Faegeh Shirazi Weaves a Career in Cultural Textiles

Faegheh Shirazi is a woman of many worlds and eclectic interests. She speaks with a soft and lyrical Farsi accent. She is perfectly coiffed and pearled. She dances Zumba for an hour every day. After meeting her for the first time over Zoom I somehow felt like I had just had dinner with a fabulous old friend.

Despite some of the very serious subjects she researches, the professor of Middle Eastern Studies approaches her work as if it’s the combination of fun and difficult experiences that makes for a rich life and they should all be treated with joyous reverence.

Shirazi grew up in Iran in the 1950s and ‘60s with an interest in science and a plan to go to medical school. When she didn’t pass the government-mandated entrance exam, and was instead funneled to nursing school, she quickly realized that she “didn’t like blood or dead people.” So, she embarked on a new plan of studying microbiology in the United States and made her way to UT Austin, where she had family nearby. Again, she quickly learned this wasn’t the right path. “I couldn’t be cooped up in a lab looking at a microscope for the rest of my life. I realized I wanted to be in a science that was somehow related to art,” she said.

At that time, UT’s interior design department was part of the School of Home Economics in the College of Natural Sciences, and with its curriculum that allowed for a combination of science and studio art classes, peppered with some architecture and mechanical engineering, something finally clicked.

Shirazi eventually finished her undergraduate degree in interior design at the University of Houston and went on to get a master’s degree in textile science from Kansas State. “In that program, we all had to take one course in the history of textiles, and that changed my life,” she said.

She followed her new spouse to his job at The Ohio State, where she enrolled for her Ph.D. in textiles and clothing, focusing more closely on cultural textiles. She began to explore how material culture is practiced in the Muslim world.

“I never regretted hopping around,” she said. “If I had stayed in Iran, I would have had to be a nurse. Here, I was lucky to be able to try things out. Plus, my field is tiny, so I’ve really been able to forge a path and be one-of-a-kind.”

Shirazi’s focus as a researcher has primarily been on gender and women’s studies in material culture and how it relates to politics and Islam. She has been particularly interested in how Islam is sometimes practiced as a popular culture rather than as a religious one. In the Muslim world, for instance, textiles are often far more than just the materials out of which clothing is made. They are objects of great political and cultural significance.

Her latest book, Islamicate Textiles, released this past May by Bloosmbury, is all about the interwoven historical and cultural threads that fabrics hold. When I ask her for some examples to put these ideas in context, she describes the heavy role of ritual and material culture in Shi’i Islam. One of Shi’i’s biggest annual observances marks a great battle over Karbala in Iraq in 680 CE, where the armies of the Sunni kalif clashed with the armies of the Imam Husyan, the grandson of the prophet Mohammad. The Shi’is suffered a massive defeat, and Husayn was beheaded. The holiday, called Ashura, theatrically replays the events of the battle and many rich tapestries and banners are made for the month-long occasion of mourning. The banners are adorned with different colors and patterns based on the rank, level of bravery, and death of each character in the story they depict. The history of who’s who and what happened is all retold in the textiles.

Another example: In Pakistan, there are several holidays where people visit the shrines to honor the saints. Those who can afford it make a chadar, a spread or shawl, to cover the tombs of the martyrs. People get competitive about who has the best one, and they stack them on top of each other until the tombs are piled high. The prime minister makes one, famous Hindu and Muslim actors make them, and they all make a show of traveling and carrying them to the shrines. These textiles and their associated practices are status and class symbols; they are ambassadorial acts, holding much more than just colors and patterns.

One of the broadest examples of textiles illustrating politics writ large is Western colonialism, Shirazi explains. The colonial world captured many textiles from the nations it dominated. The British and the Dutch in particular infiltrated Indonesia and Malaysia. The Dutch, for instance, took wax cloth from Indonesia, mechanized its production, and then sold it in Africa, producing it with African-style patterns and designs, profiting immensely without acknowledging the cloth’s origins in Indonesia. Africans to this day call that cloth Dutch wax.

Similarly, English chintz fabric derives from India, its name a bastardization of the Sanskrit word citra (or chitra), which referred to the place it was originally produced in. The British liked the block prints so much that they industrialized its production, and it became so popular that they used it for wallpaper and women’s clothing. With this popularization, however, also came political aggression; the British forbade the Indians who made it from immigrating to England, lest the British face economic competition. The French, who made wool, also took to the fabric, and they feuded with the British over it. The whole situation became so acrimonious, in fact, that for 12 years, chintz was banned in France and authorities could literally tear it off women’s bodies in the street.

