This essay was originally published on Extra Credit, COLA’s Substack newsletter. Learn more about Extra Credit and subscribe here.

My friend and colleague Paul Woodruff passed away in the fall of 2023. Paul was a philosopher and a commanding presence at The University of Texas for over 50 years. He directed and worked in some of the university’s most important units and taught tens of thousands of undergraduates and graduates.

I came to know Paul in his administrative roles and I taught alongside him in a unique graduate program1 designed to extract lessons from the liberal arts and adapt them to organizations. I had the bittersweet pleasure of co-teaching a graduate course on “Leadership” with him in his last semester. He was a master of that subject, among many others, and he taught me some important things that are worth sharing.

Build things

Paul was a man of ideas, many of them baked into poetry, plays, and ancient texts. But he was also someone who built things. Some of these things were institutions. He left behind a complex of organizations at The University of Texas that were handcrafted and tuned by his leadership. One of these is the Undergraduate Studies program, which is devoted to fostering the intellectual life of all undergraduates, whatever their major. It’s a sprawling mission but one that is singularly important in a university built around graduate-level, prize-winning research. Paul built programs that reminded undergraduates of the benefits of being part of cutting-edge ideas. Another is the storied Plan II honors program in liberal arts — not a Woodruff creation, for sure, but certainly one that thrived under his leadership. To this day, Plan II feels to me like a Woodruff program in its intensity and thoughtful, off-beat vibe. Same with Human Dimensions of Organizations (HDO), UT’s elite program in people-centered organizational design — a very different kind of management program. HDO launched just as Paul was looking for his “next thing.” He joined the faculty in the program’s first year, and since then, every HDO cohort has ingested his lessons on leadership, a core and required part of the HDO experience.

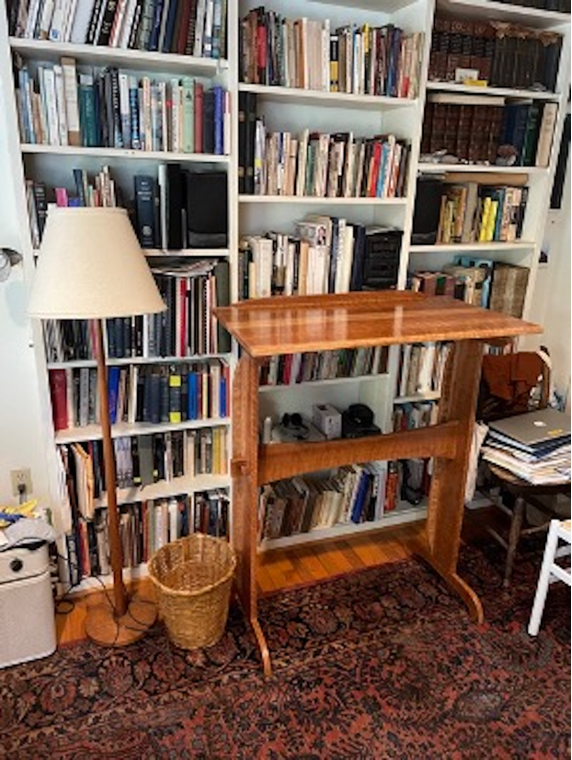

But when I say Paul built things, I mean Paul built things, and mostly out of wood. He designed and crafted furniture that he used every day in his work, such as a beautiful writing table that seems to invite ideation. Another piece is a standing desk on which he conducted his online classes during the pandemic. But his signature pieces were elliptical tables. Paul could talk forever, it seemed, about the functionality and superiority of the ellipse. For Paul, a good dinner or seminar started with an ellipse. He would tell you that one of his large elliptical seminar tables would allow all 20 participants to look each other in the eye. It’s true, and the benefits of that geometry feel real, especially after he reminded you of them. His masterpiece, I think, is the seminar table in the Joynes room in Carothers Hall, the spiritual home of Plan II. In classic Woodruff fashion, the table features elegant, simple, and strong joinery. It’s a monumental table, but not fussy; it can be disassembled and re-assembled fairly easily, as he would be quick to tell you — almost as if he were letting you know that the institution shouldn’t feel obligated to keep it. But, of course, no one would entertain the notion of moving it. It’s beautiful, practical, fits the room perfectly, and — I can attest — hosts vibrant discussions.

Respect the work, respect the people

On campus, it was rare to see Paul without his trademark bow tie. I admit that I can be suspicious of the bow tie, even if I appreciate its quirkiness and fun. But Paul loved the theater and he recognized the power of a costume. That’s not to say the bow tie was any sort of affectation. Paul’s point — and he was adamant about this — was that you had to show respect for the classroom, for the teaching, for the work, and for the students. Dressing the part did that. His bow tie told the students (and maybe himself), “this is important to me and I am here to give it everything I have.” And he did give everything, which is why students loved him, even if they couldn’t always see the point in a Shakespeare play or a story from ancient Greece.

