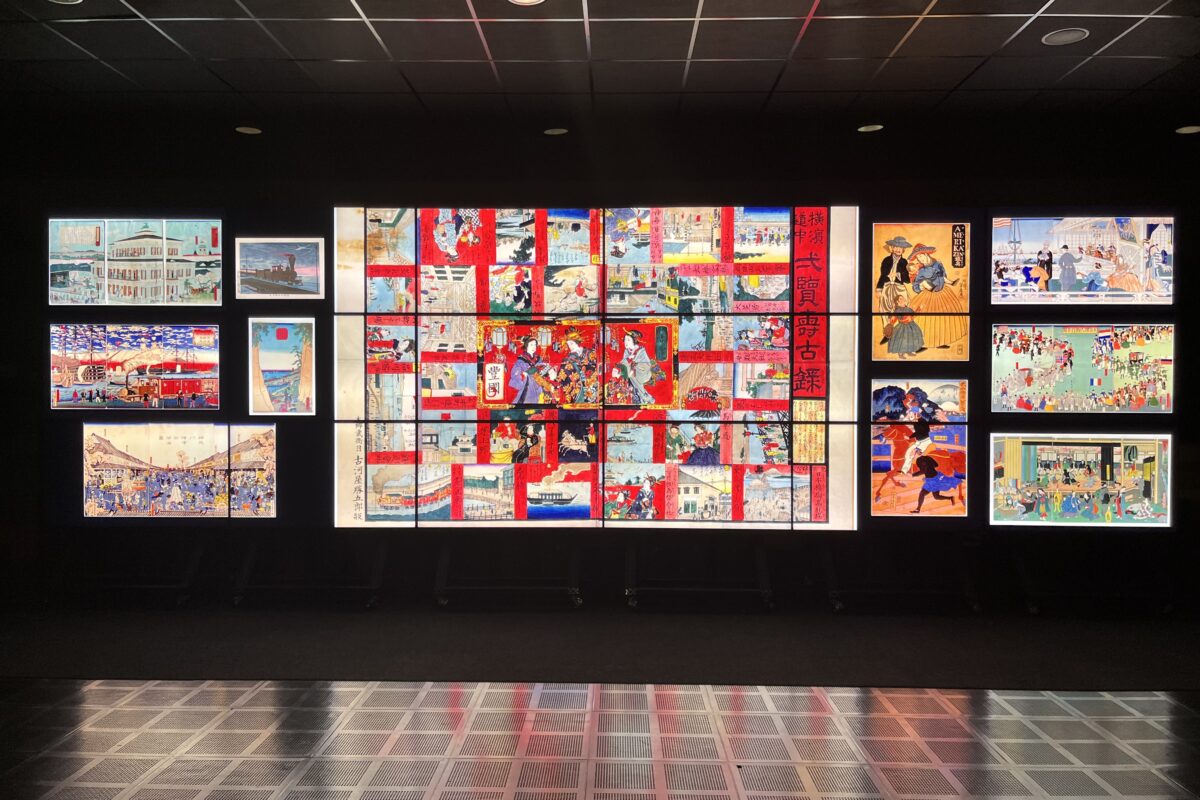

Some of JapanLab’s most thematically challenging projects have been released as digital sugoroku, a historically popular Japanese board game format similar to Snakes and Ladders. The first of these projects, Ready, Set, Yokohama!, is a modern version of a much older game. It takes players on a tour of the early Meiji period, when Japan was modernizing at break-neck speed, and includes the original game’s woodcut illustrations while incorporating text that explains the dramatic changes present in each square.

Ravina’s spring 2023 “Playing at Empire” project also uses the sugoroku format — though he was surprised at the game his students chose to update.

“I was ready for my team to work on a game from the 1905 Russo-Japanese War,” Ravina says, “and instead they chose this unbelievably difficult example from a Japanese women’s magazine meant to rally the family for the Japanese invasion of China. I told them, ‘Do you realize how hard it’s going to be to strike the appropriate tone when we know the real story that’s being so carefully sanitized in this game?’ But they wanted to step up and understand how wartime propaganda actually functions, and I’ve been really impressed with their work.”

It’s clear that the students involved in JapanLab projects are also impressed at what they can achieve. One student described working on Ready, Set, Yokohama! as “my happiest time as an undergraduate student,” and multiple students from previous projects attended this spring’s JapanLab expo, eager to see new projects and show off old ones.

That’s exactly what Clulow, Cather, and Ravina want to see. “We really want UT to be this beacon of light as to how to do this,” Clulow says. “There’s a real intimidation factor with digital humanities, where people think it’s going to be too difficult to reconfigure a course to have a digital humanities assignments, or it’s going to be too difficult to have students do a video game or a full website or even a timeline. But this is all designed to show you that it’s not that difficult, that students really get into it, and that this produces incredible results.”

“We talk a lot about ‘What Starts Here Changes the World,’” he continues, “but we truly believe this is the future of humanities education.”

Back in the visualization lab on that April afternoon, the Yokohama street scene faded from the screen, then was quickly replaced by the “Playing at Empire” sugoroku as another group of students rotated towards the podium: It was their turn to present. Volunteers were called up from the audience to act as players rolling digital dice, and the game began.