Ward Keeler on Life as an Anthropologist

Ward Keeler is a professor of anthropology at UT Austin whose research focuses on the performing arts, language, gender, and hierarchy in Indonesia and Burma (now Myanmar). He is the author of, among other things, Burmese: A Cultural Approach (Hong Kong University Press) and Traffic in Hierarchy, Masculinity and its Others in Buddhist Burma (University of Hawaii Press). I spoke to Keeler for Extra Credit, our Substack newsletter and podcast. This is a short excerpt from our conversation. Visit Extra Credit to hear the whole podcast conversation.

—

Daniel Oppenheimer: I want to go back to you at the age of 17, when apparently you already knew you wanted to be an anthropologist. I’m thinking back to myself at age 17. I guess I knew in some vague sense that there were such people as anthropologists, but I certainly didn’t have a clear enough sense of the field to imagine that it would be something that I’d want to do. Can you bring me to that place and how 17-year-old you knew that you wanted to be an anthropologist?

Ward Keeler: I have to go further back than that actually, to when I was seven years old. My fourth-grade teacher assigned all of us the task of writing a letter to a person who had the job we wanted to have when we grew up.

I told my mother I had this task and said I wanted a job where I got to travel. And she said, “Oh, well, then you want to be an anthropologist.” She had gone back to school after she had four kids and had taken a course in anthropology at N.Y.U, and she had really enjoyed the course. I wrote to her N.Y.U. professor, Dr. Joseph Brahm, and he wrote me a very nice note back, which I still have in my files.

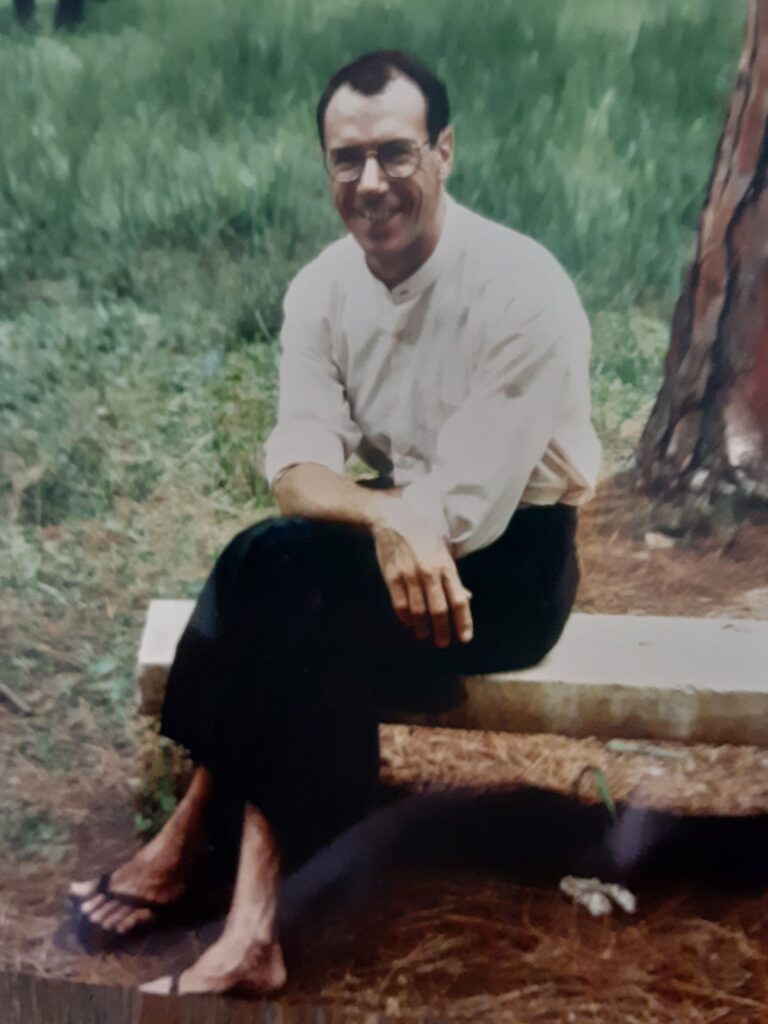

or ’88, photo courtesy of Keeler.

