Steven Hoelscher, professor of American studies and geography at UT and faculty curator for photography at the Harry Ransom Center, discovered his scholarly passions thanks to two travel-related revelations. The first came as an undergraduate, when he studied abroad in 1980s Vienna, a city on the edge of the Iron Curtain still wrestling in fascinating ways with the living legacy of World War II.

“That’s when I changed,” Hoelscher says of his semester in Austria. “Everything changed. I went from being a biology pre-med major to a historian-geographer. It opened my mind to the effect of place and the depth of historical places on people.”

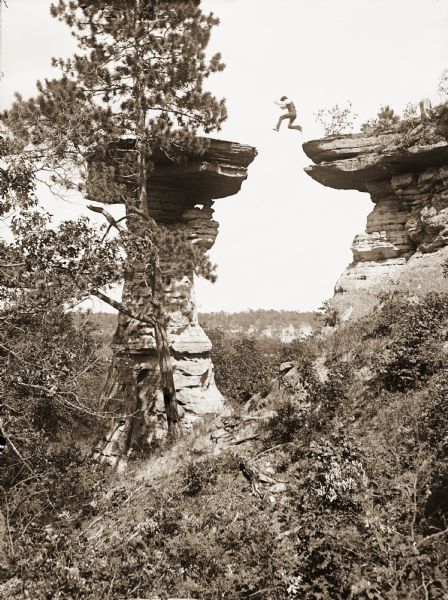

Hoelscher’s next transformative moment of academic self-discovery came on more familiar ground — in Wisconsin Dells, Wisconsin. Hoelscher grew up in Minnesota, vacationing in Wisconsin with extended family every year. In the winter of 1993, as a Ph.D. student at the University of Wisconsin-Madison, Hoelscher drove out to the vacation town of Wisconsin Dells in the deep off-season. Exploring the town, he knocked on the door of an old photography studio that had once belonged to H. H. Bennett (1843-1908), a regionally preeminent photographer of landscapes and portraits of Native American subjects.

There, Hoelscher met Bennett’s granddaughter, who at the time was still running the photography studio and shop. “I went in there just wanting to learn a bit about this photographer, and I was presented with all sorts of documents that make historians and historical geographers like myself really excited,” Hoelscher says.

That thrillingly unique and previously unexplored private archive — including Bennett’s letters, glass plate negatives, business ledgers, and records of his efforts to learn the local language of the Ho-Chunk people he photographed — would eventually form the basis of Hoelscher’s 2008 book Picturing Indians: Photographic Encounters and Tourist Fantasies in H. H. Bennett’s Wisconsin Dells. It also turned Hoelscher into a specialist on historical photography.

“Nobody had really worked through those materials before,” Hoelscher says of Bennett’s studio archive. “That’s what was really exciting for me. And it made me realize that, to understand the role of these photographs in shaping this place, I needed to understand much more about photography. I had to get deep into the photographic canon. I became more and more interested in photography as a way to understand historical and geographical processes and patterns.”

Picturing Indians was not an easy book to write. Fifteen years passed between that fateful midwinter encounter with Bennett’s papers and the book’s 2008 publication with University of Wisconsin Press. In the intervening period, Hoelscher published two other books — Heritage on Stage: The Invention of Ethnic Place in America’s Little Switzerland, his dissertation project on another culturally complex corner of small-town Wisconsin, and Textures of Place: Exploring Humanist Geographies, a survey of essays he co-edited that explores key themes in the modern discipline of geography. He also published dozens of essays and book chapters in this period on topics ranging from “Making Place, Making Race: Performances of Whiteness in the Jim Crow South” to “The Photographic Construction of Tourist Space in Victorian America.”

All the while, Picturing Indians was gestating. One reason it took so long is that, after spending extensive time poring over Bennett’s materials, Hoelscher began to realize that telling just Bennett’s side of the story would not be enough. He had to find a way to excavate the perspective of the members of the Ho Chunk Nation of Wisconsin (sometimes also known as the Winnebago), who were paid photography subjects, pawnshop clients, and trading partners with Bennett as he used their images to mythologize the past and present of Wisconsin Dells for regional tourists and for the wider market of consumers of American popular photography Hoelscher writes early in the book:

“What H. H. Bennett’s Ho-Chunk pictures show about nineteenth-century white perceptions of Native Americans, about social tensions in a volatile American region, and about Native efforts to make a better world for themselves bears a close relationship to what they hide: federal policies of Indian removal, centuries of mutual distrust, and creative responses to novel situations. If a picture really is worth a thousand words, we must be careful to attend to all the voices speaking these words—to listen to all its stories, even if some of those stories are barely audible.”

