When Erika Bsumek set out to make a digital timeline tool to help students in her history courses sharpen their research and critical thinking skills, she also reshaped — literally — how relationships between historical events are visualized.

Bsumek, a professor of history at UT Austin and the creator of timeline platform ClioVis, says the tool was built to encourage students to take a more active role in the learning process. In the five years since its launch, Bsumek and a small team of developers, including former UT students Ian Diaz and Braeden Kennedy, have continually refined ClioVis’s capabilities to better meet that mission.

“We all have a unique perspective that influences how we ask questions. ClioVis enables you to bring that to your projects.”

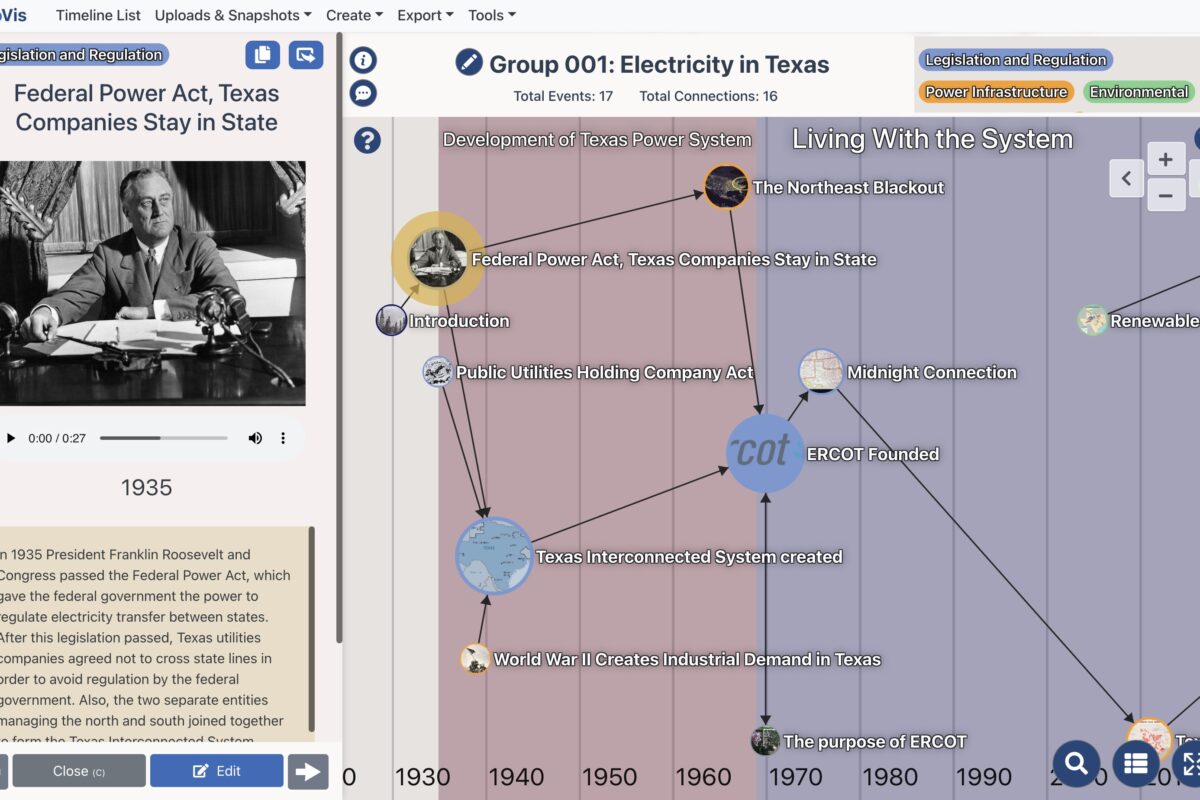

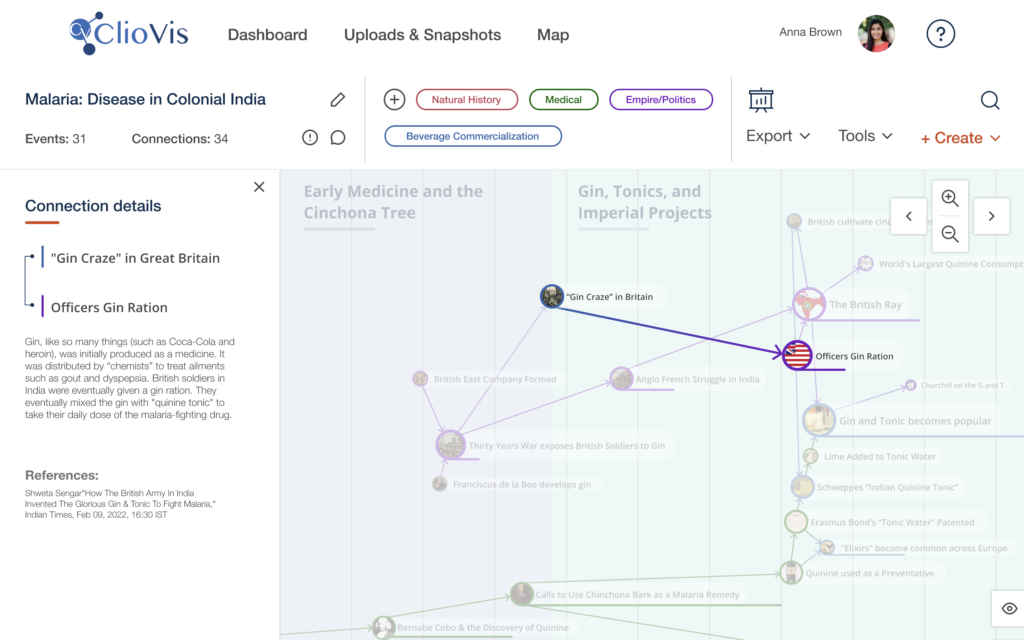

ClioVis allows students to map out projects by writing event descriptions within circular “nodes” and connecting them with arrows. But unlike most timeline platforms, ClioVis requires students to explain the connection, in writing, between two nodes.

“Other timeline tools just involve plotting things in time, but ClioVis enables you to understand the relationship, the causation or correlation, between things happening,” says Bsumek.

More than just adding context that students might overlook, this design allows for a new way of thinking about history: not as a series of chronological events, but as interconnected, complex conceptual webs. In other words, “students learn that history and scholarship are messy,” Bsumek says.

