Part I: The Scholar

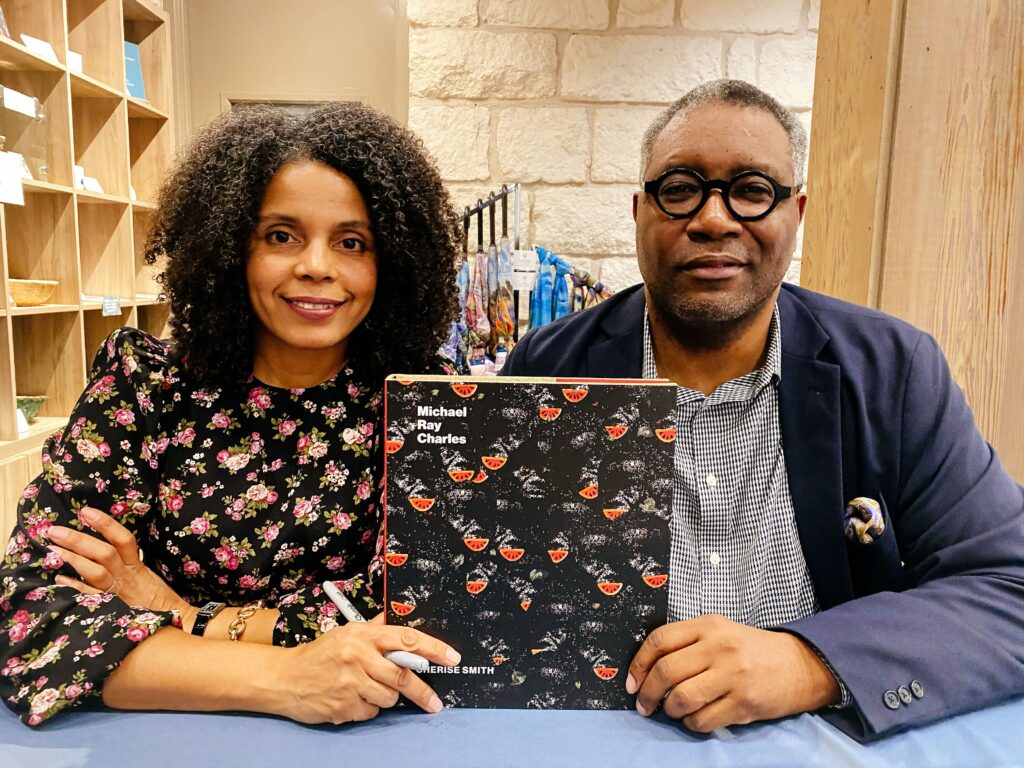

Cherise Smith didn’t set out to write what became her second book, the award-winning Michael Ray Charles: A Retrospective. Instead, she agreed to write one essay for an edited volume on Charles, one of the major Black American artists of the past few decades and now a professor at UT Austin.

“I thought it would become a chapter in my next book,” says Smith, who is chair of the Department of African and African Diaspora Studies and Executive Director of the Art Galleries at Black Studies. She wrote the single essay, submitted it to University of Texas Press, and then nothing happened. The book, it became apparent, wasn’t going to come together. Too many moving pieces. UT Press decided to shelve the project.

Rather than just fold the essay into her next book, as she’d planned to do anyway, Smith paused. She had been thinking seriously about Charles’s work since she first encountered it, in the late 1990s, and she had been a friend and collaborator of his since he first helped recruit her to UT as an assistant professor. In writing the essay, she’d already done the foundational work of laying out the key themes and milestones in Charles’s life and career. Maybe there was an opportunity, she realized, for something more.

“I got in touch with the press, and said I have an idea,” says Smith. “I think I can do this book, but it’s going to be my book. It’s not going to be his book. It’s not going to have different small pieces written by other scholars. I have a more substantial story to tell.”

Smith’s confidence was persuasive, and soon both UT Press and Charles, who was by that point teaching at the University of Houston, were on board. After further research, and a series of long interviews with Charles, Smith expanded the essay into a book-length manuscript, took charge of having Charles’s work photographed, and oversaw the design of the lavishly produced book. She worked closely with the artist during the process but was clear throughout that it was her book about him, not their book.

“He would occasionally ask, ‘Can I read what you wrote?’” and I’d say no. “I don’t sit with you in the studio while you’re painting.”

Charles was able to read the book only after it was in a close-to-final draft form. “Initially he was a bit grumbly about the things he thought I didn’t have right,” Smith remembers, but eventually he came around. “I think he was impressed with the book, and the substantialness of it. This is a real history, and to that point he hadn’t had a real history written about his work.”