Already in possession of a once-in-a-lifetime trove of primary sources from Bennett, Hoelscher determined to double down and develop his own documentation on the Ho-Chunk perspective. Over two winters, he met with local Ho-Chunk groups, talking to them about their perspectives on Bennett’s photos and their thoughts on his records of his attempts to learn the Ho-Chunk language. He scoured primary sources for quotes from 19th-century Ho-Chunk people, finding, for instance, evidence of the refusal of two men to wear a culturally inappropriate “Apache war bonnet” for a staged photograph in Bennett’s studio. Hoelscher also dedicates several pages of his epilogue to a discussion of the contemporary Ho-Chunk photographer Tom Jones, who responds to Bennett’s work in interesting ways. “It turned out to be fundamental to the book in a way that I would not have necessarily anticipated,” Hoelscher says of his work integrating the Ho-Chunk point of view.

Though Bennett was not the most egregious romanticizer and falsifier of Native American life during his epoch — he fares relatively well in comparison to rival photographers who simply had white people pose in Native American costume — Hoelscher is critical of Bennett’s subtle promotion of the myth of the “vanishing race.” This myth, crucial in the late 19th century and still prevalent today, prefers to portray people like the Ho-Chunk as “elements of a fast-disappearing landscape,” “outside the stream of history,” and “more aligned with pre-Columbian nature than Gilded Age culture,” in Hoelscher’s words. Photographs that traffic in this myth, believes Hoelscher, elide the ongoing catastrophes, bitter hardships, and complex survival strategies that animated Ho-Chunk life in the era of their production.

Hoelscher’s project in Picturing Indians is to restore a more complex sense of late-19th century reality to Bennett’s mythical photos and to begin to trace the story of Ho-Chunks as protagonists in the pictures. As Chloris Lowe Jr., twice-elected leader of the Ho-Chunk Nation, tells Hoelscher, looking at a photo of a 19th-century man named Chach sheb-nee-nick-ah (Young Eagle): “There is a look of defiance in this photograph. This young man knows what he is doing… Here is a person who was there [in Bennett’s studio] for a reason, he certainly had his own ambitions for this photograph.”

Picturing Indians has been available for sale at state historical sites in Wisconsin Dells and in Madison for 15 years now, slowly but surely changing the conversation about the area’s history as told through its earliest photographs. During that same period, Hoelscher’s growing prominence as an authority on the geographical, cultural, and historical aspects of photography has led him to fascinating new scholarly opportunities. For instance, he returned to his early interest in the German-speaking world to produce the article “Dresden, a Camera Accuses: Rubble Photography and the Politics of Memory in a Divided Germany” (2012), in which he unpacks the legacy of famous photos of the mercilessly firebombed city. As Hoelscher demonstrates, these images have been used in different ways by the postwar East German state and the contemporary political left and right in today’s united Germany. Also, in a rare research coup, Hoelscher wrote for Smithsonian Magazine in 2019 about discovering a lost essay by Langston Hughes in the archive of an obscure investigative journalist. Hoelscher contributed scholarly context for the essay’s production alongside a first printing of the essay for an American audience.

That incredible find was an outgrowth of Hoelscher’s new role at UT’s Harry Ransom Center (HRC) as faculty curator for photography. Perhaps the most enviable project Hoelscher has worked on in recent years is another HRC affair: the gorgeous photo book Reading Magnum: A Visual Archive of the Modern World (2013). In 2013, HRC acquired an archive of over 200,000 photographs from the Magnum photography cooperative, a globetrotting 20th-century photojournalism agency co-owned by its creative collaborators, including the legendary Henri Cartier-Bresson and Robert Capa. Famous photos included in the archive include Capa’s images of the storming of Omaha Beach on D-Day and Stuart Franklin’s image of a single protestor standing down a line of tanks in Tiananmen Square in 1989. “It’s a foundational photo archive,” Hoelscher says. “All you have to do is open up any history of photography book, and there they are.”

In the excitement over the acquisition, Hoelscher proposed that HRC put together a book to, as he puts it, “open up the archive for scholars to take a look at what’s in there, and then share their insights.” Hoelscher himself provided the introduction, in which he proclaims the Magnum photos, which touch on so many important news stories and key social themes of their era, from the Vietnam War to mass immigration to celebrity culture to the postwar reconstruction of Europe, “the raw material from which collective memory is constructed.”