While ClioVis reflects that messiness, its design also allows for simplicity. Students can color-code each event node and filter out colors to focus on a single storyline or see how specific storylines are connected. And by requiring users to anchor their narratives with clear thesis statements, ClioVis brings students’ own ideas and perspectives to the forefront — and helps them think critically about their arguments and the evidence they collect to support them.

“The platform enables you to learn how to find sources, think with evidence, and explain relationships. It helps you represent your unique perspective and also scaffold a skillset that you’ll need in any class or any career that you’ll have beyond UT,” Bsumek says.

ClioVis’s design tools help students to not only conceptualize narratives, but learn how to structure their own.

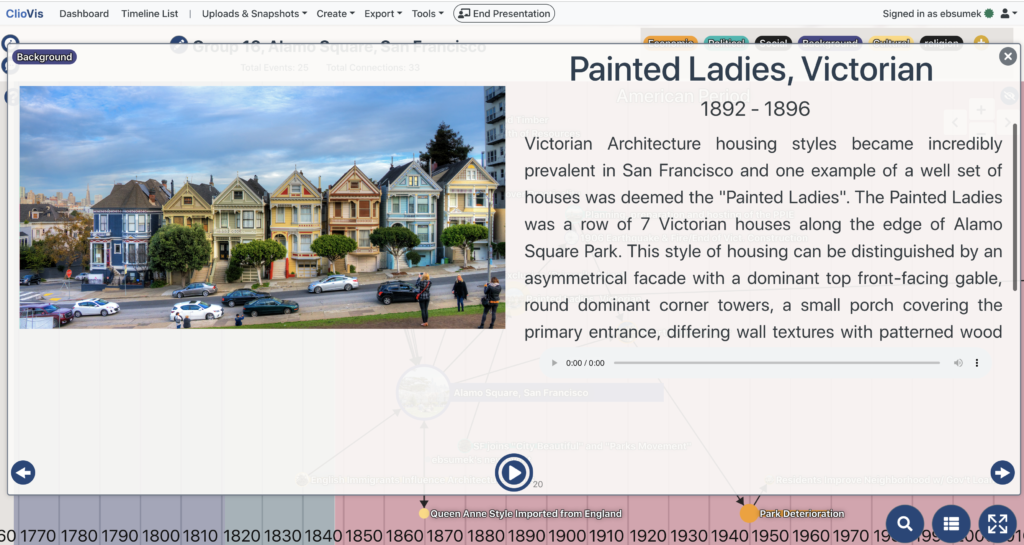

Currently in use in 27 different universities, ClioVis’s success has a lot to do with its dynamic interface. When students create a node, they can add not only a written description of the event, but an image and an audio clip. This allows ClioVis to be used for a variety of final products: as a presentation tool, on autoplay for a “mini-documentary,” or even as a paper after exporting the project’s written components.

