As a child in Soviet Ukraine, Oksana Lutsyshyna started writing fiction to escape what she describes as the “somewhat grim and very uninteresting” reality of life behind the Iron Curtain. But she didn’t start where you might expect, with fairy tales or simple wish fulfillment fantasies. Instead, Lutsyshyna wrote detective stories.

“They were horrible!” she says when asked about these first pieces. “I was 12 and I had no idea how a detective story should work apart from reading Agatha Christie. It was something about people being killed and somebody investigating it, and then at some point I ran out of things for them to do.”

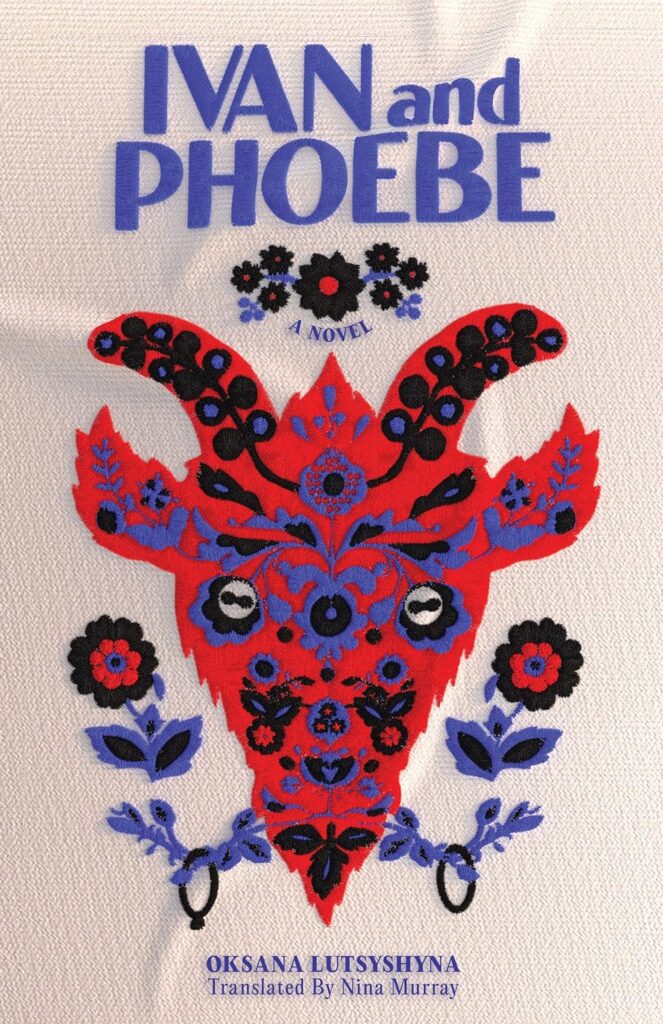

Now an award-winning novelist and poet — and assistant professor of instruction in UT Austin’s Department of Slavic and Eurasian Studies — Lutsyshyna has long since left detective fiction behind. Still, something of the genre lives on in her latest novel, Ivan and Phoebe, a book of silences, disappearances, and psychological strain.

The novel, Lutsyshyna’s third, follows the titular couple through Ukraine’s final years under Soviet control and into the first of its independence. At the story’s heart is Ivan’s participation in what became known as the Revolution on Granite, a 16-day student protest and hunger strike that occupied what is now Kyiv’s Revolution Square, or Maidan Nezalezhnosti, in October 1990. Also known as the First Maidan, the Revolution was the first major political protest to occupy the square, though others would later follow.

“There are many reasons to believe that this revolution was the matrix for the other two Maidans that came,” Lutsyshyna says. “It was the first time that Kyiv saw that you can be a political activist and you don’t have to do anything violent.”

But just because the Revolution on Granite is a foundational moment in the history of Ukrainian protest and activism doesn’t mean it’s common knowledge, even in Ukraine. Without internet, text messaging, or social media, coverage of the revolution was limited to traditional, “slow” media, which was further limited by Soviet censors and propaganda.

“Even people who lived in other parts of Ukraine had no idea that this was going on because the newspapers were not writing about it,” Lutsyshyna says. “When my parents read this novel, my mother was like, ‘Oh, I didn’t realize there was this whole revolution.’ So even now, people are still catching up to the events.”

First published in Ukraine in 2019, Ivan and Phoebe quickly won two of the country’s most prestigious literary awards, the Lviv City of Literature UNESCO Prize and the Taras Shevchenko National Prize in fiction. Last year an English translation by Nina Murray was published by Dallas’ Deep Vellum Press, making Ivan and Phoebe broadly available to American readers just as the ongoing Russo-Ukrainian war sharply escalated and news from Kyiv and the Donbas was splashed across American media. Reviews of the translated novel have often pitched it as an entry point for readers in the U.S. curious to learn more about Ukraine, but Ivan and Phoebe also functions as an introduction for Ukrainian readers interested in an often-overlooked period of their own history.