Charles concurs: “I had to let go. It’s Cherise’s book, and I’m comfortable with her surmise of what I’m doing. In the end, she was the perfect person to speak clearly about my work, and to contribute her own creativity and intelligence to the value of what I’ve been doing.”

Michael Ray Charles: A Retrospective was published in 2020. It’s a gorgeous book, with nearly a hundred full color plates of Charles’s work. In it, Smith lays out Charles’s biography, closely tracks the development and evolution of his ongoing exploration of the history of stereotypical representations of Black people in America, and situates him within the larger realm of American and African American art.

Part 2: The Artist

Michael Ray Charles was visiting a museum in Germany, some years back, when he found himself alone in a gallery with a Rembrandt. He got up really close to it, inches away. “There was no one there to tell me not to,” he remembers. He was so close, he says, that he was able to discern the particular physical motion that Rembrandt had made, 400 or so years prior, to effect one of the brush strokes. “I could tell you the flick of the wrist he used,” he says. “It was still alive.”

The ways in which the past lives in the present, and the mechanisms that artists use to make the past visible, are at the heart of the work that Charles himself has been doing over the past few decades. A key moment in his development came in 1992, when a fellow classmate in the University of Houston MFA program gave him a small plastic figure of a Black person (maybe a child) with stereotypically exaggerated features.

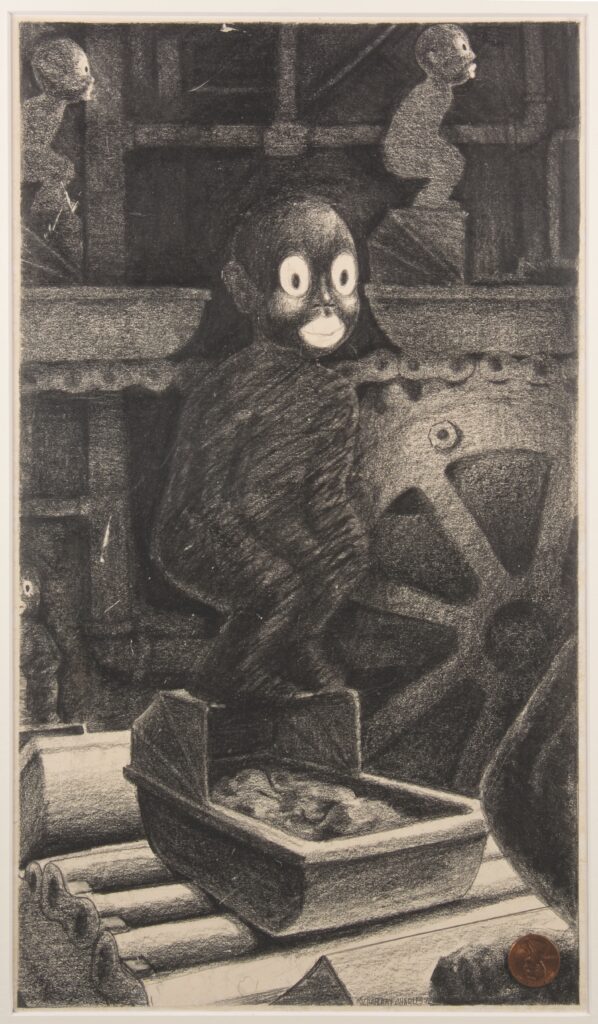

“Composed of plastic material, the waxy black figure tops out at about five inches tall,” writes Cherise Smith in her book Michael Ray Charles: A Retrospective. “It bends at the knees in a seated position, hands resting on the tops of thighs. The figure’s unnatural face appears more simian than human, its eyes and mouth open wide to form O’s.”

The figure became the key image not just in Proudly Man-u-factured in the U.S.A., one of the first pieces that Charles did in what is now recognized as his mature style, but a recurring image in his work over the decades, appearing in various forms in paintings and installations. His treatment of it — making visible and visceral its construction, and heightening and playing with its stereotypicality — also became a template for how he approached and rendered the world through his art.

“Charles found a ready-made object from popular culture, altered it for his uses, and deployed it in a different context, thereby complicating its meanings,” writes Smith, who is Chair of the Department of African and African Diaspora Studies in which Charles is a professor. “The drawing also demonstrated the artist’s meditation on how stereotypical meanings are manufactured. Finally, the work, with its shadowy shading, manifests Charles’s formal reflection on the color black and discursive contemplating of Black identity.”