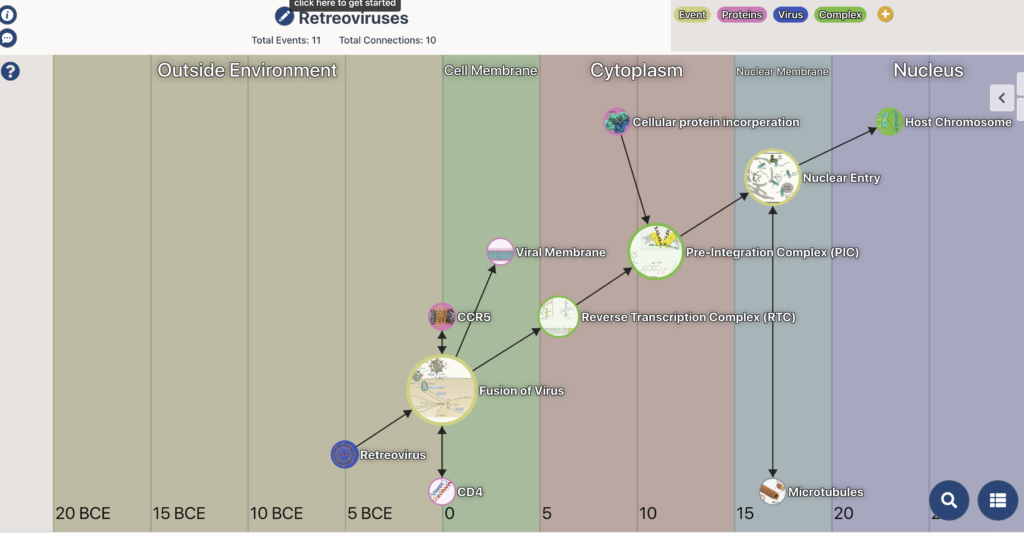

And while created with historical timelines in mind, the platform allows users to edit the x-axis so that the baseline isn’t time. That has allowed ClioVis to be implemented in a wide variety of courses and disciplines at UT that aren’t chronologically oriented.

“It’s been used in nursing, social work, and all sorts of different classes,” Bsumek says. Projects created in ClioVis have explained the chemical reactions involved in glycolysis, displayed engineering processes, and investigated UT’s sustainability practices.

By incorporating multimedia like video and audio clips, ClioVis users can create a variety of products.

ClioVis has been a continual learning process, as Bsumek and a team of undergraduate interns and program developers seek to create an intuitive and accessible platform. The simplified view tool, for example, came from the need to make the platform ADA accessible and compatible for use with a screen reader.

Other design elements, like the audio and video components, have adapted organically, too, responding to the needs of new projects that were being created. “What if you’re doing a history of popular music and you want to add either audio or video recordings of that music?” says Bsumek. “To show how folk or blues gave birth to Jazz, which influenced the emergence of rock and roll, and so on, it would be useful if you could add a recording of a blues artist.”

The next big tasks for the ClioVis team include updating the design, including making font and color schemes more customizable, and improving presentation mode. “It’s just a matter of finding the time and money and learning what people really want from the platform,” says Bsumek. “We take lots of user feedback every year to find out what instructors and students want and need.

After all, the ClioVis team is taking lessons from the platform’s own pedagogical philosophy –– learn from and through the process. “It’s learning by doing,” says Bsumek. “I give students the wider context of social, cultural, and historical factors, then say, ‘Now you go out –– you do additional research, place things in context, and, along the way, try to figure what the connections are.’ Making those connections leads to really learning the material in a fun and interactive way.”

For more about ClioVis or to get started on a project of your own, visit https://cliovis.com/.