When I arrived in graduate school at The University of Texas at Austin in the late 1970s, Austin felt like a foreign land to me. I was coming from South Texas, where I’d grown up and also gone to college. As it is today, UT was linked through faculty and students to major social issues and developments across the country and the world. National and worldwide movements had a

presence on campus through members and allies of the women’s movement, the Black movement, the Chicano movement, the American Indian movement, and others.

There was an optimistic sense among many students on campus that we had broken with the old tenets of class, race, and gender and entered a new social age. The bookstores on the Drag helped nourish this sense of liberation, with books on critical philosophy and radical political economy by theorists like Hegel, Foucault, Marx, and Luxemburg. The Co-op had shelves of new books filling two floors. Sociology, anthropology, economics, and philosophy were popular majors to understand the social change of the day.

Part of the student experience is common to all students, but each student also intersects with the zeitgeist on their own terms. One unique project I became involved with as a graduate student in sociology was organizing a school in East Austin for undocumented Mexican children. At the time, public school districts in Texas did not accept undocumented students, so on school days one could see Hispanic immigrant children playing in the streets on the east side when they should have been in school. I thought it was a social injustice not to provide an education for small children in their prime learning years. I believed education to be a human right. I wrote a short op-ed on the topic in the Austin-American Statesman, for which I received hate mail in response: “Go back to Mexico with your illegal alien friends,” one letter said.

With a couple of other UT students and volunteer bilingual teachers, we organized a school for about 60 undocumented children. We borrowed an unused building at an east side church and in halfday classes taught the children English, geography, and history, among other topics. In the evenings we used the school to teach the children’s parents how to read and write in English.

The school project opened an avenue for me and other graduate students to do research in the Mexican immigrant community. This was a major resource for our research on immigrant integration that we were conducting with a professor at the Population Research Center (PRC) at UT (it was PRC faculty who had recruited me to the sociology department in the first place).

It was an incredibly stimulating intellectual environment for me. I remember one professor at the PRC, Harley Brown, who was working on building a library of censuses from countries across the world. This may sound unnecessary now, in the age of the internet, but in the 1980s the digital world of easy access did not yet exist. All data existed in physical form, and there were very few libraries in the country where researchers could review the censuses of the world in one place.

I still remember the day the first desktop computer arrived at the PRC. Faculty and students gathered around the white box and monitor to marvel at its functions. Only the head PRC administrator was allowed to touch the computer, but the days of the IBM Selectric II typewriters on campus were clearly numbered.

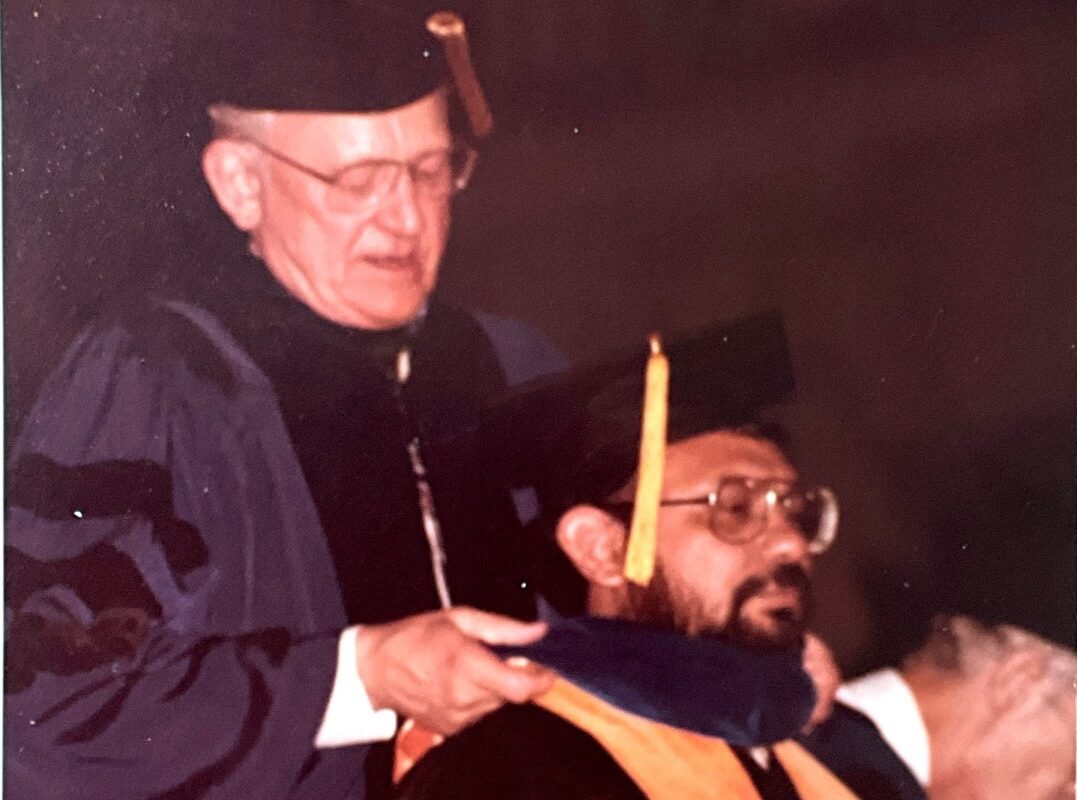

I developed a habit of visiting the PRC census library every Friday afternoon, and it was there, one Friday, that I found my dissertation topic. I took a book off a shelf about labor-force data in Europe, and I noticed that several European countries had similar percentages (8 to 12%) of foreign workers in their labor forces. The figures revealed a pattern: advanced capitalist societies of the West used foreign labor from less-developed countries as a secondary segment of their economies. This fact may sound like common knowledge now, but in the social sciences of the ‘80s we still did not have good theories to fully explain its significance. The relationship between capitalism and migrant labor became my dissertation project. In the spring of 1984, some 499 pages later, I graduated with my Ph.D. I left for the University of Houston to begin an academic career focusing on international migration that eventually brought me back to my home department at UT in 2008.

Nestor P. Rodriguez is a professor in the Department of Sociology at UT. His research focuses on Guatemalan migration, U.S. deportations to Mexico and Central America, the unauthorized migration of unaccompanied minors, evolving relations between Latinos and African Americans/Asian Americans, and ethical and human rights issues of border enforcement.