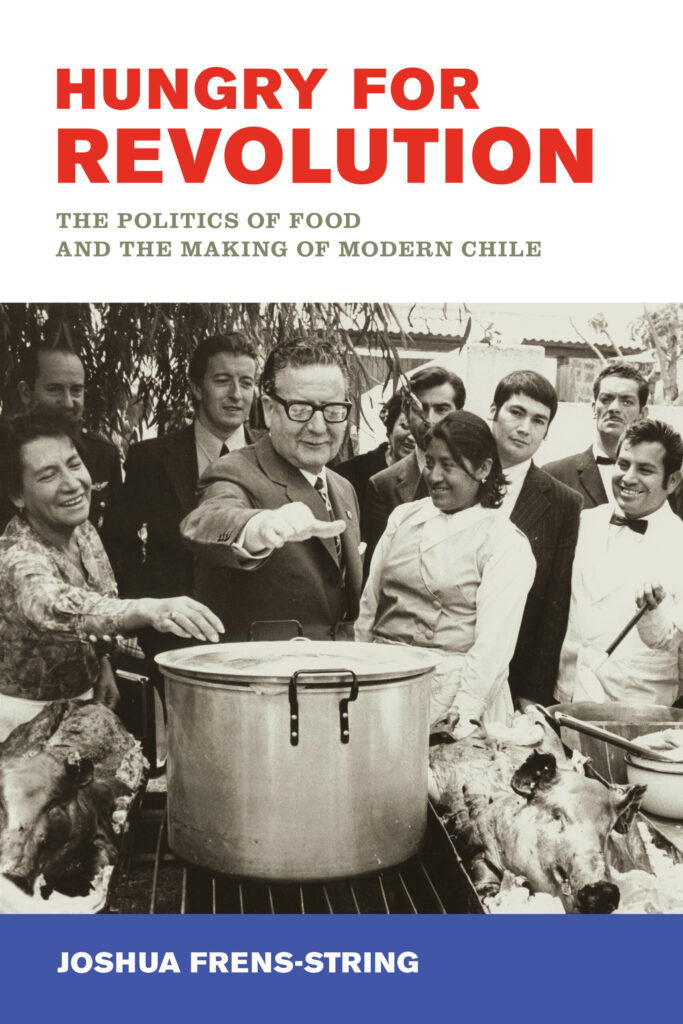

Joshua Frens-String is a historian of modern Latin America and assistant professor in the Department of History. His research and teaching examine the history of revolution in modern Latin America, popular politics, labor history, global agricultural history, food politics, and U.S.–Latin America relations. He is the author of Hungry for Revolution: The Politics of Food and the Making of Modern Chile (University of California Press, 2021), which explores the role of food politics and policy during Chile’s Popular Unity (UP) government. This issue of Portal went to press on the eve of the 50th anniversary of the violent coup that overthrew Salvador Allende, Chile’s democratically elected president, on September 11, 1973, and ushered in almost 17 years of dictatorship by Augusto Pinochet. In this conversation with editor Susanna Sharpe, Frens-String discusses his research and explains some of the factors that weakened Popular Unity’s promising revolution.

As a historian, you frame your work using the lens of food and food politics. How did you first discover that this approach was meaningful for you?

Over a decade ago, when I began research for what first became my PhD dissertation and later my book, I started investigating two political eras that fascinated me as a historian of Chilean labor and the organized political left. The first era was that of the late 1930s and early 1940s, when Chileans elected the first “popular front” government in the hemisphere—a reform-minded coalition that spanned the ideological spectrum from the center to the socialist and communist left. The second era was Chile’s 1000-day experiment in democratic socialism under President Salvador Allende (1970–1973).

As I started looking at archival documents from these two eras, I realized that struggles around food and nutrition tied them together in really interesting ways. To give one example, a milk distribution program, which was a signature achievement of the Allende presidency, could be traced back to the establishment of public “milk bars” and popular restaurants, which took hold in Chilean cities when Allende was the Popular Front’s Minister of Health. The same can be said of mid-century agrarian modernization projects, which relied on different strategies to meet similar goals—namely, more efficient domestic food production and the creation of larger consumer markets for home-grown foodstuffs.

In essence, food became a way to tell the history of these two different periods as a single story, and, moreover, to do so in a way that connected what was happening in the countryside (where food was produced) with what was occurring in the urban areas (where food demand was growing). This is something very few histories of twentieth-century Chile have tried to do.

In your book Hungry for Revolution, you explain how struggles over food fueled the rise of Salvador Allende’s Popular Unity government in Chile. Yet the issue of food ultimately became a point of vulnerability for the regime. Through the lens of food, could you talk about the promise and successes of Allende’s government as well as the factors that ultimately undermined it?

That’s exactly right. Food is a fascinating lens through which to understand the origins of the UP’s 1970 election, as well as the social and economic policies it pursued. At the same time, it helps us understand some of the economic shortcomings of the UP—and perhaps even more significantly, the character and strategies that the opposition used to topple the revolution.

But more than being an interesting window into this turbulent period in Chilean history, food also provides new tools for understanding historical causation—that is, “why” things happened the way they did. For instance, the fact that Chileans had for several decades organized against inflation and food scarcity helps us understand why Allende felt it was necessary to get active, popular support from working people in the price control system he devised to keep these problems in check. (He did this by establishing a vast network of community-run price boards with local consumers.) The long-standing nature of these problems, including economic dependence on expensive food imports, also explains why domestic agrarian reform was so important to the UP government.