Lutsyshyna was drawn to the Revolution as the subject for a novel by her own desire to understand what happened that October in Kyiv, when she was 15 years old. She read all she could find on those 16 days — old Soviet newspapers, conference proceedings, and timelines — and interviewed participants about their time on the granite. She also researched the history of the Ukrainian dissident movement and was struck by the complexity of their fight for their country.

“They had to protest against that totalitarianism and also against Russian imperialism and colonialism, and they had to come to the awareness of that colonialism,” Lutsyshyna says. “Try doing that if you don’t have any basic texts, if your history is buried, if people who know and think that are either killed or silenced or sent to prison.”

The fight over Ukraine’s history is very much alive — Russia has used its own, highly contested version to justify its ongoing efforts to annex large swathes of the country — and the struggle to learn and integrate suppressed Ukrainian history is a theme woven throughout Ivan and Phoebe. Ivan, a student from Uzhhorod (Lutsyshyna’s own hometown), moves to Lviv for university. There he joins the revolutionary movement after having a kind of conversion experience while looking at paintings of figures from Ukraine’s past, and the memory of those who have fought before him continues to give him strength throughout the protest and beyond.

Ivan’s understanding of the past and its reach into the present isn’t naïve, exactly — he and his compatriots know enough recent history to expect that their protest will end in police beatings, prison sentences, or both. But the students share an almost romantic optimism about what a free Ukraine will look like. Reality can’t keep up, and in the months and years that follow — years that see Ukraine emerge from the U.S.S.R. in 1991 as a fragile, fledgling democratic state — several of Ivan’s fellow protesters are killed or driven out of the country.

Ivan himself, who is terrorized for months by a former KGB officer with unknown motives, struggles to keep sane amidst his growing paranoia. At the same time, Ukrainian society at large struggles to adjust to democracy and capitalism. The power flickers on and off, banks crash, oligarchs emerge. Life becomes confused. As one stranger shouts at Ivan, “Tell me, what’s this independence we got going on now? How am I supposed to live?”

After fleeing back to Uzhhorod, Ivan soon marries the poet Phoebe in a bow to convention and family pressure. The story of the relationship that follows is one of slow-moving disaster. Ivan, feeling incapable of connection or communication after what he sees as his failures in Lviv, lashes out at Phoebe and destroys the only copy of her poems. The young couple live with Ivan’s domineering mother, Margita, and his father, who has long since abandoned himself to drink. Margita persecutes Phoebe; Ivan does nothing to intervene; and Phoebe becomes little more than a haunting shadow in the house, the specter of women’s lives crushed by patriarchy and convention. We hear her voice directly only twice, in monologues that narrate a life of abuse, assault, and abandonment.

Phoebe’s story, just as much as Ivan’s, is a narrative of history and the need for change. Both find themselves trapped in a suffocating society, frozen by expectations and tradition, and both must work towards a second kind of revolution — personal, domestic, and artistic. By the novel’s close both Ivan and Phoebe have begun to pick their own ways to a new kind of freedom. Nothing’s certain and everything’s in flux, but there’s a fragile hope burning at the end.

That movement from hope, through bruising disappointment and the backwards pull of convention, and finally towards hope again could describe not only Ivan and Phoebe but the struggle for independence writ large. This isn’t a coincidence; in both her creative and academic work, Lutsyshyna is interested in postcolonial and decolonial questions, which run through works like Ivan and Phoebe and her 2019 poetry collection Persephone Blues as well as her scholarship on postcolonial Ukrainian writers such as Oksana Zabushko.

Alongside her creative and her academic work, which also explores Polish and Ukrainian modernisms, Lutsyshyna is a prized member of UT Austin’s teaching faculty, leading courses on subjects from the Chernobyl disaster to “Satire and the Political Novel in Eastern Europe.” Whatever the course title, Lutsyshyna prioritizes conversation and insists she learns alongside her students. And, of course, her teaching feeds back into her thinking and writing — about Ukraine, about history, and about the possibilities for storytelling.

“Everything, or almost everything, reveals itself to be a narrative,” she says. “And I learn a lot from leading my seminars, too. As I always tell my students, the main acquisition in life for any thinking person is to have a good interlocutor — preferably, several good interlocutors. That’s how we create and that’s how our thought develops, in dialogue.”

But while dialogue develops thought, writing is a fundamentally solo art — and Lutsyshyna isn’t yet ready to share details about what she’s working on next.

“Actually, we in Ukraine are superstitious this way,” she says. “We think it is best not to tell anyone about such things, so as not to jinx the process.”

To listen to an extended conversation with Lutsyshyna about Ivan and Phoebe, the legacy of the Revolution on Granite, and her work as a poet and scholar, visit our Extra Credit Substack newsletter and podcast.