Walking through a greeting card aisle can be like walking through the Cliffs Notes outline of a life, starting with “It’s a Boy/Girl!” and running straight through “Condolences.” Some feel profound, giving us the words we didn’t know how to conjure; many get a tired eye-roll, even as we stock up before holidays and birthday parties. For UT anthropologist Craig Campbell, that eye-roll was the start of something far more interesting.

As an ethnographer, someone who studies and describes cultural experiences of the world, Campbell is trained to see the meaning in the things most people create or use without second thought. “The greeting card, for me, was a very natural place to begin,” he says. “Most people sort of roll their eyes at them, and to me that means there must be something interesting happening there.”

But Campbell is an experimental ethnographer, meaning that he sees the process of making a cultural artifact as a way to study it. And so, to better understand the cultural purpose and possibilities of greeting cards, Campbell became a card designer.

“A lot of my work is based on this sort of experiential knowledge,” Campbell explains. “Because if I’m going to study greeting cards, I can just study greeting cards, right? I can go to the greeting card aisle, I can interview people. But to actually go through the process of making cards is a different kind of engagement, and it teaches you in different ways.”

In 2019 he began working on “Greeting Cards for the Anthropocene,” an ongoing research-project-cum-design-collective, in collaboration with Casey Boyle, an associate professor in rhetoric & writing at UT Austin. The idea behind the cards is simple, even if their meaning isn’t. “Essentially, I want to ask the question: If there was a section for climate catastrophe in the greeting card aisle, what would that look like? What kind of cards would populate that?” Campbell says. “And now we’ve been making those cards, which then become an ethnographic device to engage people in a conversation about feelings and communication that can often be fraught and difficult.”

The project’s focus on exploring and communicating difficult emotions is fitting, considering the history of the greeting cards Campbell riffs on. When Hallmark cards first became popular in the mid-1800s, advocates argued the cards were necessary because people no longer knew how to express themselves. “They said people particularly needed help with complicated emotions,” Campbell says. “And what could be a more complicated emotion than feeling like, ‘What the hell am I going to do about climate change?’”

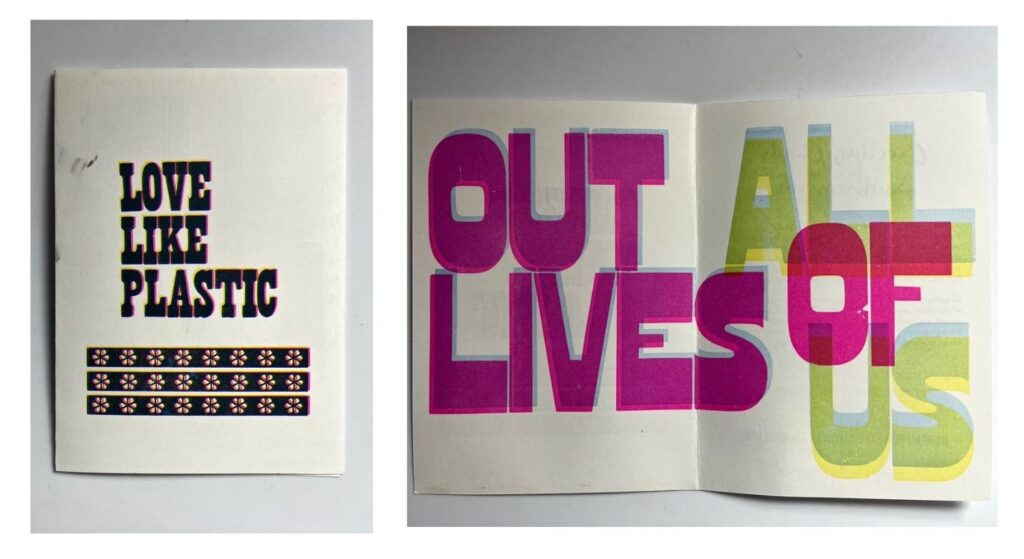

Over the last four years, Campbell and his collaborators have come up with more than a dozen greeting cards, and more are in process. Their tone ranges from cheeky to plaintive. One starts with “Love Like Plastic” before flipping open to reveal the punchline, “Outlives Us All”; another reads “You’re a Natural! Disaster,” complete with skull and crossbones. All are produced individually by letterpress, and many feature typefaces from the Rob Roy Collection of turn-of-the-century wood type, housed in UT’s College of Fine Arts on permanent loan from the Harry Ransom Center.

