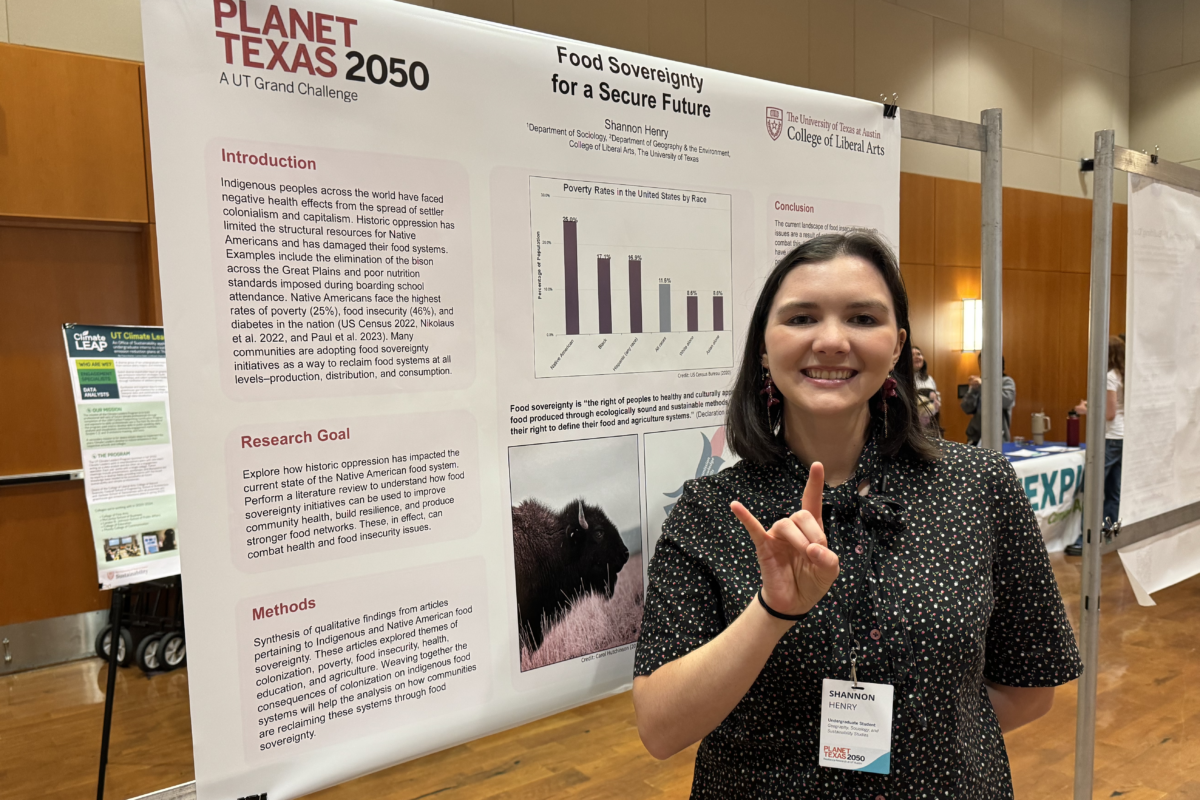

Third-year COLA student Shannon Henry has never been a fan of public speaking. Yet, in late February, she found herself presenting a poster at Planet Texas 2050, an annual symposium created by interdisciplinary research teams at UT.

“Going into the presentation, I was talking to a professor and he asked, ‘How are you feeling about it?’ I was like, ‘You know, I’d be happy if no one came to see it.’ I was really scared,” Henry remembers. But she overcame her nerves to give a successful presentation and found it was a positive learning experience. “I hope I can do it again next year,” she said.

Planet Texas 2050 is a UT “Grand Challenge” initiative co-founded in 2018 by an interdisciplinary team of faculty from across the university, including English professor Heather Houser, and is dedicated to finding ways to make Texas more resilient in the face of climate change and increased resource demands. This year’s symposium featured several panels of experts discussing pressing issues such as extreme heat in Texas, air quality and pollution, and disaster preparedness. Faculty and student researchers from a variety of colleges and disciplines participated, including COLA doctoral student Elybeth Alcantar and Laurel Mei-Singh, an assistant professor of geography and Asian American studies, who spoke in a lightning talk cluster about community-based research and scholar activism. Henry participated in the research poster session.

As a triple COLA major in geography, sociology, and sustainability studies, the event was a natural fit for Henry’s studies and interests, even with her presentation nerves. In fact, her poster, “Food Sovereignty for a Secure Future,” began as a paper for a COLA class.

“The content for the poster came from a sociology class I took last semester called ‘Food and Society’ with Kelly Fulton. We had to write a literature review and I chose to do mine on Native American food systems and food sovereignty,” Henry said. “A lot of this project came from me not knowing. I wanted to learn, and then I learned, and I was like, ‘Okay, I feel like a lot of other people should know about this.’”

Her presentation addressed the food systems of Indigenous peoples in the U.S. and Canada, which have been damaged by historic oppression. Henry said she wanted to amplify the voices of Indigenous and Native American communities and people fighting for a better food system through food sovereignty, which she described as “giving people the power to define and manage how their food is produced, distributed, and consumed.”

“I think most people know about colonization and capitalism and the negative effects it had on Indigenous peoples, but one way Indigenous communities were harmed was through food,” she explained. “Food sovereignty came about to give people more control over their food systems, the production, consumption and distribution.”

In preparing her research paper and poster, Henry found that the population of bison in the North American Great Plains dropped from 30-60 million to just 300 as the U.S. government encouraged bison hunting to force Native Americans to relocate to reservations. Many Indigenous and Native American children were later required to attend boarding schools in the 19th and 20th centuries as part of an effort to force assimilation into white society. While these schools and the abuses they inflicted on students are known, the impact on children’s nutrition is often overlooked. Native American children frequently went hungry at these schools, Henry says, and when they were fed, the food was often in poor condition.

Though these events took place many years ago, the consequences remain. Henry found that one of the leading causes of death for Native Americans is diabetes, and a weighted average of 46% of Native people in the U.S. — about 3.1 million people — are food insecure. They also are more likely to live in rural areas, which are often food deserts.

Henry said she believes the food sovereignty initiatives that Native American and Indigenous communities are adopting could provide a solution to these problems and help repair their food systems. These initiatives include building community gardens to grow native crops and efforts to reintroduce traditional foods such as bison, salmon and camas, a plant in the asparagus family. These initiatives not only restore the environment but can also allow people to connect with their culture.

“Food is one of the few things that everyone has in common,” Henry said. “If we can find ways to make it more equitable and sustainable, it’ll be better for everyone.”

Despite her initial apprehension, Henry said she was glad she presented her work at the Planet Texas 2050 symposium and that she had some great conversations with attendees.

“There was someone I met at the last minute who works in France for a company working with AI, and she really liked my poster and talked about how it connected to her work,” Henry said. “Then someone who works at a food forest in Austin scanned the QR code on my poster that linked to the paper I wrote. She was like, ‘I really hope that we can use some of these things in your conclusion and try reintroducing traditional foods into the food forest. That would be a really cool initiative.’”

Henry also has a message for her fellow COLA students who may be interested in participating in something like Planet Texas 2050 in the future.

“If you’re nervous for it, just do it,” she said. “My event was all students from the College of Natural Sciences. COLA research is more theoretical, but I think it’s important to share that with others. COLA is important, the liberal arts are important.”