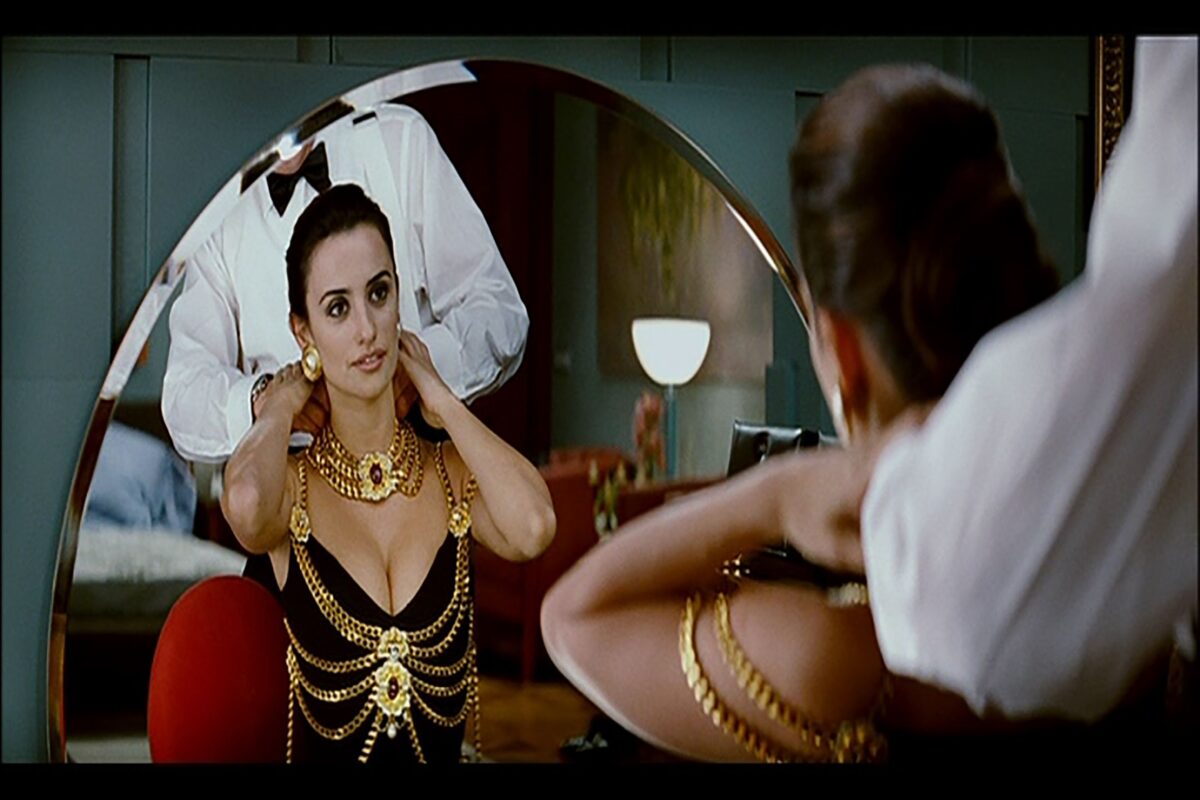

The origin story of Jorge Pérez’s book Fashioning Spanish Cinema: Costume, Identity, and Stardom takes place in a Kansas City movie theater in 2009. As Pérez watched Pedro Almodóvar’s Los abrazos rotos (Broken Embraces) on the big screen for the first time, something grabbed his attention: Chanel. Lots of Chanel. The film’s protagonist, played by Penélope Cruz, wore not one but three outfits by the iconic French fashion house.

“They’re so prominent and so visually stunning,” says Pérez, professor and chair of the Department of Spanish and Portuguese at The University of Texas at Austin. “When the movie finished, I was on another planet. I didn’t want to go back to reality. I started making connections to previous movies by the same director that also used the Chanel brand. I thought, ‘This is not coincidental. There’s a pattern here. Why is he using the same designer? What is the meaning of this?’”

As Pérez dove further into researching the use of fashion in Almodóvar’s films, what he originally envisioned as an academic article quickly grew into a book chronicling almost 100 years of costume design in Spanish cinema.

Pérez approaches costume like an art historian discussing symbolism in painting. This is most notable in his exploration of Chanel, to which he devotes a full chapter. The brand is heavy with associations in the post-Franco Spanish society in which Almodóvar’s stories unfold — the clothes signal a kind of mature respectability but are also a mark of status in a country coming to terms with consumerism and modernization. Chanel’s specific meaning, as Pérez interprets it, changes between films. In one film, a character with a complicated relationship with her mother wears a Chanel suit to convey her standing as a sophisticated adult. In another, a transgender sex worker dons a knockoff Chanel outfit to project respectability and femininity. That the garment is an imitation rather than a “real” Chanel introduces themes of authenticity and questions whether such qualities are innate or rather crafted through the performance of social roles.

“Sometimes the costumes can really take on a prominent role and have autonomy and call attention to themselves almost like a protagonist,” Pérez explains.