Another aspect of Shirazi’s work, which bears deep personal ties, is veiling culture. Veiling culture is now at an inflection point, particularly in Iran, so much so that Shirazi’s first book, The Veil Unveiled, written some 20 years ago, is still selling.

“I wrote that after the revolution when I was still traveling back to Iran every summer in the early 2000s. I saw how the government went to every length to reinforce the idea of wearing a veil,” said Shirazi. “Khomeini never required people to wear the hijab, just said it was preferred, but once it started being enforced, it was suffocating.” Cultural terminology came out of that enforcement. A “bad hijabi,” translated to a woman who wore the hijab improperly, who didn’t wear her veil in the right way, or whose garment was too tight. The youth didn’t want to wear the hijab.

But Iran really has a history of almost 100 years of tension between women and government over clothing and women’s rights said Shirazi: “Women have always been fighting the hijab.” In 1936, four decades before the revolution, the first Pahlavi Shah (Reza Shah) — the last ruling family of the Iranian royal dynasty — implemented a rule removing the hijab; it forced an unveiling policy known in Iranian history as the kashf e hejab era. “My mother lived through that era and was young then,” she remembers. “My mom remembers my grandmother not walking outside for three years, because the authorities would rip the hijab off, and she wanted to keep wearing one. Women felt literally stripped. My grandmother and her friends used to meet up on the rooftops and would jump roof-to-roof to see each other without going out in the streets. This was women’s resistance.”

The second Pahlavi dismantled the forced unveiling, and that’s when Shirazi came along. Then, with the revolution in 1978–‘79, veiling was again implemented as a rule, and has continued since, but with some confusing rhetoric added to the mix.

“They added an amendment to the constitution to make it seem like women are freer than they are. It now discusses women and sounds great, but it’s all lip service. Women can vote, but the government eliminates anyone they would want to vote for. Even women sitting in parliament might as well be men in a scarf. Men decide for women,” said Shirazi.

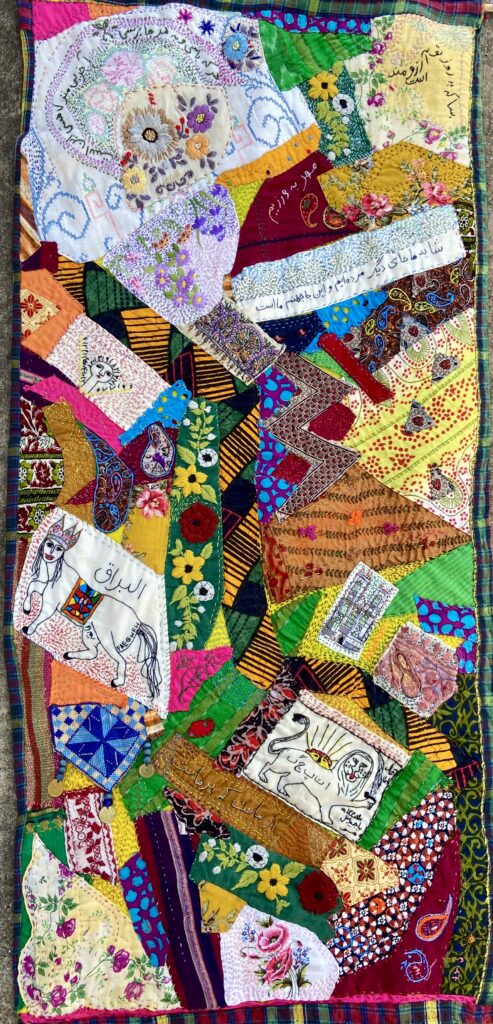

Shirazi has enjoyed the freedom to explore all these ideas openly in her research — without the eye of a government censorship committee watching over — and also in her own painting and textile work, into which she incorporates Persian calligraphy, vibrant colors, visible brushwork, embroidery, and scenes of crowded cities in the Middle East. “The joy of painting for me is about combining colors. My painting is figurative, and I most like to paint cats and build my own cities and buildings. My buildings are vivid memories of what I have seen,” she said. You can see the fusion of her interests in her works, and how she has layered upon themselves to form her own kind of patchwork of scholarship.

Shirazi, who has managed to convince all of her publishers to use her own art on her book covers, retired from teaching just this August, 2023. Her research and writing will continue, however. Just more time for Zumba, and making art, and music lessons on traditional Iranian instruments. “Maybe after that, I’ll learn Spanish,” she said. “This is really my time of freedom. Anything that brings you joy; you should do it.”