In the end, he settles on the phrase “progressive sense of place,” which, he argues, “by its very definition, links to places beyond, all the while maintaining its distinctiveness.” Hoelscher writes:

“That same geographical imagination also recognizes how dynamic places are, how they are forever under pressure to change…. It’s a way of thinking about the world that recognizes the porous nature of the inside and outside, which makes it harder to render judgments about insiders and outsiders. Finally, a progressive sense of place acknowledges that places do not have single unique ‘identities,’ but that they are packed with internal differences and conflicts.”

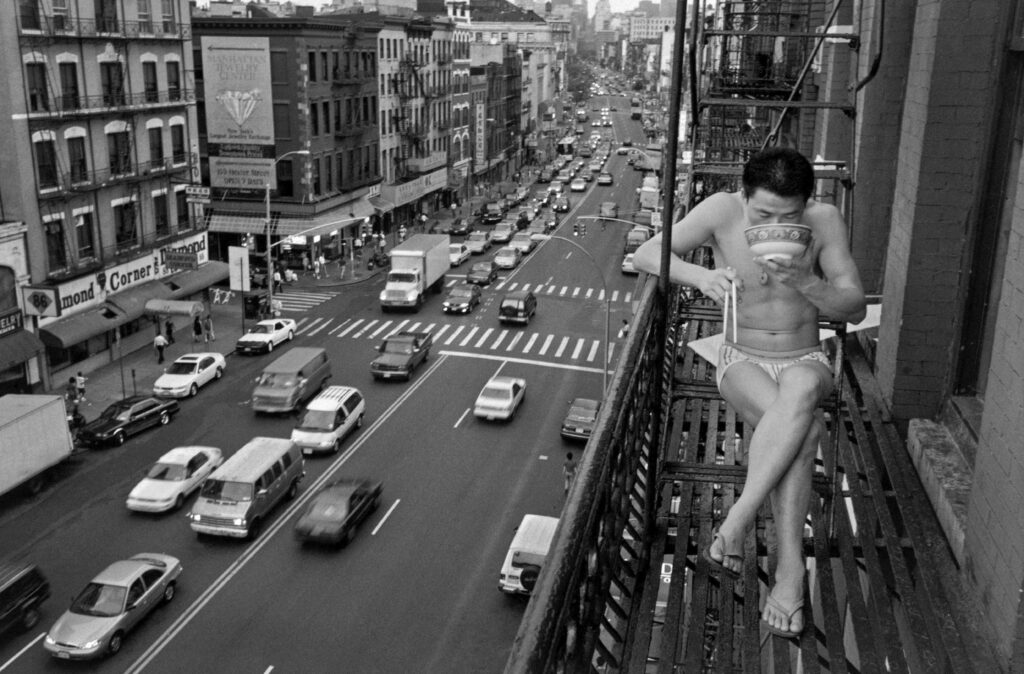

In addition to selecting which photos to include in the book and how to arrange them by theme and collection — a task he describes as “just so fun” — Hoelscher also contributed a critical essay, “Magnum’s Geographies: Toward a Progressive Sense of Place.” This chapter encapsulates much of Hoelscher’s recent thinking on the power of photography to impact geography, which is to say, the role that an artist’s image-making vision can play in forming a community’s sense of where we live or visit. Exploring photo series like George Rodger’s 1949 images of the Nuba people in Sudan, Paul Fusco’s 1968 images of Robert Kennedy’s funeral train, Elliott Erwitt’s 1957 “sneak photography” of Soviet Union public spaces at the moment of the Sputnik launch, and Chien-Chi Chang’s photos of Chinese immigrants in the U.S. from the 1990s and 2000s, Hoelscher endeavors to identify a consistent way of interacting with place that pervades all or most Magnum photos.

This sort of cosmopolitan, ephemeral, and open-to-contradiction vision of place is in many ways the opposite of what Hoelscher had examined in Wisconsin Dells and the work of H. H. Bennett, who sought to reify a timeless idea of a Native past that was portrayed as unrelated to contemporary reality. “A progressive sense of place is really pushing against a tradition that somebody like Bennett would embody, of a more traditional, insular, cloistered sense of place,” Hoelscher says.

What links the two book projects is Hoelscher’s own eye, on the one hand celebrating Magnum for its progressive way of being in the world and on the other hand laboring to provide a scholarly corrective to Bennett’s limited, even intentionally blindered vision. Wherever he lands in his wide-ranging studies and travels — and he’s now back to spending time in Vienna, leading UT’s summer study abroad program there, opening up the minds of young students like he once was — Hoelscher brings to

bear that well-trained eye for place, image, and underlying textures and complexity calling out for scholarly analysis.

As Hoelscher writes in Reading Magnum, paraphrasing his beloved Cartier-Bresson, who denied that his “wandering camera” sought to nail down any broad, definitive statements about the places it captured: “The world is too complicated for a general picture.”