The liberal arts at UT Austin are thriving, which may come as a bit of a surprise. Nationally, fewer undergraduates are majoring in humanities programs. Some universities are prominently cutting funding for the liberal arts and in some cases whole departments. When other university administrations tell the “brand” story of their institutions, they often emphasize advances in science, technology, and health.

Last year The New Yorker ran an incredibly depressing article on “The End of the English Major” that emphasized that even literature-loving Harvard students, earning the single most marketable university pedigree in the world, don’t feel free to follow their intellectual bliss. Instead, they major in something they perceive as more practical and take a few courses in the English department on the side. As a result, the trends are bleak: “From fifteen years ago to the start of the pandemic, the number of Harvard English majors reportedly declined by about three-quarters — in 2020, there were fewer than sixty at a college of more than seven thousand — and philosophy and foreign literatures also sustained losses.”

For a variety of reasons, the picture isn’t at all bleak at UT. There have been declines in some of the traditionally larger humanities majors, but they’ve been modest by comparison to what a lot of schools have seen. Growth in interdisciplinary majors that incorporate humanities fields and social sciences have more than offset those declines. In general, we’re doing well, but the challenge for a salesman like me remains roughly the same. How do you sell the liberal arts in a world where the liberal arts are frequently portrayed as on the decline and on the defensive?

One way I sometimes think about it is that there two narratives we typically have to offer. One is that the liberal arts are in fact modern and pragmatic. We’re good at teaching highly marketable skills like writing and good at cultivating important soft skills like leadership and collaboration. Our graduates go on to get good jobs. We have a great career services office. And so on. You don’t need to be worried about getting a job after graduation. We’ve got you covered.

The other approach is to emphasize the more old-school virtues of a liberal arts education. Students get to read the best and most beautiful things that have ever been written. They get to spend time delving into the big questions: Why are we here? How should we live? Why is society shaped the way it is? Where does power lie, and why? If you want college to be a transformative intellectual experience, there’s no better place to study than a college of liberal arts.

In practice we put forth both of these narratives, often at the same time. We tailor our message to different contexts and audiences. That’s the job, and I am not beset by deep angst every time I draft an email to one of our constituencies, or make an assignment for the magazine, that emphasizes one of these narratives at the expense of the other. I’m responsible for communications for this specific place with its specific needs, not “the liberal arts” as a broader institution in our culture. I don’t need to make a big philosophical decision about Who We Are, and it would be irresponsible of me to subordinate the needs of the college to some grand unified vision of how the liberal arts should be marketed.

If I were emperor of communications for the liberal arts in America, however, and had both the responsibility to tell the larger story and the power to enforce a coherent message across all the individual entities that constitute “the liberal arts in America,” I would make us settle on one big narrative. The alternative is a muddiness and defensiveness in messaging that in the long run can’t help us reclaim territory from the scientific, technological, and moneymaking disciplines. To reclaim territory, we’d need to go on the offensive.

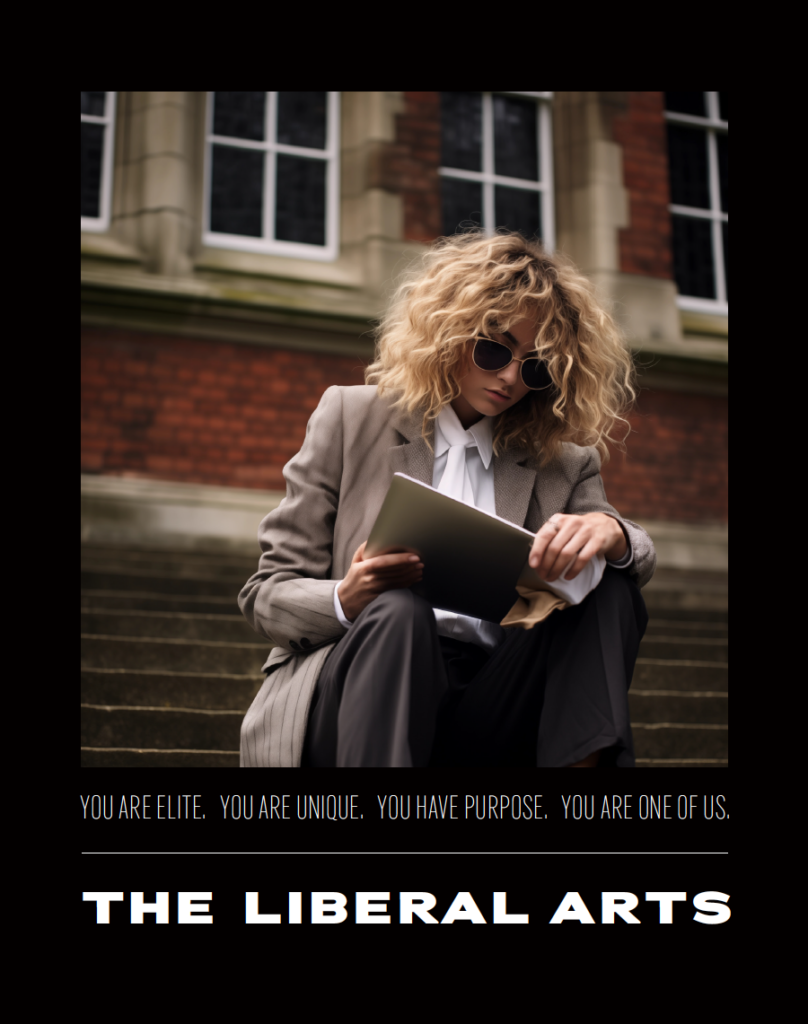

The big narrative I’d choose, however, wouldn’t be either of the two I mentioned above, though it would have elements of each. Instead, it would be a story that sells the liberal arts in the same way that most things in America are sold, by appealing to our desires. In particular, I’d want to craft a campaign that positioned a liberal arts education as an experience that can satiate three particular desires: our desire for status, our desire for distinctiveness, and our desire for meaning. You want a liberal arts education, it would convey, because you are elite, you are unique, and you have purpose. And you are these things, in particular, relative to the other kinds of degrees you can earn at a place like UT, the “practical” ones (with “practical” said with some condescension) which are all well and good for people who are interested only in following the herd, getting an office job, grinding it out, checking the boxes. For those people, it makes sense to get a job in the technical or money-making fields. For you, though, remarkable and purpose-driven creature that you are, the only possible degree is one that challenges you to delve into the mysteries of the world, understand yourself and society better, and cultivate the virtues that distinguish the best among us now as they did in ancient times. For a rare and precious gem like you, the only possible degree is a liberal arts degree.

For this hypothetical campaign, I imagine a visual aesthetic that’s in the vicinity of what the fashion designer Rachel Comey created for her collaboration with The New York Review of Books. High end, bookish yet glamorous, tactile.

I fear I sound cynical here. I’m not. I’m actually painfully earnest, and painfully aware of the decline in the fortunes of the kind of liberal arts education that I loved so much as an undergraduate and graduate student. Our faculty’s job is to teach, research, and write. Our students are here to learn. I’m here to sell, and I happen to be the best kind of salesman, which is someone who believes in the product. I am not, alas, the emperor of liberal arts communications in America, nor is there a reasonable prospect that I will be. A salesman can dream, though, and write the occasional column.