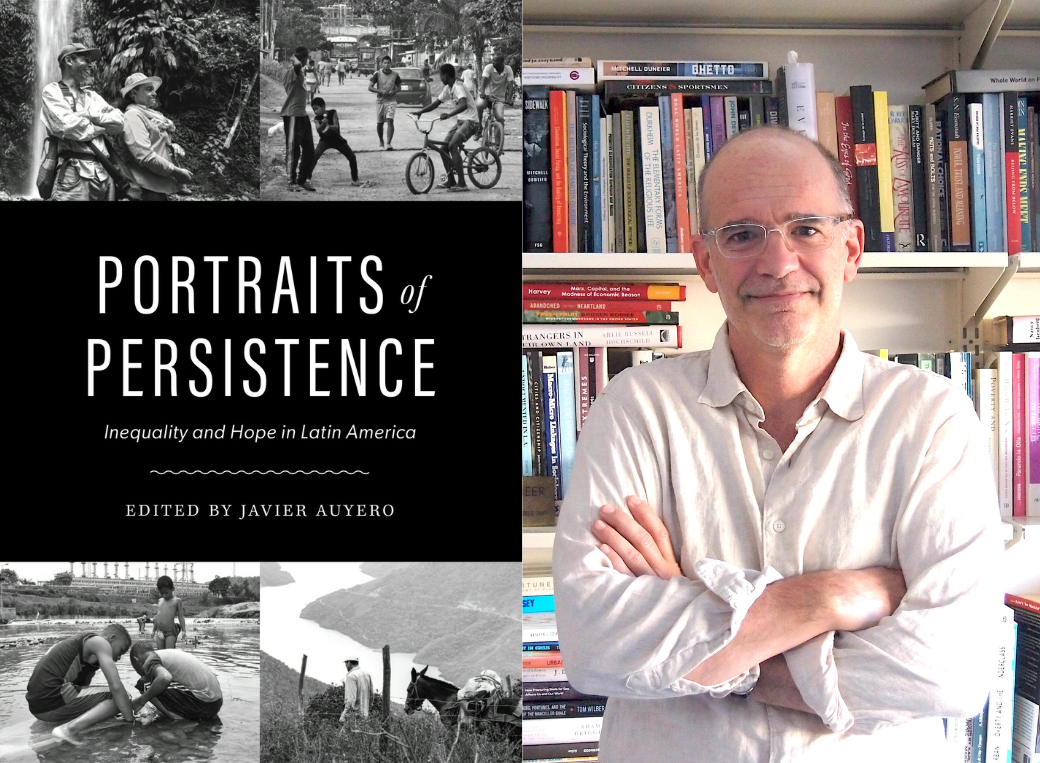

Javier Auyero on his new book, Portraits of Persistence: Inequality and Hope in Latin America

Javier Auyero, an award-winning sociologist at UT Austin, has led the university’s Urban Ethnography Lab since 2012. In the decade since, he’s regularly collaborated with the lab’s students and graduates on publications, including 2015’s Invisible in Austin: Life and Labor in an American City, a collection that captured the daily realities of Austin’s most marginalized workers and went on to be a best seller. The lab’s second book edited by Auyero, Portraits of Persistence: Inequality and Hope in Latin America, was published by UT Press this spring and presents twelve portraits of individuals struggling to build lives of meaning and purpose amidst inequality and injustice. By situating each life story within its broader sociohistorical context, the writers and subjects of Portraits offer unique perspectives into Latin America’s complex reality — and offer deeply compelling stories of lives shaped by hardship and hope.

Last month Auyero and I visited about the process behind the book, finding new ways to produce accessible and collaborative academic work, and the joys of intellectual fun. Read on for a lightly edited excerpt from our conversation, and learn more about Portraits of Persistence here.

I thought a natural place to start might be to ask you about your own research and your background, and then how that has led you to the ethnography lab and to this project.

I came to UT in 2008. My research has always been on issues of urban poverty, violence, collective action, for the most part in Latin America and specifically in Argentina, and always from an ethnographic perspective. That is the type of research in which you embed yourself within or as close as possible to the phenomenon you’re trying to study. I get as close as possible to what I want to understand, and I spend a lot of time in communities or groups or organizations.

When I came to UT, a colleague of mine, Christine Williams, suggested that we should try to group all the people at the university who were doing this kind of research. We were moving into a new building, and the thought was, why don’t we create this lab so that we can put the faculty and the grad students together working on issue. That’s how the lab was founded. The idea in principle was that this would be where all the people who were doing this research could gather and share projects, notes, funding opportunities, workshop papers, that kind of thing. But over the years, we started a common project. It started out of a graduate seminar I was teaching on poverty in the Americas. One day I assigned a book, which I love, The Weight of the World by Pierre Bourdieu, and the students didn’t like it. They were very critical. And I said, “Oh, you think you can do better? Okay, let’s try to do this better. How would you do this?”