The combination of historic fonts and colors gives the cards a nostalgic feel, even as they grapple with wildfires, the complexities of the oil and gas industry, and mass extinction. And while “Greeting Cards” isn’t Campbell’s first design project — he was an art student for a year before beginning his degree in sociology and has some curatorial experience — it does represent an expansion of his skill and interest. His growing fascination with letterpress printing, a skill he only picked up after coming to UT Austin, is particularly essential to the project, and he’s travelled widely in search of new typefaces for printing new cards. This spring, for example, Campbell visited a studio in Estonia to work with Cyrillic font, eventually producing the project’s first Russian-language entry.

Campbell frequently collaborates to create the various designs, including with other members of UT faculty, visiting scholars, and classes of students. It’s all part of the ethnographic process: Working with others to pitch ideas or discuss font choices gives Campbell that much more material to parse for patterns and meaning. It’s even useful when students come up with the perfect phrase only to realize it physically won’t fit on a card. “Those constraints become a really productive force for having these kinds of conversations about the limitations of what you can do or say,” Campbell says.

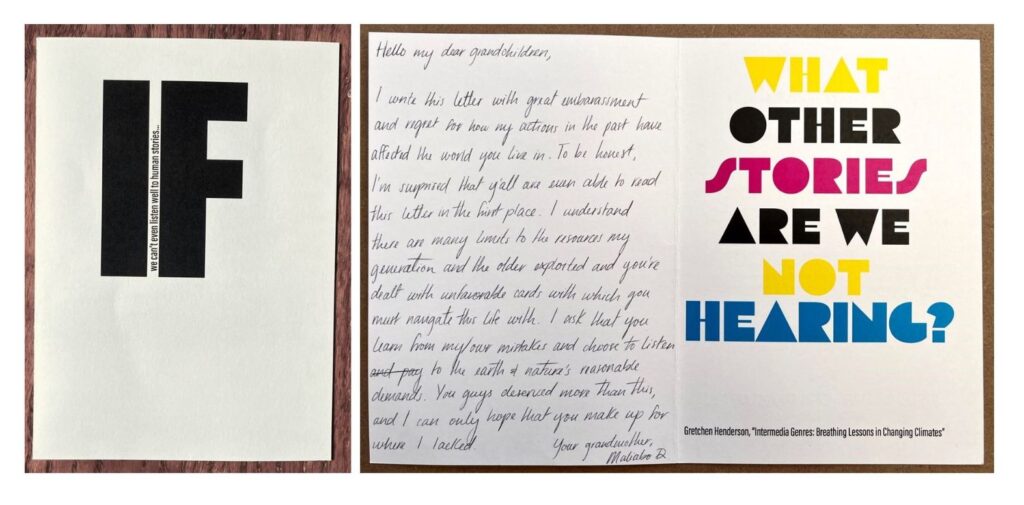

But the ultimate collaboration is that between a card and the person who fills it out, and “Greeting Cards for the Anthropocene” is as much about the experience of writing a card as it is about the process of designing one. As part of the project, Campbell regularly hosts writing parties in various public spaces, ranging from art galleries to wine bars. When participants sit down to write a card, they’re provided a placemat with information about the project and two stacks of cards. One set has suggestions on who to address the greeting card to — Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, say, or a close friend, an animal, or even oneself — and the second has suggestions on what to write about. Participants are free to swap cards or ignore them completely, Campbell says. The point is simply to get them thinking through writing.

Many participants mail their cards to a recipient, prompted or otherwise, or keep them as mementos, but others choose to leave the completed cards with Campbell to be archived. Of these, he says, the most moving are the ones that explore personal encounters with climate change.

“One of the most powerful ones was from a woman whose son was a firefighter,” Campbell says. “She was writing to him about how she felt guilt about being part of a generation that had really imbibed the consumerism that has led us to this place, but she also expressed her anxiety and fear for him as someone who was both protecting her and also paying for her sins. That sort of gives you a sense of what the project is about.”

The future of “Greeting Cards for the Anthropocene” isn’t certain — Campbell might say no future is — but he’s hard at work writing a book about the project, focusing on one card per chapter. He can see the project growing, too, either with new cards or new ways of disseminating existing designs. One new approach involved this very magazine and invited our print readers to participate in the ongoing project by filling out and mailing in a “Greeting Cards for the Anthropocene” postcard included in the fall 2023 magazine. If you didn’t receive that issue but are interested in participating, email us at colapublicaffairs@austin.utexas.edu and we’ll send you a postcard as long as supplies last. You can also learn more about Campbell’s project at www.greetingcardsfortheanthropocene.net.