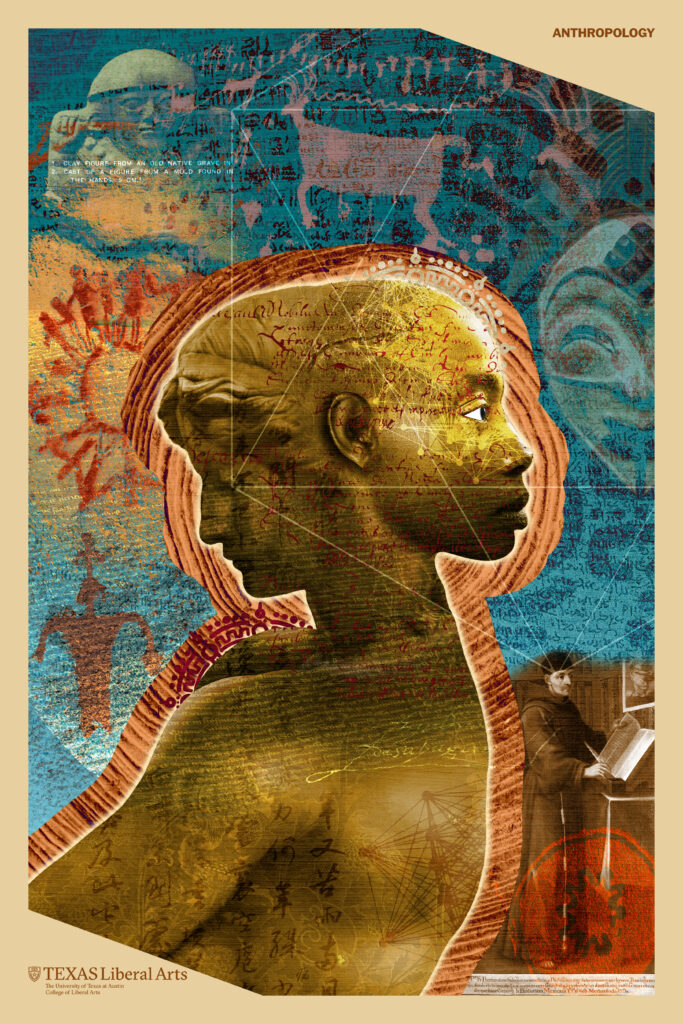

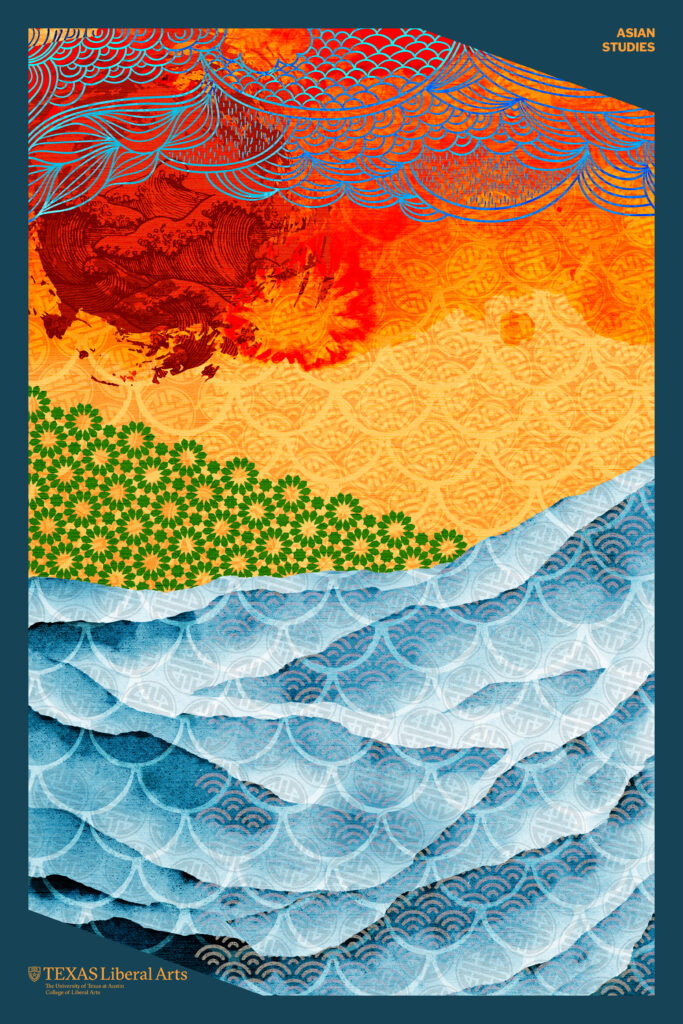

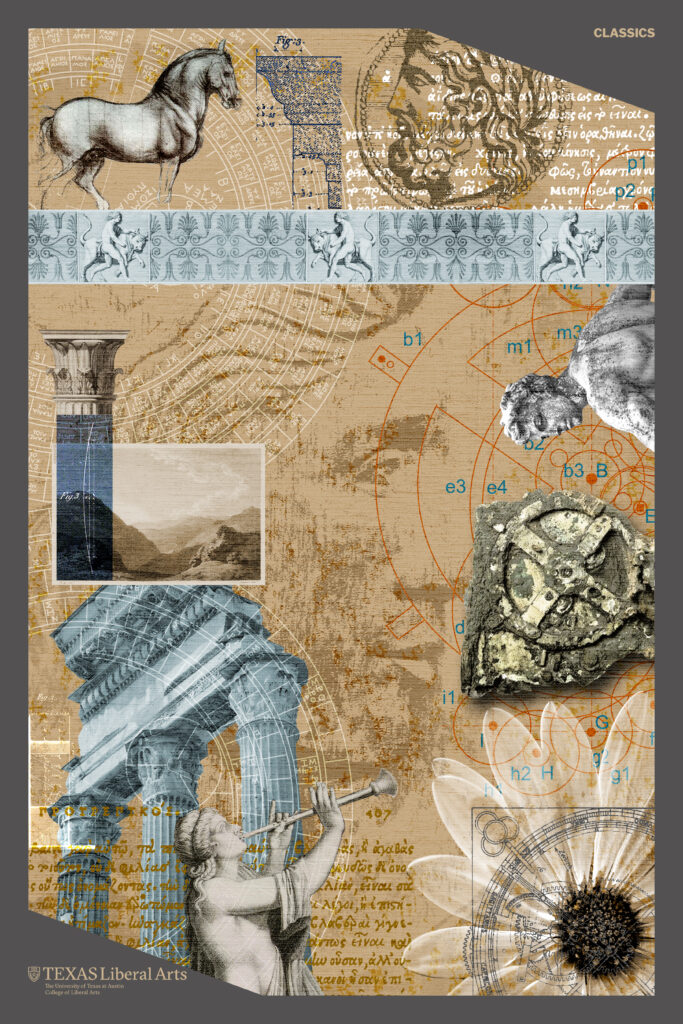

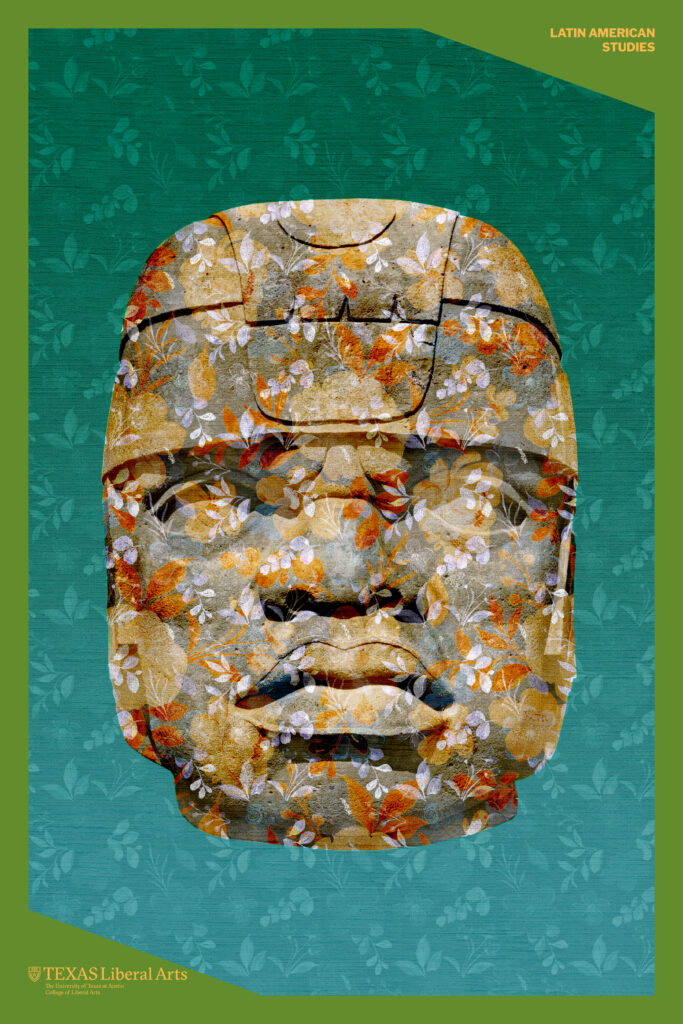

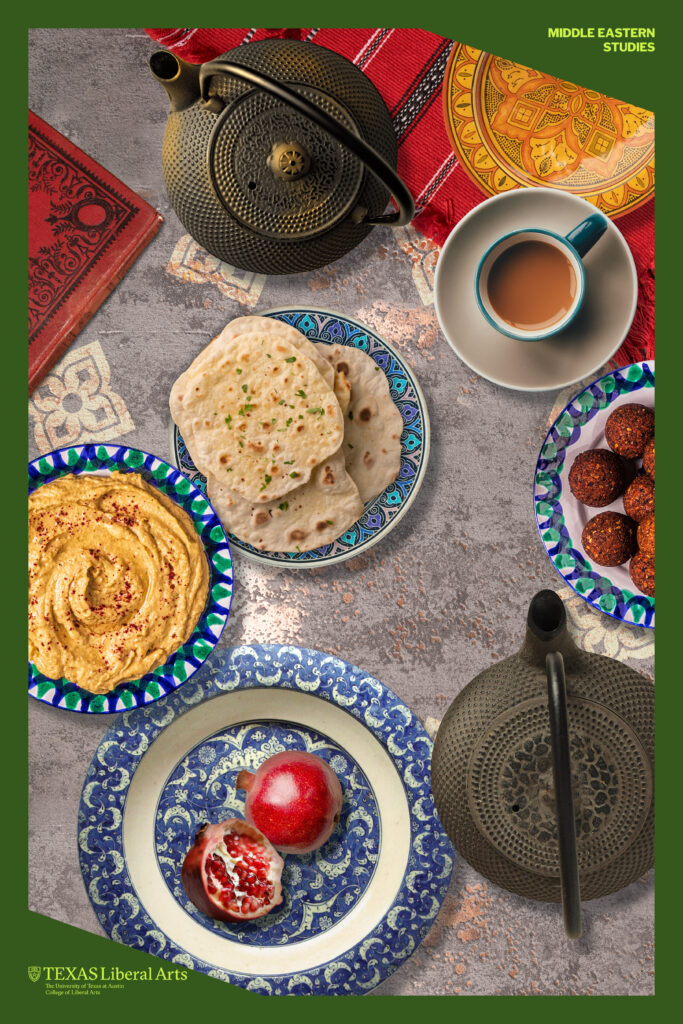

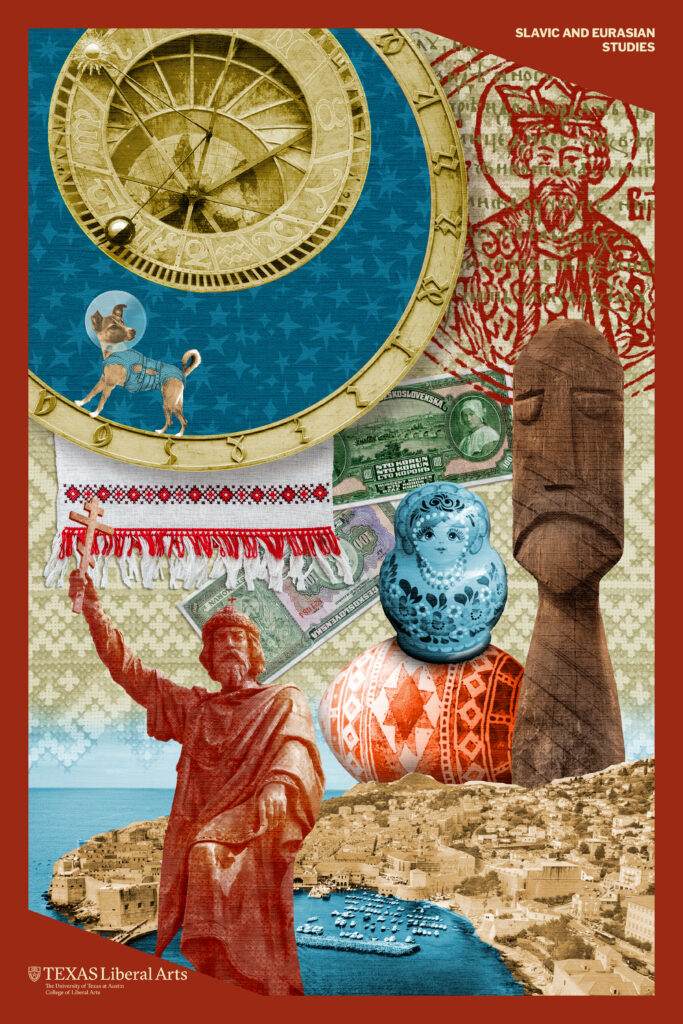

In an effort to spiff up COLA’s main administrative building, Dorothy Gebauer Hall, the college hired the very talented Dave McClinton last year to design posters for each of our departments and a handful of our interdisciplinary programs. Given the breadth of topics and fields that the college teaches and researches, creating a cohesive visual campaign was always going to be a challenge. But McClinton was up for the task, and if you ask us, he knocked it out of the park.

Earlier this year we caught up with him about his process for the project, how he makes his art, and his creative influences. An edited version of that conversation follows, along with a preview of the final poster designs.

Tell me about your art. How do you approach your projects? What’s your motivation?

My projects are all different. I approached this particular project as a hybrid of design and art. I felt like the posters all had to fit a certain style, so I wanted to create a footprint, a pattern, where if you took off all the College of Liberal Arts branding, and you had two or three posters next to each other, you would think, “Oh, the same idea is at hand here.”

I’m trying to show details that when you look at them, you think “I’m in the Liberal Arts building.” I liked the idea that if you know about history, or if you see something that piques your interest, you might go Google it.

It’s research first, and that’s true if I’m designing a logo, a poster, or art. I like to find little nuggets that hint at an era, a culture, or an idea that then pulls you into whatever that particular piece is about.

How did this project fit into your work in general? Is that how you approach your design work and your art?

