Hank was, admittedly, not a perfect political candidate. But he just may have been perfect for his time and place — namely, early 1980s Austin.

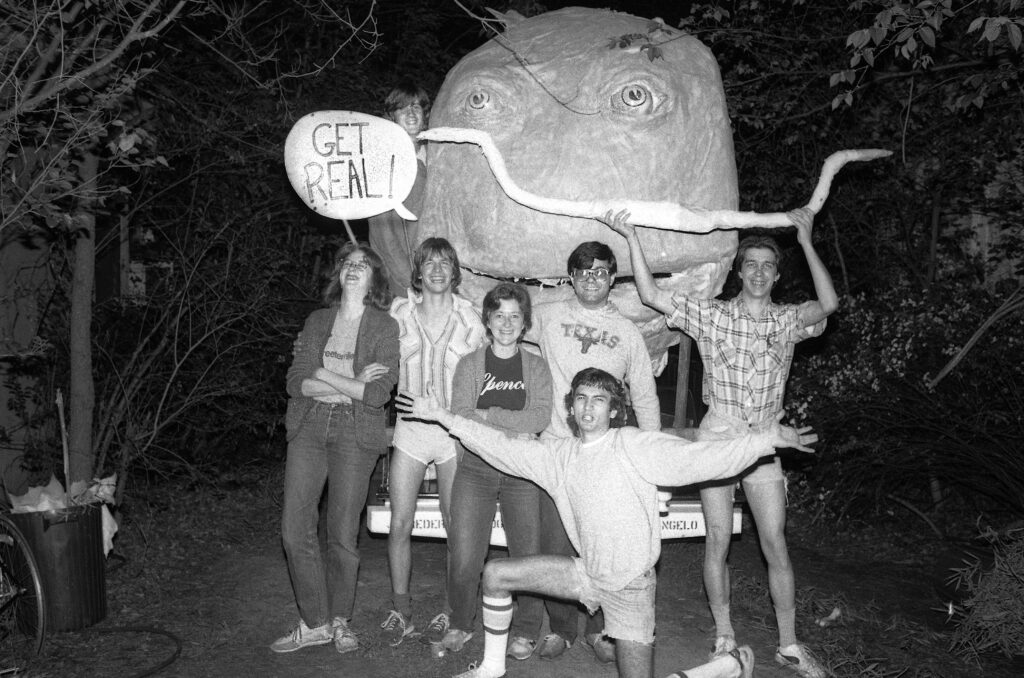

Hank was already popular around The University of Texas at Austin campus before he entered the race for president of the Students’ Association in the fall of 1982. On a campus where many were skeptical about whether it was even worth having a student government, Hank’s laid-back, irreverent campaign — his slogan was, simply, “Get Real” — resonated with ambivalent voters. Pro-Hank flyers popped up around campus. Campaign buttons and T-shirts quickly became hot commodities. Supporters put on a concert/political rally, “Hankstock,” on the East Mall and bought political ads in the Daily Texan.

Because Hank hadn’t managed to get on the ballot, his backers called for voters to write in his name. And the voters responded: On Nov. 10, 1982, Hank pulled off a decisive victory, with 3,013 votes — more than the combined total earned by the second- and third-place finishers in the race.

There was just one problem: Hank couldn’t take office. Because Hank not only wasn’t a UT student — he wasn’t even a person, but a character in a comic strip.

More than four decades later, piecing together the precise details of the rise and fall of Hank is a bit tricky; the key players, who’ve gone on to distinguished careers in politics and law, journalism and the arts, education and business, all remember things a little bit differently.

That might be a function of the fact that, even at the time, Hank’s campaign meant different things to different people. Was it a trenchant commentary on the absurdity of the political system? A fun goof cooked up by a bunch of third-year law students with too much free time on their hands? Or maybe some combination of the two?

Certainly, the campaign cannot be uncoupled from the political mood in Austin at the time. In the post-Watergate, post-Vietnam climate of skepticism about political institutions, many students questioned the usefulness of government in general and campus government in particular. To critics, the Students’ Association was a charade, an opportunity for politically ambitious students to boost their CVs without exercising any real power or making any real change.