Once he found his method, Charles’s success in the art world was relatively rapid. He began selling his paintings while in graduate school, and was making his living as a painter when, in 1997, the film director Spike Lee came to a show of Charles’s work. Lee was sufficiently impressed that he commissioned Charles to do a painting that became the primary image in the movie poster for 4 Little Girls, Lee’s 1997 documentary about the 1963 bombing of the 16th Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama.

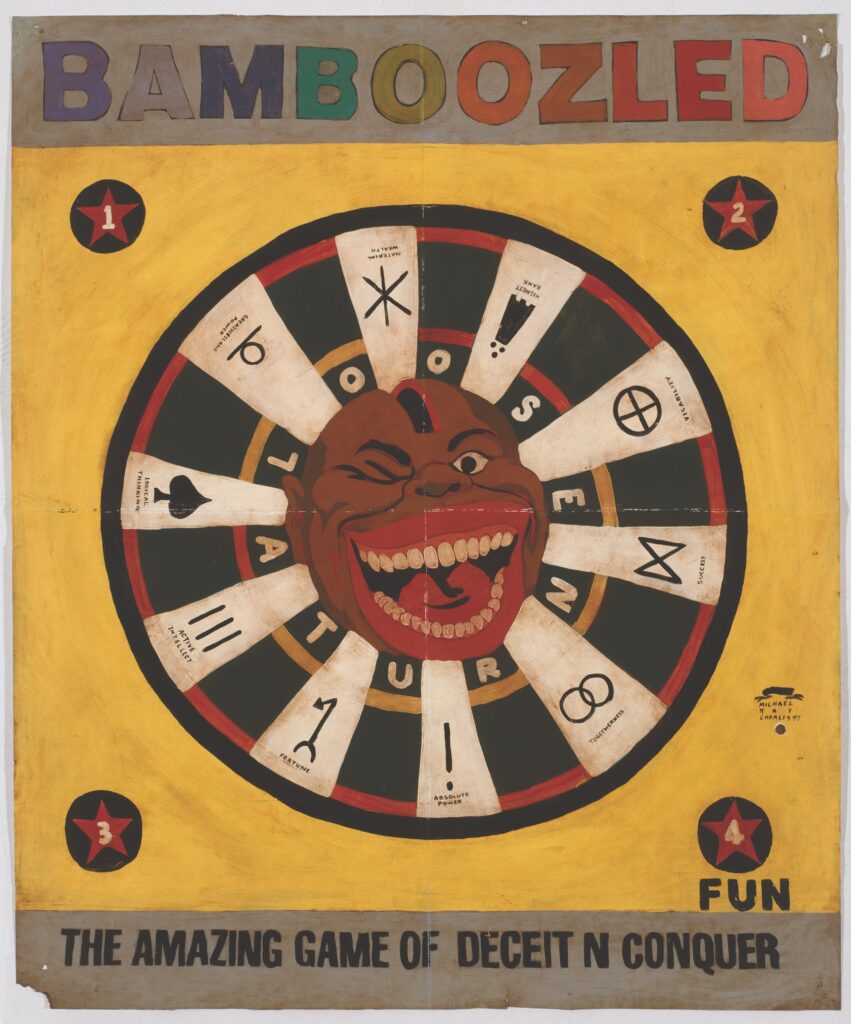

A few years later, Charles worked even more closely with Lee on the movie Bamboozled, which features both images that Charles created directly and a general visual language that was influenced by his work.

“I did a painting in 1997, or thereabouts, that was inspired by Denzel’s version of Malcolm X in Spike’s movie,” says Charles. “It was Malcolm’s stump speech, ‘You’ve been had, you’ve been took, you’ve been hoodwinked. Bamboozled.’ Spike saw the painting at my show, and then contacted me about it.”

In one of the ironies that can befall artists who have a significant influence on the culture, Charles’ work is now often emulated or copied, often unacknowledged and perhaps unconsciously, by others.

“I see some things where I actually stop and have to ask myself whether I did that,” he says. “No, I didn’t do that. But that’s fine. People complain about cultural appropriation, but I think we spend too much time worrying about that. There is so much that we share, and can share, and I’m fine with people drawing on my work when nothing egregious is occurring in any step of the imagination. It’s all cultural production.”

At the moment Charles is working a lot with the visual language of minstrelsy, which he traces back to ancient Roman theatrical imagery and then forward to our present pop culture, which is so profoundly influenced by the visual language of minstrelsy that it becomes impossible to simply treat it as an instance of racism (though it certainly can be that as well). “In many ways it was America’s first real cultural contribution to the world,” says Charles. “We call it racism racism racism, but it’s so much more complex than that.”