It always starts with something that needs to be communicated. For instance, with these posters, I wanted to find what made each particular poster and work of art unique to its department and I wound up doing some deep dives. For the Asian Studies poster, for instance, I didn’t want to just slap up some language that doesn’t represent the entire region, so I researched the origins of Asian languages. I went all the way back and I found a tablet that predated Sanskrit that was the origin of all the languages in that region, so that’s what I used. No one’s going to look at that and go, “Oh, I know what that is” — it’s that 10,000-year-old dead language,” but that’s the type of research I’m talking about. Or, I was trying to find who the father of philosophy was, and then found out there was a mother too. I get into all this kind of stuff and I want to represent that. It’s always a deep dive to make sure the idea has resonance and a toehold in reality, and isn’t just a whimsical sort of thing.

Tell us about your design and art background. Where and how did you get your start?

When I was in school, I was on the fence between being a design major or a fine arts major. I was going to school at Incarnate Word college in San Antonio, then I transferred to Texas State University. I was taking design and art at the same time and trying to figure out if I wanted to go into the job market as a designer or if I wanted to stay in school and have some sort of life as an academic or an artist.

I made a practical decision and try to get a job. That’s just how I was raised. I was raised by a career Air Force father and my mother taught Sunday school, so, as you can probably imagine, I was raised to be a practical person; I chose the job route.

How does how you were raised impact the themes in your work and the way you approach the art that you make?

The art that I make centers around what it’s like to be Black in America. It’s about cultural things specific to my upbringing and my people. My parents were brought up in the Jim Crow era in Texas, where there were colored drinking fountains and they went to segregated high schools. My dad is from Seguin and mom is from New Braunfels, basically 13 miles apart, and back then just about every Black person in Seguin knew every Black person in New Braunfels. There was a real sense of community because you never knew when you’d have to be on the run.

They raised me on a fence between, “don’t stick your neck out because it might cause a problem,” and at the same time telling me, “You can do whatever you want to do.”

So, I walk this fence, trying to make my way with both those thoughts in my head. That very much influences my art. And I also feel lucky that my parents were so accepting of me becoming a creative because there were a lot of more traditional things that they could have directed me toward. My dad rolled his eyes a little bit because he knew I was going to be 6’1” and 250lbs, and well, that’s a linebacker, not necessarily an artist. And then there’s the macho thing of the Black male, that sort of thing. But it didn’t take him long to be like, “that boy’s just going to do what he wants to do.” They were very open to me doing something creative. Parents may want you to get a practical job because they’re terrified of what the world might do to you if you’re trying to be creative, at least in my generation.

That also influences my art in that I feel like I have to be exceptional at it because of what was sacrificed for me to even be able to go to school and to do this for a living. It feels like, not a burden, but an honor to need to be successful and good at this thing that I’m lucky to be able to do. In terms of style and topic, it’s culture, it’s civil rights, it’s trying to paint a picture of what it’s like to be us.

How do your folks react to your work? What’s the feedback do you get from them?

When it was graphic design work, it was always hard to explain to my parents specifically what web design or branding was. In their minds, I was just sitting at a computer. But when I had my first art show, that was different. My mom pulled out all these drawings and paintings I’d done when I was a kid that I’d forgotten about and she found this photo of me wearing my dad’s big Air Force shirt backwards, like a smock, because I was painting. This theme was there since I was little. When I had my first solo show at the Dougherty Art Center in 2018, my parents came to see it, and it was their first time to see that side of me in a real-world situation: We were in a gallery, my friends were there, colleagues were there, and my name was on the marquee. And my dad walks up, and he sees my name there and he just looks at it, then looks at me and he goes, “How about that?” He might as well have shot fireworks up in the air. I knew what that meant.

What is your day-to-day design life like?

I have a day job with Sundaram Design. It’s client work, a lot of branding. Nobody else in the firm wants to do branding and I love branding, so it’s a perfect fit. I get to do all the logo projects, like right now I’m working on school sports mascots.

And then I also try to carve out time to make my own personal artwork. Every day there’s something creative happening or some sort of research happening or communication with a client about what they’re looking for.

I do a lot of work trying to represent something for someone else. And with my personal work, I’m just representing me.

Who are your favorite types of clients?