That sentiment had been manifest in the 1976 election, when Jay Adkins ’78 won the presidency on the “Art and Sausages” ticket. Adkins (in a campaign-trail uniform of mirrored sunglasses and a top hat covering his long curls) and running mate Frederick “Skip” Slyfield ’77 (long hair, bushy beard, shmatte) ran on a self-declared absurdist platform that had distinctly Merry Prankster vibes; one of their promises was to change the motto engraved on the Main Building from “Ye shall know the truth and the truth shall set you free” to “Money talks.” (Adkins went on to get a law degree from The University of Texas at Austin School of Law and served as a judge before his death in 2019. Slyfield is a retired airline pilot.)

UT student government (and the original Main Building motto) survived the reign of the Art and Sausages party. But by 1978, anti-government sentiment had built to a point that the majority of students voted to do away with the institution entirely, and the Board of Regents formally abolished the Students’ Association.

Not everyone was happy with that decision, of course, and in October of 1982, another vote took place, this one to restore student government. The motion passed, by a vote of 1,701 to 1,178, and a new field of candidates emerged for the election, to take place the following month.

Among the contenders was Paul Begala ’83, a government major who at the time was interning at the Texas State Capitol with then-state Sen. (now-U.S. Rep.) Lloyd Doggett. To say that Begala believes in the value of government is an understatement; for evidence, see his subsequent decades-long career in politics, including as an advisor to President Bill Clinton and, more recently, as a national political commentator.

The students who voted to abolish the government, Begala recently recalled, “decided that student government was useless. And, worse than that, it was just a resume-padding device for future politicos and had no connection to their lives.” But doing away with the government, he said, was short-sighted. “Power is like matter in the universe: It doesn’t go away, it can’t be created, it can’t be destroyed. It just moves.”

In this case, the students’ power — including the power to decide how revenue from student fees would be spent — moved to then-UT President Peter Flawn. “There was this giant pot of money, student money, that the president was spending without any student input,” Begala said. “It was $7 million a year. And he just spent it as he saw fit.” To address that, Doggett shepherded through the state legislature a bill forbidding the president from spending that money without student input. A student-fees committee, on which Begala served, was created.

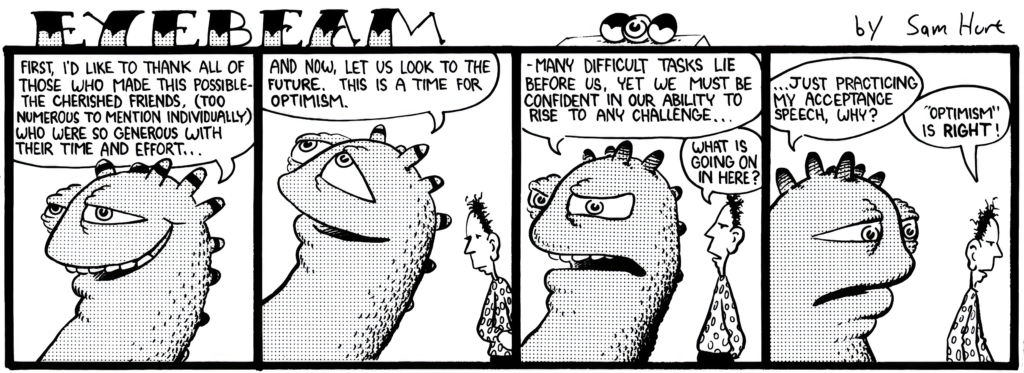

“We now had input into how that money was spent, but that wasn’t good enough. We wanted to control it,” Begala said. So, he and like-minded students began agitating for the reestablishment of the Students’ Association. “This became a debate between the nihilists and the sort of ‘government types.’” After the October vote to reinstate student government, he jumped into the race for president, along with two other students — and one comic-strip character, named Hank the Hallucination.