Then when I was 17, I was in a summer program at Cornell, and I said to a French literature professor, “I can’t decide whether I should be a French lit major or an anthropology major.” I said, “Anthropology can’t be as romantic as it sounds.” And he said, “What do you mean? Every cocktail party I go to, the anthropologists always have the best stories.” And I decided as I walked home that, yeah, I’m an anthropologist. And it was great because it meant that from day one in college, I knew what I wanted to make the focus of my work.

I also knew, because I’d seen The King and I as a kid, that Southeast Asia fascinated me. And Cornell has one of the best Southeast Asia programs in the country. So I started studying Indonesian the first morning of my first semester at Cornell. And that was great because it meant I was in a coterie of people, most of them grad students and professors, who were interested in Southeast Asia. It was hugely advantageous.

Oppenheimer: You mentioned that your interest in Southeast Asia was sparked by The King and I. Can you tell me more about that?

Keeler: It’s a little bit shameful for an anthropologist to admit that that’s where his interest was originally sparked. It’s very politically incorrect. The film, which is about the tutor to King Mongkut’s children in the 19th century, is considered deeply insulting to the Thai monarchy.

Oppenheimer: It’s interesting you frame it that way, as politically incorrect, because one of the things I wanted to talk to you about was the extreme — I guess the nice way to put it would be the extreme introspection of the anthropological profession, or maybe its extreme self-laceration.

In your article “Incitement to Fieldwork” you write about the important reflection that your discipline has done on the ways you’ve exoticized others or brought your own biases or preconceptions to the study of people from other parts of the world. Then you go on to say that maybe you also need to bring to your work an introspection that’s more individual, more about your own neuroses and psychological particularities rather than cultural or social biases.

It made me think about whether those two kinds of introspection could be in tension. I’m sure that as a discipline anthropology does have exoticization and Orientalization to atone for, but it also seems to me quite neurotic the degree to which you experience discomfort around saying something as simple as, “I saw some pop culture about another part of the world, and it seemed exciting and romantic and exotic to me.”

Keeler: Yes. In 1986, there was a famous collection of essays that critiqued anthropology and the ways it had treated, or mistreated, other parts of the world. It aroused such anxiety among anthropologists and particularly among graduate students that there was a terrible failure of nerve. The notion prevailed that we really shouldn’t be speaking for them, whoever those others are. Therefore, we can only really study people who are like us.

I consider that a complete betrayal of the entire rationale for anthropology, which is that we can actually learn something about ourselves by learning about other people. I don’t think that is Orientalist or neo-colonial or whatever else. I understand the feeling, “Who are you to be representing them?” But am I ready to say that a foreigner who comes to the U.S. and describes American society has no more interesting perspective or insight than I have as an American? No, right?

Or I could make the analogy with psychotherapy. I think most Americans would be willing to admit that a therapist might have a different take on our own ideas and thinking and behavior than we do from the inside. And it’s a revelation to be able to at least compare those different perspectives.

I am to this day quite willing to set out an analysis of what I’ve seen. And of course, I expect people to contest it. But every scientist expects to have their ideas contested, the more the merrier.

Oppenheimer: Since the beginning of your academic career, you’ve had a fascination with hierarchy. For a long time, it was about ideas of hierarchy in Southeast Asia, but more recently you’ve been applying that frame to the U.S. as well. Do you have any theories as to why you’ve found hierarchy so fascinating? Is it mostly that if you end up as an American going over to Southeast Asia, it’s just going to hit you in the face that there is such a distinct relationship to hierarchy compared to the U.S. or other Western cultures?

Keeler: As soon as I got to Java, I started learning the Javanese language, which has the most elaborate speech registers of any language in the world. Every time you open your mouth in Javanese, you have to commit yourself to what you consider your status to be relative to the person who’s listening to you. And even about other people you may be talking about. Hierarchy hits you in the face the minute you start studying this.

Oppenheimer: You even have a specific language you use with your father, right, that’s distinct from everyone else in your family?

Keeler: It isn’t every verb by any means, but it’s all the important verbs. To say, to give, to take, to ask, to eat, to sleep—all of those have special honorific forms you use when you speak to or about your father. And if you’re well-bred, when you speak to him you should be using a special of self-humbling vocabulary about yourself as well.