At the same time, this long history of food-based struggles helps explain the effectiveness of the opposition. When women opposed the UP government by banging empty pots and pans on the streets of Santiago starting in 1971, their message resonated with many consumers who feared that UP policies were causing old problems like scarcity to return to Chile. Similarly, when U.S. government officials infamously talked about “making the Chilean economy scream” (a line attributed to Richard Nixon by his CIA director, Richard Helms), we can better understand that a major point of economic vulnerability lay in Chile’s dependence on foreign assistance and foreign credit to import food. Suddenly, what the Allende government called the “invisible blockade”—essentially, the U.S. strategy of depriving Chile of outside financial credit and aid—makes a lot of strategic sense, if you’re the U.S. and do not want Allende to succeed. The same can be said of something called the October Boss’s Strike, a month-long antigovernment capital strike in October 1972 that was spearheaded by the truck drivers who made the logistics of Chile’s food economy work.

Looking at Chile’s current political landscape, where do you see the legacies of Allende, of Pinochet, of the last 30-plus years?

When talking about the legacies of the Pinochet dictatorship, we have to begin with the issue of inequality. Because of the economic model that the dictatorship imposed, Chile is today one of the most unequal countries in the world. Over the last two or three years, the fight to rewrite Chile’s 1980 constitution—a controversial document that many see as putting the “rights” of the market and private property ahead of the general welfare of everyday Chileans—has been interpreted by many as a struggle to make Chile more equitable. The Allende era remains so valuable because it represented an alternative, a time when values like social inclusion and equality took precedence over private economic rights or the market.

It’s important to note, I think, that combatting inequality in this way required Chile to first reckon with the human rights atrocities of the Pinochet dictatorship—a process that began in the late 1990s and early 2000s. By making human rights crimes public, and in some cases prosecuting those responsible and repairing the damages of those atrocities, Chileans could then begin to tackle these deep social and economic legacies of the Pinochet years. It is still to be determined if a renewed commitment to social and economic rights among certain sectors of Chilean society will be enough to move away from the Pinochet-era model of what some political scientists have called “protected democracy.”

The struggles of Indigenous Chileans for land rights and autonomy intersect with food and labor politics. What are some of the ways in which that has played out in the last 50 years?

Others have written about this in more detail than I do in my book, but I agree that there are interesting points of intersection between Indigenous land struggles and food and labor history. To put it simply, the Chilean state’s focus on feeding the nation with its own resources in the mid-twentieth century did not usually make room for Indigenous subjects. In fact, with few exceptions, it did not allow much space for rural Chileans of any kind, except in their role as food producers. This was a weakness of the Chilean developmental welfare state. Although many Indigenous peoples’ distrust of the state did not originate with these policies and limitations, I think they did exacerbate their skepticism, and they help explain why issues like autonomy and alternative forms of small-scale agriculture continue to resonate today with many Indigenous communities, particularly in the south of Chile.

Elsewhere in this issue, Tinker Visiting Professor Daniel Party discusses his project “Víctor Jara, Beyond the Martyr.” In what ways does Allende’s death and martyrdom prevent students of history from looking critically at his regime?

There’s a long scholarly and political debate in Chile about the “myth” of Allende and UP. Did Allende represent a firm commitment to political unity and coalition building or radical social change? Was his government “defeated” by foreign and domestic opponents or did it “fail” because of its own political and economic choices? Amid commemorations of the 1973 military coup, these sorts of questions are resurfacing. Allende was a complicated political figure to be sure. His policies not only offended his opponents on the political right but also elements of the more revolutionary left, who wanted social change to occur more rapidly (and often outside existing legal channels). Ultimately, though, as historians continue to study this difficult period in Chilean history, I think we should be careful not to focus on Allende the individual at the expense of understanding the broader social and geopolitical context that conditioned his government’s actions. Under assault internally and externally from the moment he was elected, Allende tried to navigate the increasingly narrow waters of the Cold War, all the while remaining committed to ideals of social and economic justice, democracy, and the rule of law. That’s a really important fact to hold on to.

You teach an Undergraduate Studies Signature Course called Hungry for History. What topics and regions does that cover?

This is a class I taught for the first time in fall 2022. Although not directly related to Chile, the motivation behind the course was similar to the organizing principle of my book, described earlier: this idea that food can be a useful lens to understand complicated social and political concepts but also a powerful way to think anew about historical causation—that is, “why” certain events happen in the way that they do. For example, in the class we talk about how you can’t explain European colonization of the Americas without understanding changing dietary habits and needs back in Europe. At the same time, we talk about how the “successes” of industrialization, whether in the U.S., Europe, or elsewhere, look different when we start considering who is able to consume what types of food and who is excluded from these new consumer patterns.

What can you reveal about your current book project?

One way I got interested in food as a theme for rethinking modern Chilean history was through Chile’s own role helping to feed the late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century world. Few people know that Chile was a major supplier of wheat to the North American West Coast during the California Gold Rush. More important than that, Chile was an important source of nitrogen-rich agricultural fertilizers at the turn of the century, by way of the world’s largest naturally occurring stores of sodium nitrate in the Atacama Desert. The Chilean nitrate economy was thus vital to the early development of industrial, input-intensive agriculture in Europe and later the United States.

My current research digs deeper into the role that Chile played in shaping global agriculture—and by extension the global environment—through its production of mineral nitrogen in the early-mid twentieth century. While the Atacama Desert is today the hope of “green” industry because of its lithium deposits, there’s an important story to tell about how, in an earlier period, this same region fueled a “green” revolution in agriculture.

This story was originally published in Portal, the magazine of LLILAS Benson Latin American Studies and Collections.