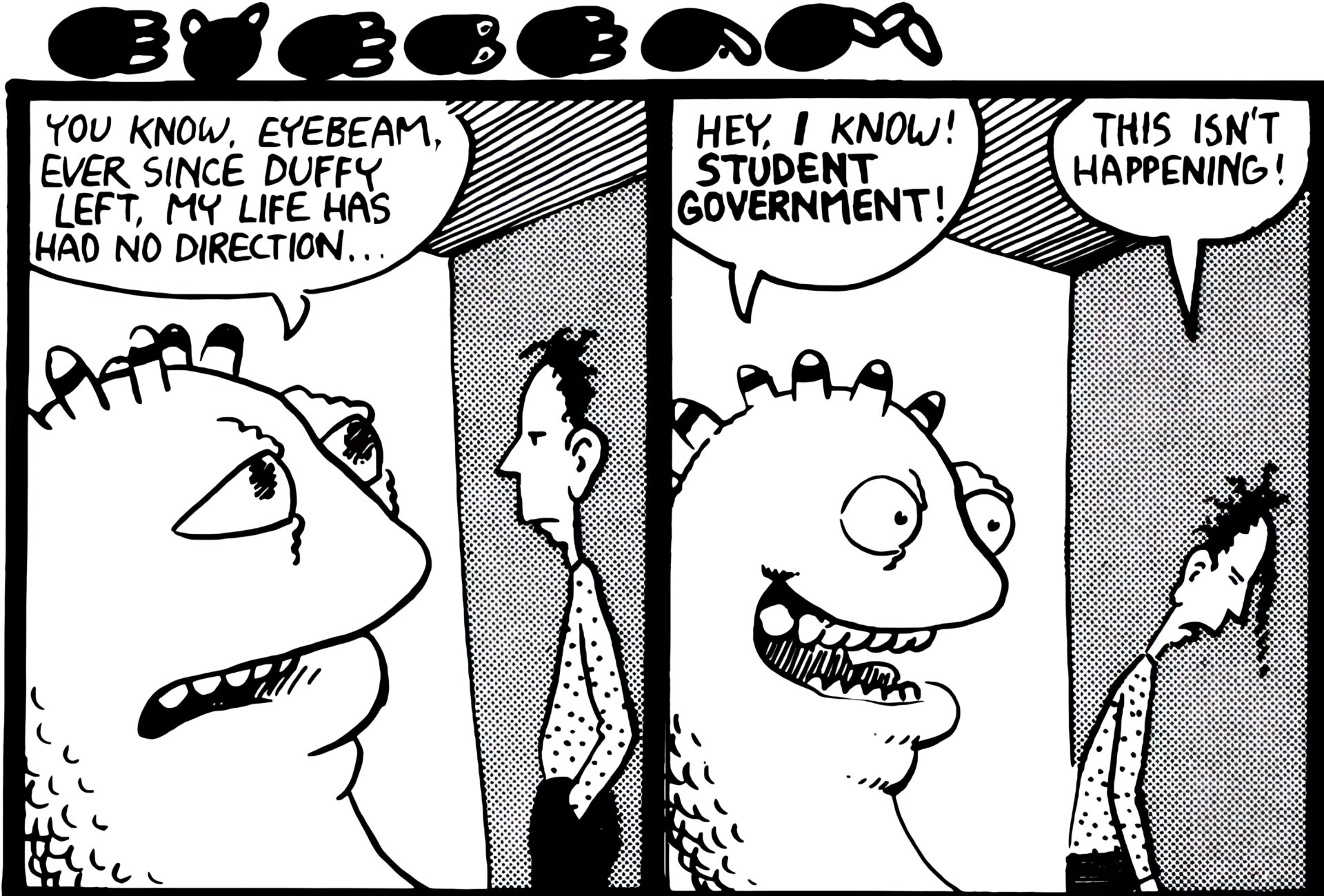

Hank was the brainchild of Sam Hurt ’80, the creator of the popular comic strip “Eyebeam.” Hurt began writing the strip, which focused on the semi-autobiographical title character and his quirky cast of friends, during his undergrad days. By the time he enrolled at the UT School of Law in 1980, the comic was running every day in the Daily Texan. (Hurt still writes “Eyebeam,” now for the weekly Austin Chronicle.)

Hank the Hallucination, a cheery, monster-like character whom only Eyebeam could see, was a favorite of readers. “I’ve always been attracted to kind of weird, out-there stuff,” Hurt said. “The earliest incarnation of Hank was on a Father’s Day card I drew from my dad. … I thought: Well, he’s fun to draw. So I put him in [the comic] and just had a lot of fun with the concept of a character who’s nonexistent, who’s imaginary.”