Paul also knew that a new scene required a new costume, and off-campus he was more likely to be in shorts and a t-shirt. He and I (and likely many others) would meet at Texas French Bread (TFB), where he held court. Every time I was there, some ex-philosophy student came out of nowhere to greet him. Teaching philosophy in our Slacker town for 50 years means that the streets are crawling with your disciples. When Texas French Bread tragically burned down in January of 2022, a part of Austin died. I know Paul was affected, but he took it in stride. “They’ll rebuild,” he’d shrug. And so they are, and the place will probably be even better, if different. And when they’re done with the forms, approvals, and years that is City of Austin permitting, I’ll be one of the first in line for a chicken salad sandwich. Murph Willcott, the owner of TFB, was a Woodruff friend and a former student. He’ll keep the Woodruff vibe alive, maybe even with a Woodruff elliptical table. Paul connected with people.

Words matter

Paul prepared the syllabus for the course we taught. Again, it was a course meant to teach mid-career professionals the art of “Leadership” through great works of philosophy and literature. It was decidedly his course — he had invited me to co-teach it, for whatever reason, and I was along for the ride, holding on tight. When I came home with a stack of books for the semester, including several Shakespeare plays, my wife openly guffawed. “You’re teaching Shakespeare? You? Ha!” “Uh…yeah?,” I stammered, “do you have to be that surprised?” But it’s true, I’m a political scientist, with zero business teaching Shakespeare, even if I had operated the lights for a friend’s staging of The Tempest 30 years ago.

Over that semester we read not only Shakespeare, but also Melville, Sophocles, Thucydides, Homer, Machiavelli, and Confucius. A course on leadership, for me, might have featured lessons from social science, with as much verifiable evidence as possible. It was going to be a different kind of semester, maybe a bewildering one. Not only was Paul an authority on these texts, we were reading his translation of the Greek ones. My role was something like the straight man. Actually, I’m not sure I know what my role was, but I loved it.

These books were packed with good stories about both heroic and tragically inept leaders, and there is nothing like a course on ancient texts with someone who has translated the damn things. Each word mattered in ways that you came to appreciate deeply. And Paul’s translations were utterly modern, elegant, and simple. That was Paul, his personality evident in his simple, strong prose with every word carrying its weight.

The words of students mattered too. Before each class, Paul would excerpt something from each of their response papers, some phrase that he would feature and use to spark some idea or another. Believe me, knowing that you could be so excerpted improved the student’s writing (and the thinking behind it) like nothing else would. Words were the stuff of ideas, and both mattered enormously.

Die in the saddle

At some point, Paul developed a serious lung infection. It affected him in ways that frustrated him. He was an avid rower on Austin’s Lady Bird Lake and commuted most everywhere by bike, both pursuits that require healthy lungs. Paul’s one reluctant concession was to buy an e-bike, which with Austin’s hills and heat is a reasonable choice even if your lungs are strong. Still, he was embarrassed by the bike’s motor, and reminded me that his model didn’t have a throttle, just a pedal assist. Too bad, I told him — a throttle sounds more fun. In our class, he would occasionally need his oxygen tank and sometimes lecture from home on his handcrafted lectern when the risk of Covid was high. But you’d hardly know he was ailing.

That Paul wanted to spend the last months of his life in the classroom became more understandable when I read his essay about dying, which he published in the The Washington Post shortly before he passed. He could have run out the clock, or he could have played hard right to the end. Paul chose to ignore the clock and grasp life aspirationally, taking on new projects even with the realization that he wouldn’t finish them. We may not know how we want to spend our sunset years, but for me, Paul’s example reminded me that at least some aspects of university life still very much matter at age 80.

Running out the clock would seem natural. But if you watch the end of a blowout game in football, basketball, and even soccer (tennis and baseball, which don’t have clocks, are different), you see something quite puzzling. Most teams facing insurmountable odds fight hard to the end even when it is mathematically impossible to win, often not even inserting their reserve players. There is no concession to the inevitable, like there is in chess. That valiant but futile fight has always puzzled me. But, I guess, what else are they to do? And it could be that, like everything else, the process is as important as the outcome. The feeling of leaving it all on the court in a courageous, dignified way is a wonderful one. Some of this approach to life that Paul exemplified — dying in the saddle, if you want — might be attributable to his military experience, a profession in which such an approach comes with the territory. Still, it now strikes me as the best way to go for civilians as well.

At some point I did ask Paul why he wanted me to teach his last class with him, a class at the very core of his expertise and so far from mine. He turned and looked at me and said, “somebody has to keep these ideas alive.” And so that’s what I’ll do. I’ll make room on my syllabi for Bartleby, Ajax, Agamemnon, and Billy Budd, among other literary characters so special to Paul. Many of these characters exhibited the same iconoclastic, courageous, and inspiring qualities that Paul embodied. And the stories are deeply satisfying to read, which is the point.

Zachary Elkins is an associate professor in the Department of Government at The University of Texas at Austin.