Call it a singular job perk: When Seth Garfield’s friends and family spot a can or bottle of guaraná soda on their travels, they snap a photo to send him.

It makes sense that they’d think of Garfield when they see the soft drink, which is best known as the “national soda” of Brazil but is available throughout South America and, to a lesser degree, in other parts of the world. In his newest book, Guaraná: How Brazil Embraced the World’s Most Caffeine-Rich Plant (University of North Carolina Press), Garfield, a professor of history at The University of Texas at Austin, explores the history and cultural significance of the soda’s namesake plant, which is native to the Amazon basin.

More than that, though, Garfield uses the plant as an entry point to an engaging history of Brazil, weaving together the stories of the Indigenous Sateré-Mawé people, who first cultivated it, and the many others whose paths have intersected with guaraná over the centuries. Together, those stories reflect how “colonialism, capitalist expansion, Western science, and nationalism have shaped Brazilian society over time,” he writes.

The soft drink, which contains a trace extract of the plant, is the most widely known guaraná product. In Brazil alone, Garfield reports, people drink more than 17 million bottles of it a day. (While some describe the taste as akin to cream soda, Garfield likens guaraná soda to a very sweet, caffeinated ginger ale.)

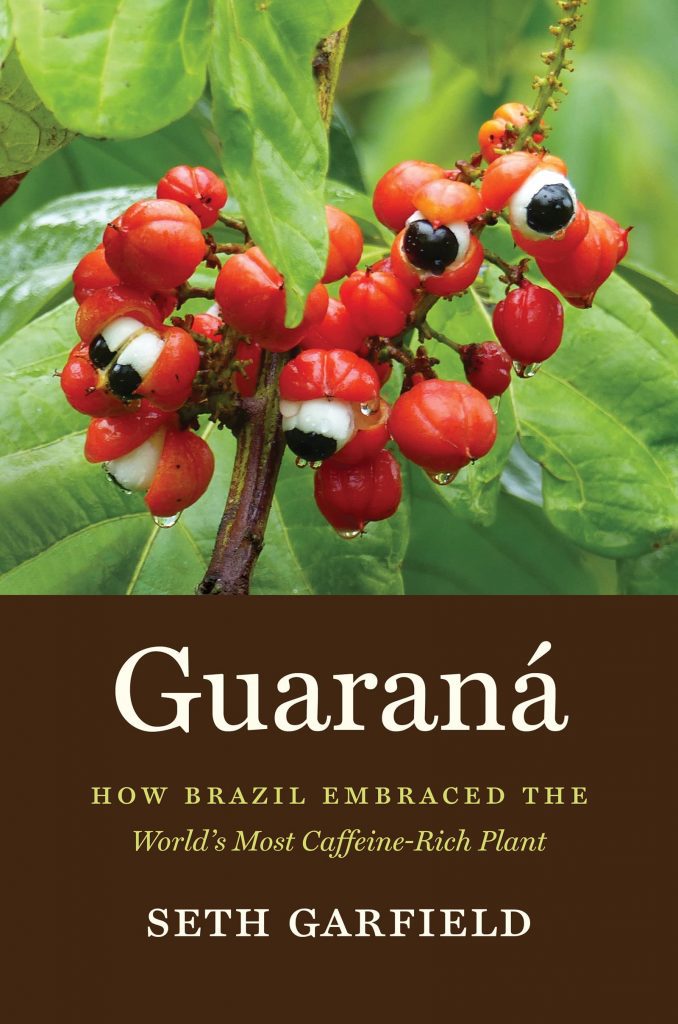

As he explores in his book, though, the plant’s significance to Brazilians is much broader. Guaraná plays a key role, for instance, in a traditional origin story of the Sateré-Mawé of the Lower Amazon, whose roughly 13,000 members make them one of the largest Indigenous groups in Brazil. According to the legend, a young boy with the power to heal and bring peace was murdered by a jealous uncle. At the direction of a god, the elders of his village planted his eyes. From that spot, a guaraná plant bloomed, watered by the tears of the community. The distinctive appearance of the plant, whose fruit’s dark seed resembles a human eyeball, represents the child’s resurrection.

The Sateré-Mawé, who call themselves “the children of guaraná,” valued the caffeine-rich plant for both medicinal and spiritual purposes. “In their myths of origins and their histories and cosmologies, they talk about guaraná being the origin of wisdom, of all knowledge,” Garfield says. Rituals for consuming a beverage made from the plant’s seeds were incorporated into community ceremonies.

Eventually, outsiders came to see the value of guaraná — namely, its high caffeine content and the voracious consumer demand for it. From local traders to colonizers, U.S. pharmaceutical companies to Brazilian soda marketers, these outsiders repurposed the plant for their own commercial purposes. During the 19th century it was widely used in patent medicines, “strengthening” tonics, and treatments for conditions ranging from headaches and “nervous exhaustion” to dysentery and gonorrhea. Guaraná’s cachet as a therapeutic eventually began to wane, due to its high cost and the emergence of cheaper synthetic drugs such as aspirin. But its popularity as a soft drink ingredient took off in Brazil, buoyed in large part by rising urbanization, the entry of middle-class women into the work force, the proliferation of commercial leisure, and the burgeoning advertising industry, which pitched the caffeinated product and its Amazonian origins as a source of energy and “vigor.”

“Amid the expansion of domestic industry, middle-class consumption, and mass media giving rise to ’modern’ Brazil, guaraná soft drinks bobbed as symbols of self-fulfillment and social progress,” Garfield writes.

The beverage has become an enduring source of national pride. When Ingrid Bergman and Cary Grant came to Brazil in the mid-’40s to film Notorious, for example, newspapers boasted of the stars trying the soda. “This is actually a trope in Brazilian popular culture, this nationalist rhetoric about how wonderful guaraná soda is and how foreigners especially should be very impressed with it,” says Garfield. The marketing of the “authenticity” of guaraná sodas served as well to discredit a key commercial rival, Coca-Cola. While the soda remains the most popular guaraná product, the plant is now used globally in a wide array of products, from health supplements to energy drinks to cosmetics.

Garfield’s book not only traces the history and social significance of the guaraná plant but also provides readers insight into the methodologies of a historian. Not much had been written about the topic before, leaving Garfield to cobble together diverse sources — accounts by missionaries, scientific articles, Sateré-Mawé narratives, vintage advertising, corporate documents, and travel writings — each of which offered a distinct angle on Brazilian history. “I wanted that multidimensionality to be one of the main takeaways from the book,” he says. “I didn’t want people to walk away with this narrow history of a plant, of a soda. I wanted people to be able to use guaraná as a window into all those facets of Brazilian history, to see that Brazilian history is fascinating, it’s complicated, it’s dynamic. And the plant, because of its many different journeys and incarnations, would allow me to do that.”

He also wanted to draw attention to the largely overlooked role of the Sateré-Mawé in the story of guaraná. “They are citizens of Brazil but also a marginalized minority group,” he notes, and “throughout their centuries-long history of interethnic contact, they have striven for selective inclusion while at the same time upholding their cultural distinctiveness as an ethnic group.” The group’s current commercialization of traditionally sourced guaraná through alternative food networks is the latest version of this historical pattern.

Garfield hopes that his sweeping account will open up readers’ minds to the complexity of Brazilian history and dispel stereotypes about the nation and its people. “That’s what history and the liberal arts do best: they uncover and illuminate what it means to be human in different cultures and in different moments in time,” he says.