One day in the fall of 1982, Hurt and a few friends were relaxing in the lobby of Tarlton Law Library when the conversation turned to complaints about the revival of the Students’ Association. “And someone said, ‘Sam, you should run to be the president of the student body,’” Hurt recalled. “I had absolutely no interest in that. Then somebody said, ‘Oh, you should run Eyebeam.’ And that was kind of fun to think about. But then I hit on that if any of my cartoon characters were to run, it would be Hank the Hallucination.”

What made Hank the ideal candidate? “Within the imaginary world of the strip, he was an imaginary character,” Hurt said. “And there was just a lot of material to play with. It was just a fertile source of material for me.”

Hank also proved a fertile source of campaign material. Steve Patterson, a law school classmate of Hurt’s, stepped up to serve as Hank’s campaign manager. Patterson was in the camp that opposed reviving student government, which he saw as a meaningless, powerless institution. Hank, he said, was a perfect candidate for the job: Who better to run for an illusionary government than an illusory character?

“We’re a bunch of third-year law students, and we’re obviously convinced we’re the smartest people on the planet, right?” Patterson recalled with a laugh. “We know more about governance and the law and how to run a bureaucracy than anybody else on the planet. … And every time somebody would say, ‘But you can’t get on the ballot,’ or ‘You can’t win; you can’t take office,’ well, god-damn right we will! No matter how delusional we might have been, we were convinced that the other side was far more delusional.”

The meteoric political career of Hank the Hallucination made sense in the groovy, whimsical Austin of his student days, said John Schwartz, a law school classmate of Hurt’s and his editor at the Daily Texan. (After a career writing for Newsweek, the Washington Post, and The New York Times, Schwartz returned to UT to teach at the School of Journalism and Media, now known as the Moody College of Communication.)

“It’s why people remember the ’70s and ’80s in Austin with such terms of affection: Anything could happen. Everything was funny,” Schwartz said. “It was a great time to be in Austin. It was a great time to be a student.”

In particular, it was an environment ripe for a mock political campaign. “Politics was fun and making fun of politics was fun. That’s much grimmer now,” Schwartz said. “Once something like that started rolling, it was just unstoppable. All of a sudden people had a reason to vote.”

Of course, not everyone was charmed by the Hank campaign. “People were mad about it,” Hurt said. “There were very, very angry letters to the editor, that we were making a joke out of this serious thing. It just stirred up a lot of passion.”

The campaign played out in the comic strip as well, mirroring Hurt’s real-life experience as Hank’s creator. “It became overwhelming, with all the press and my phone ringing all the time,” he said. “I had my character Eyebeam dealing with a similar situation and, true to the cartoon medium, I could exaggerate it. That’s one of the fun things about cartoons, you can just kind of go over the top.”

Looking back, Hurt speaks about the campaign with some ambivalence. “It started off as a gag and really took on a life of its own,” he said. “I was surprised, I was delighted, and I had misgivings about it. I loved the attention to the strip, so I wanted to believe that it was a worthy cause. I wanted to buy into that, but I always felt a little conflicted about it. … There were some people that were really against the whole idea of student government, which is kind of confusing to me, looking back on it now. Why was that such a bad idea?”

All these years later, Patterson (who went on to a career in sports, including as athletic director at UT and as general manager of the Houston Rockets and Portland Trail Blazers) can’t quite remember the specifics of Hank’s platform.

“I mean, whatever platform it was, it was totally fake and bogus. But it worked,” said Patterson. In an election that saw what the Daily Texan reported the next day as an “unusually high voter turnout,” Hank secured 47% of the vote, with more than twice the number of votes of the second-place finisher, business major Pat Duval. “And amongst the hallucinatory vote, it was a landslide,” Patterson said. “I mean, the pixies and the fairies came in overwhelmingly for us.”

Were Hank’s supporters surprised by his victory? “No, we were not,” Patterson said. “We fully expected it. It was just a mix of anti-establishment, silliness, fun, and attention-grabbing. We’d have tables on the West Mall and just get swamped and sell out of T-shirts and sell out of bumper stickers. Everybody wanted to be at the events, like Hankstock.”