The clients that trust me out of the gate are the best ones. Because they’ve had experience, or they’ve looked at my portfolio. They understand I know what I’m doing and they’ve worked with the designers before or artists before.

Trust and communication make a great client. When a client wants to work with you again, or they trust you enough to refer you to someone else, those two things are gold. I’m doing a project for someone in a museum right now who just knew me and trusted my eye and my artwork. And now she’s in a position to send me work, and it’s that sort of that trust that gets built up over time that’s so gratifying.

Who are some of your creative influences?

Too many to truly list, but here’s a few: Egon Schiele — his line work and texture are so expressive and honest; Nancy Spero — her work is not exactly protest art but it expresses its truth aggressively; and Michael Ray Charles — he’s a multimedia artist who explores racial stereotypes and Black caricatures.

Do you ever hit a creative block? And if so, how do you get through it?

I read a quote from J.D. Salinger, talking about when you get writer’s block — same thing as a creative block — you just sit down and start writing. And I’ve heard a lot of writers say that. I just start researching. I know I have to make a poster for the anthropology department, so I start researching what represents that and then just keep digging up source material. Whether it’s written or imagery, the ideas come from doing, from gaining the knowledge about what it is you’re designing. That gets you past the block. In fact, I would argue that there are no blocks because you simply follow the research, follow what the client wanted and follow your ideas.

I just start pulling images. It could be anything. I saw a cartoon the other day and I remembered something I used to say as a kid: “Heavens to Mergatroyd.” And I wondered, “what was that?” So, I looked it up, and now I have names and historical figures and lines of poetry that came from just that childhood memory of that cartoon that spin into art ideas.

A friend of mine was talking about his mother, that she was a seamstress when he was a kid. And I like wordplay, so I split that in half and she “seemed stressed” trying to raise money to support her family. That conjures up an idea of a hardworking Black mother. I immediately get images from that.

The audience for this poster project is primarily faculty and students, but we also have prospective students coming through our buildings and parents and alumni visiting. Is there anything you want this audience to understand about your work or about this project that goes beyond just what they’ll see visually?

I want them to understand that it’s a digital collage pulled from many different sources. When you see faces, unless it’s a historical figure, it’s an invented face, with an eye from one place, a nose from another. The military science poster, for example, I had to build the hat from scratch. I had to find a naval hat, find the right leaf that goes here, find the right emblem that was correct for the Navy and not just armed forces in general, because they have little details that are different, and they have to be correct.

And then, even deeper, there’s this spiral etching coming out from the eye of the astronaut; that’s the etching that’s on the Voyager. There’s this gold record that was placed on the Voyager. Someone will find that and be able to decipher what those things mean if they’re a NASA nerd.

I want people to think about the source material. I’ve got supply and demand equations on the economics poster. I’ve got the symbol of the statue of Columbia, which was pulled from one of the first stock certificates ever. There’s this ‘X’ of wheat I have in the corner of because that was one of the first forms of currency.

I’ve got things in there that I dug to get, and I want people to notice all the thought and sourcing that went into it. Every little thing they see has a purpose. All these details are fun for me. The details matter. They weren’t just chosen randomly.

Thank you for bringing that level of research and thought and integrity into every piece of this project and all the work you do. That’s why we wanted you on this project and why we knew it would be successful.

It’s been fun and I’m proud of the work. Some of these are brightly colored. Some of them are muted, but they all feel like they belong together.

There is a rhythm that happens and a momentum, like I do one and then I dive into the next one and then it really starts to flow because I get back into that mindset. It just tickles everything I love to do. There’s the image making, the research, the connecting of dots, looking for wordplay. I just love all those things and in this project it’s all there.

We’re so glad we could bring you some value in the project. We’re a finicky client…

There’s another one! I know what that word means, but now I’m going to have to look it up. I need to know the origin of the word. I need to know how it’s been used in slang. It’s usually applied to cats. When I was a kid, only cats were finicky. So now I’m going to deep dive into the source.