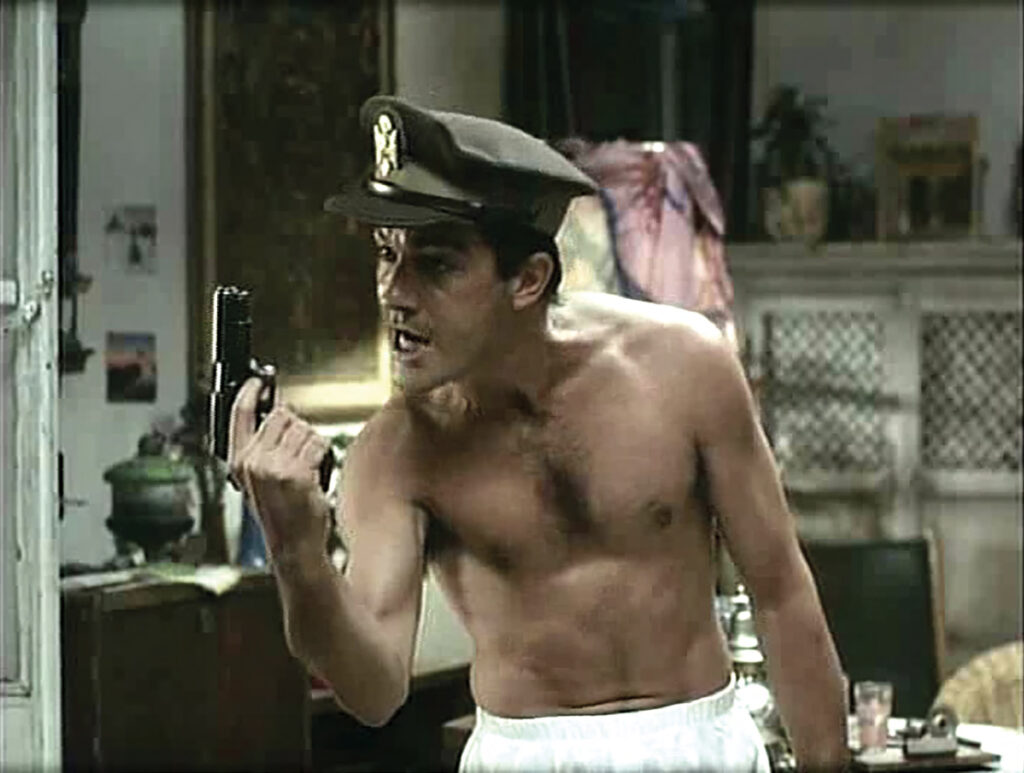

Clothing can also be a lens through which to observe broader social trends. In a chapter about the changing depiction of men’s undergarments in film, we learn that the sight of Antonio Banderas in boxer shorts in the 1989 film Bajarse al moro (Going Down in Morocco) sent Spanish audiences into fits of laughter. Banderas, who soon after would be crowned People magazine’s “sexiest man alive,” was carrying on a long tradition in Spanish comedy — looking foolish unclothed in order to uphold masculinity. Traditional gender roles were still rigidly enforced by the authoritarian Franco regime during the mid-to-late 20th-century heyday of Spanish comedies. Women could be portrayed as objects of sexual desire, but men were to be seen as providers and heads of households. Filming unclothed male characters with any hint of eroticism was perceived as feminizing. A man in goofy, deliberately unsexy underwear, on the other hand, was safely masculine. Additionally, the outerwear of the traditional male had become so serious and monochromatic that stripping away that protective layer to reveal unflattering white boxer shorts was easy comedic fodder.

The scene was even more complicated, notes Pérez. This use of undergarments revealed a national feeling of aesthetic inferiority to the archetypal Northern European man — a taller, more cosmopolitan gent who favored colorful, form-fitting briefs — but also a sense of moral superiority. Spanish characters were traditional family men, after all, not frivolous playboys.

As Spain transitioned into a modern democracy, however, old-fashioned ideas about gender were gradually relaxed and costume designers for various film genres began dressing and undressing male actors with more style. If anything, comedies lagged behind in the fashion revolution (Banderas was already playing dapper leading men when he gave his comical boxer performance). By the early 1990s, Spanish cinema had graduated to the unsubtle sexualization of Javier Bardem playing an underwear model in Jamón, Jamón, and today’s male actors are not just allowed but expected to be fashionable in both under- and outerwear.

Pérez notes that the drabness of male clothing and the lack of attention paid to the contribution of costume design in cinema are connected. Once men adopted the uniform dark business suit in the late 19th century, fashion was relegated to the realm of female concerns.

“Fashion is demoted and really decried as something shallow or feminine,” he says. “Those are gender asymmetries that we’ve had throughout history of associating anything feminine with something superficial, not intellectual enough, not artistic enough. Those are hang-ups of our society, but luckily things are changing and male fashion is becoming more and more important.”

Throughout the book, Pérez strives to elevate the status of costume design in film, which he describes in his introduction as the “ugly duckling of the industry.” While some critics feel the sole purpose of clothing in cinema is to accurately reflect characters and settings without drawing attention to itself, Pérez sees it as a critical element of storytelling. Each chapter of Fashioning Spanish Cinema aims to bring fashion into the foreground of film studies.

The book concludes with an examination of how actors’ offscreen use of fashion helps them attain stardom, and Pérez’s next book will focus on celebrity culture in Spain. He’s currently poring over the styles of not just actors but also professional athletes, politicians, and even the queen of Spain. Basically, anyone whose success depends on creating and maintaining a brand.

“Obviously, I’m having a blast,” he says. “This doesn’t even feel like a job.”