That’s how Invisible in Austin was born. We combined sociological research with a new type of writing, this nonfiction or longform journalism writing. My challenge for the students was: you do research, you know these people, you hang out with them, you shadow them, you know them well, but your commitment is also to write them well. So, a student shadowed a sex worker and another shadowed a cab driver, another shadowed a homeless person, another shadowed an undocumented worker, and we wrote Invisible in Austin. To our surprise, it was published and it’s one of the bestselling books from UT Press.

After a few years, with a new group of students, I said, “We should try to do this again with our expertise in Latin America.” That’s how Portraits of Persistence was born. I called back a few of the old timers who are now professors, some already tenured, former grad students of the lab, some new students, and we put together this book. Again, the commitment was to know people well and to write them well, but what we really wanted to do is propose a different way of doing intellectual work that is more collaborative. In both of these projects, the students or my colleagues were not working under me. The idea was to work as horizontally as possible and to think of intellectual work as a collective enterprise.

Because of my own personal biases, which is that I was trained as a journalist and as a narrative nonfiction writer, when I was reading Portraits of Persistence I was really struck by how narrative and almost journalistic some of the writing is as you’re following these individual people. I’m not a sociologist, I’m not an ethnographer, I’m not sure how unusual that approach is, but it struck me that this is a really accessible and engaging way to present sociological work. I’d love to hear more about that approach to writing these stories.

For a long time, as sociologists, if you were accused of being a journalist, it was an accusation. It was like, “you are not doing sociology, you are a journalist.” But over the course of at least the last decade, a different way of telling our stories and the idea that we should write better has become much more legitimate. And there’s a model. I always tell my students, you want to know how to write? Okay, read Truman Capote. Read In Cold Blood or read Katherine Boo or read articles from the New Yorker. And Matthew Desmond, who’s a famous sociologist and MacArthur winner, won a Pulitzer Prize with a sociology book written in nonfiction. Jason De León is writing nonfiction. It’s not just us doing this. There is now more space, more legitimacy, to try different ways. Because it’s true that not a lot of people read sociology. It’s always a complicated story that we have to tell, and we don’t write that well. And both Invisible in Austin and Portraits of Persistence were a challenge because it doesn’t come natural to us to write this way and it requires a lot of work and workshopping.

Now we’re starting a new project, and the first thing we’re doing is having workshops with journalists from Anfibia Magazine who are telling us, “you need a character, you need a scene, you need a conflict.” And I say, okay, we need all that, and we also need a sociological story to tell. That’s the challenge because we’re not journalists and we don’t want to be journalists. We want to be sociologists but to tell stories or construct narratives in a different way.

There’s a very interesting debate that’s been going on for a while now that sociology should be intervening in public conversation, that we should be doing public sociology. How are we going to do public sociology if nobody reads what we write? I don’t know that we should engage in some sort of populist, like, “Oh, we should give them whatever they want,” but at least we should try to engage.

Portraits of Persistence tells twelve stories, and each has one or two main protagonists. How did you decide which stories to tell? Why these individual stories as opposed to others?

In Portraits of Persistence, the characters were very much determined by the larger story we wanted to tell. And this had to do with the expertise of each one of the contributors. First was, “Okay, this is my expertise. This is what my dissertation or my research is about. Can we find an individual who condenses or illustrates this?” And it’s a very old project for sociologists, this idea of sociological imagination or trying to find the intersection of biography and history. The idea wasn’t to be representative or “this is Latin America.” We are very clear that we’re not seeking to be representative. These stories illustrate some of the issues. There are many others, but we happen to know about these things. And the contributors were each like, “I know Myra, she can tell this part of the story.” I can’t remember exactly if we decided to say, “No, I don’t think this is the character you need. I think you better tell this other story.” But after we collectively ok’d these characters, then we tried to find a common style. And that took a lot of collective effort.

To strike that middle point between each writer’s individual voice and the cohesive voice of a group project — that’s a hard balance to find. And to do it with a project of this size and with this variety of voices and backgrounds and experiences, I can only imagine that that would have been really challenging.

It was challenging, but I have to say — and this is the advantage of working at UT — we recruit very, very talented students. I would be lying if I said I was a heavy editor. No, these students and professors know how to write. If you look at, say, Alex Diamond’s story of the two peasants in Colombia, we did some collective editing but the first pass was almost there.