“I think people just like the surreal,” Hurt added. “And college students are facing this pressure: the academic pressure, the impending adulthood hanging over their heads. ‘I’ve got to get this schooling done and go out there in the real world and get a job.’ There was just a big appeal to this crazy party.”

But even the best parties come to an end. While Hank’s supporters were celebrating their victory, the university’s election commissioners announced that there would be a runoff between the second- and third-place finishers, Duval and Begala. Hank, being a fictional character, would not be included.

While the Hank camp put up a bit of a protest, they were ready to let their campaign wind down, Patterson said. “We were all graduating and leaving and we couldn’t keep this farce going any longer. …. We had made the point. And we weren’t misguided enough to think that we would actually go try to [take over].”

The runoff went ahead. “Now then the thing became: Who’s gonna get the Hank vote?” Begala said. “So I promised to build a statue of Hank on the West Mall. I just basically went out one day and waved a sheet and said, ‘There he is, everybody.’ … And I maintain if you go there today, with proper inspiration from 11 herbs and spices, you can still see Hank. He’s right there; you could still feel his spirit and see him if you’re properly inspired.”

Whether due to his Hank tribute or to other factors, Begala went on to win the runoff and become president. “It was fun watching Paul Begala get involved,” Hurt said. “He was very astute, the way he got in on the joke. He ran against Hank with a wink. … I was like: This guy’s smart. Strategically, he made a good choice by seeing the fun in it.”

But Hank’s supporters still needed closure. “We were playing off of all the different things that happened to politicians,” Hurt said. “Somebody had written some fanfiction about an assassination attempt. And it got me thinking: Since Hank was imaginary, what would happen if someone tried to assassinate him?”

The answer: It depends. First, Hurt drew a strip in which Hank and Eyebeam were walking across campus when they were confronted by a man with a gun. “Eat lead, pinko fascist hallucination,” the gunman said as he opened fire — but to no effect. “Because he’s imaginary, a real bullet can’t touch him,” Hurt explained.

Alas, Hank’s luck soon ran out: In the next day’s strip, as he was celebrating his escape (“Pretty good deal! That assassin’s bullets went right through me! He couldn’t even see me!”) Hank happened upon a little girl, who pointed her finger at him and said, “Bang, bang!” As it turns out, imaginary bullets can kill an imaginary creature, and Hank promptly vanished. Around the same time, Hank was also assassinated in real (or, rather, “real”) life at an inaugural ball thrown by supporters, when crashers stormed the party and killed an oversized paper-mache Hank.

While Hank’s political career ended with the double assassination, the laws of the comic-strip universe turned out to be more forgiving. “In the strip narrative, he came back, and I had a lot more fun with him as a character,” Hurt said. “He was only briefly assassinated.”

Losing an election to an imaginary character, as it turned out, did not turn Begala off politics. In fact, Begala said, that long-ago student government campaign taught him lessons that he still carries with him. “I’m not kidding. It’s guided my whole political career. Those two words ‘get real’ taught me a lot.” It taught him not to take himself too seriously, but to take the work of government — to create real things for the benefit of real people — very seriously.

That became Begala’s focus during his term as Students’ Association president, he said. “When we came in, we were really determined not to do anything self-serving and not to do anything simply symbolic. There’s a lot of symbolic politics in this world, and I hate it. So we didn’t declare the campus a nuclear-free zone. We didn’t declare our solidarity with the people of El Salvador.”

Instead, Begala’s administration — which included his now-wife, Diane Friday — used the student-fee funds to create a campus recycling program, a childcare center for student parents, and a security program that provided escorts for students walking on campus late at night. He also used his time in office to help defeat proposals to increase tuition and to raise the drinking age. (“That made me very popular.”)

“The most important thing [was] to make a difference in people’s lives, to show them that this was not just about padding your resume,” Begala said. “That was always our North Star.” While he might have developed that philosophy anyway, he said, the 1982 election crystallized it. “Hank got more votes than I did. And he was just saying: ‘Get real. Don’t be awful.’ That’s how I interpreted it, anyway.

“That really did guide me,” he continued. “I had the pleasure and honor of working in the Congress and in the White House. And there was always that question: What are we actually doing to make a difference in people’s lives?”

Hank’s campaign, Begala said, “was fun and funny and creative.” Indeed, he added, “I might have voted for Hank, if I hadn’t run.”