And in some cases we had to do some editing because we all want to sound sociological. It’s like, no, you are doing the sociology, but tell it in a different way. Because of the pressures of the field, we still have to publish in sociology journals and write like sociologists, but this was a moment in which it was like, we can be someone else. We can still be sociologists, but we can liberate ourselves from this and we can play around with things. And I have to say, you say it was a lot of work and a lot of time, but it was also a lot of fun.

It was a lot of intellectual fun too, because we all knew that if all came out well, this is going to be a really important thing to have done. I genuinely believe that there is another way of doing intellectual work, and the ethnography lab and these kinds of projects are about this idea — and ethnography is sometimes very isolating because you’re alone in the field — that you never have to walk alone, that people are there. And we try to do this collectively, horizontally, because we love it. These days there’s a lot of bad words about academic work, that everything is terribly bad, it’s awful. Advisors are exploitative. Academia is colonizing. Everything is a disaster. I don’t think it’s all that bad, and you don’t have to take my word for it. This is what we do — take it or leave it, whatever. But this is another way of doing academic work, which is not exploitative, that is horizontal, that is collaborative. I actually believe that. I’ve been doing this all my life.

Is there one chapter or story from Portraits of Persistence that stands out to you? It might be like choosing your favorite child and you feel like, “I cannot answer this question,” which is fair.

No, no. But all of these stories have something. The predicament of this couple in Bolivia that has everything against them and they keep going. Or the couple in Colombia going through terrible threats from every possible source and they keep at it. Or the security guard in Mexico. I cannot pick one. All of them present some puzzle and some solution in the story. It’s hard for me to pick because all of the stories are there because they had some hook. When Jen Scott tells the story of this woman learning the transit system in New Orleans, just to feel some sort of freedom taking the bus and learning a city through the bus route, that was like, wow. And the place where they were living called the White House. I mean, it was beautiful. It was terribly sad, but it was also beautiful in narrative terms.

It’s fitting that in every example you’re calling out, you’re highlighting what you call persistence in this book, which is the common trait that each of these characters exemplify. You write that you organized this collection around this question of how people “put up with, perpetuate, or push back against the conditions that produce their suffering,” and you link that to this quality of persistence that they have. What led you to that question and to this theme? Did it rise up out of these stories? Or was that an idea that you had before the project came together?

The question about what, how, and why people put up with, tolerate, or resist has been a question for me for the last 20, 25 years of research. But that was a very general question, and when I put it to the group everybody had different answers.

Together with working on this project, I was working on my own research for Squatter Life and on the idea of strategies of survival. How do people make ends meet when neither the market nor the state can satisfy their needs? In dialogue with a colleague of mine at Berkeley, Loïc Wacquant, I was insisting on survival and assistance, survival and assistance, and he pushed me towards thinking that this is not just about survival and assistance. This is also about seeking meaning, making community, finding some sort of hope in the world. He’s the one who was like, “This is about persistence,” and we actually acknowledge his influence in the book. So, in that sense, the question organizing all the narratives was there from the beginning, but the idea of persistence emerged out of the process. It was a little bit more inductive, if you will.

And the title wasn’t obvious. It was Maricarmen Hernández, who wrote the story of Aurelia, who wants to build a house in a place she knows is highly contaminated. She’s the one who said, “We are actually creating portraits. I think ‘portraits’ should be in the title.” So we had Portraits for a while, but it was just Portraits. We didn’t know of what, but then Portraits of Persistence had a ring. But it wasn’t like it was my idea.

What you hope that readers of this book take away from it, both academic readers and a general audience? And then — this seems like the natural question to end on — what’s next for you and for the ethnography lab?

I have a very modest hope, which is that people read it, enjoy it, discuss it, and learn something about the countries and that that piques an interest of like, “oh, I want to know more about this,” or “I want to know more about that.” That’s very important, very basic. If they learn a different slice, a different way of entering Latin America, better. If they can learn one thing or two about, “oh, it’s not just pure domination or pure suffering, it’s about other things,” then much better.

What’s next is we’re doing, we don’t know if it’s a book or what, but we’re doing this project on things that work in three countries in Latin America. It’s about community grassroots initiatives that started out of contentious politics and social protest but last and then make a difference in poor marginalized communities. It’s something that is actually making their lives better. We’re doing this with a group of students and now, from the start, with the help of journalists who are telling us, “This is how you write.” The students are now doing the first bit of field work and we eventually will publish the stories and apply for more funding. We’ll see. It’s about having fun. This is, for me, intellectual fun.

This essay was originally published on Extra Credit, COLA’s Substack newsletter. Learn more about Extra Credit and subscribe here.