It’s a good moment for Native American and Indigenous literature, says English professor James Cox. Lately, Native writing has exploded in genre fiction — like mystery, science fiction, and horror — and while it’s fair to say that Native American literature is still a small field, work by Native scholars and writers has had an outsized impact in the U.S. in the last 10 years when it comes to winning major literary awards and cultural recognition.

Cox would know. The co-founder of the college’s Native American and Indigenous Studies (NAIS) Program, he’s written or edited four books on 20th- and 21st-century Native American literature and the history of Native Americans in American literature and culture.

He credits some of the increased visibility of his discipline to the recent proliferation of Native stories in popular culture: shows like Reservation Dogs on FX, whose creator Sterlin Harjo just won a MacArthur; Disney’s miniseries about Marvel’s Echo character, played by Menominee actress Alaqua Cox (no relation); or the movie Prey, dubbed in Comanche, from the Predator series. But these examples are just the latest in a long line of Native creative work that has gained broader recognition over the past century, Cox says, and there are many writers and artists who built the foundation that led to this moment.

A cornerstone of that foundation, Cox says, is often traced back to the Native American Renaissance, a prolific period of Native American cultural and artistic production, spurred when Kiowa author N. Scott Momaday won the Pulitzer Prize in fiction in 1969 for his novel House Made of Dawn. The period that followed this book brought more Native writers to a broader reading audience and, along with the American Indian civil rights movement, opened a window for Native American visibility in politics, the arts, and more.

But Cox’s own scholarship reaches back further, to Rollie Lynn Riggs, a Cherokee playwright, author, and renaissance man who was active in the 1920s and ’30s, decades before the Native American Renaissance would formally begin.

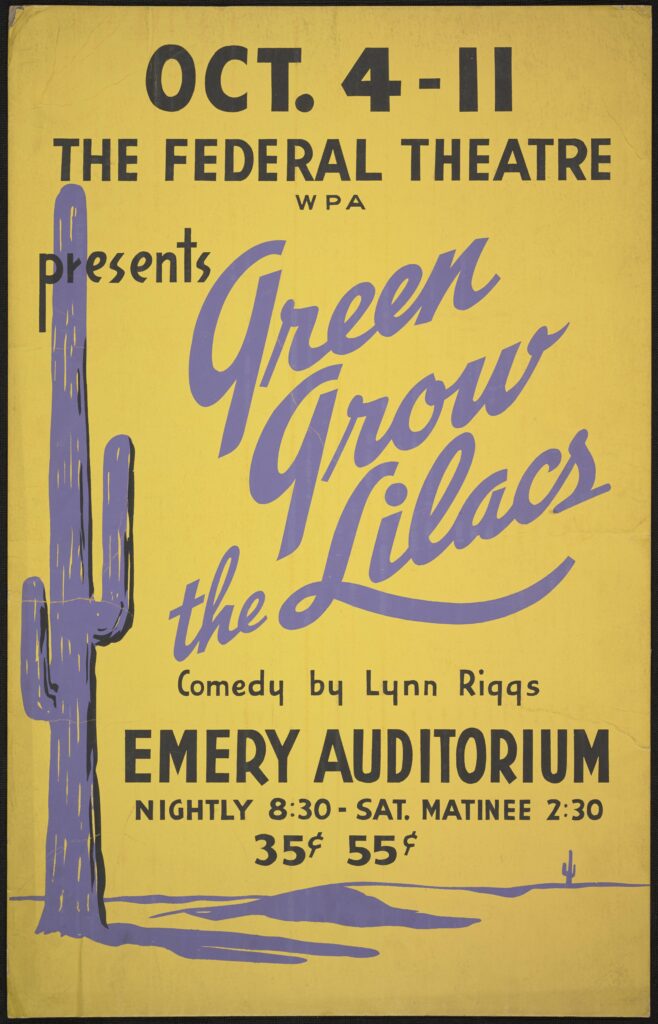

You probably don’t know that you already know Lynn Riggs. His 1931 Broadway play, Green Grow the Lilacs, was later adapted by Rodgers and Hammerstein into the smash-hit musical Oklahoma! — and that’s just one of the more than 20 plays he wrote, in addition to dozens of films, TV scripts, and poems.

Riggs was a prolific writer who spanned drama, poetry and more, and in many of his works he focused on Indigeneity and the experience of being a Native person in the Americas. He brought these themes to the public through his plays in particular, which Cox and co-editor Alexander Pettit collected in a new book from Broadview Press, Lynn Riggs: The Indigenous Plays (2024).

The conventional wisdom has been that Native writing before the Renaissance was too politically passive, Cox explains. At least one of Riggs’ plays, however, undermines that view. “One of his plays set in Mexico, The Year of Pilar, is, politically speaking, the most extraordinary piece of writing before the Native American Renaissance,” Cox says. The play is not only supportive of Native culture and communities, it’s also explicitly anti-colonial, which was highly unusual for its time.

“It’s a play that resonates still in 2024. People we introduce it to can’t believe it’s from the ‘30s,” Cox says.

Despite its significance, Riggs wasn’t famous for The Year of Pilar, or particularly famous in general despite his popularity. It’s not that he was unknown — he won a Guggenheim and had plays on Broadway and scripts in Hollywood — but there were bigger-name playwrights at the time, like Eugene O’Neill, Tennessee Williams, and Thornton Wilder, who held the spotlight. Riggs, by comparison, remained somewhat under the radar in terms of name recognition. And because Riggs produced so much, his work was sometimes perceived as unpredictable, full of shifts and experimentation, which left some audience members who expected one thing disappointed when they got another. As a consequence, he isn’t easy to teach in a survey course, especially one filled with other writers from his period, and so Riggs’ writing has gone undertaught and underappreciated.

But leaving Riggs out of the history of Native literature and U.S. drama is a mistake, Cox says. Because he was both so rooted in his Native American family and community and traveled and presented his work to such a broad audience, from local community theaters to Broadway, Riggs shared a genuine and rare window onto Native American life during his time. He presented the public with scenes that explored racial and class divides and the impact of federal legislation on Native American and Indigenous communities, and that dispelled stereotypes of Native Americans to broad, non-Native audiences.

By setting many of his plays in regional Indian Territory and writing in northeast Oklahoma dialect, for example, Riggs demonstrated that Native cultures of Northeastern Oklahoma, the Southwest, and Mexico were integral to the history of the U.S. in a way that other writers and dramatists weren’t yet doing — and he wove those threads into the canon of entertainment at the time across the United States.

“He had a real commitment to his regions’ [northeast Oklahoma] voices and he felt strongly about that,” says Cox.

Riggs’ experimental play The Cherokee Night, which premiered in 1932, features a young generation of Cherokees both before and after the establishment of Oklahoma statehood in 1907, an event that disintegrated tribal governments in Indian Territory and claimed lands that Indigenous communities didn’t gain back until the 1970s. The play begins with a group of young people of both Cherokee and white descent at a picnic, and slowly descends into betrayal and murder in a community impoverished by centuries of cultural oppression.

“That was a pretty bleak era in a long series of bleak eras, particularly for the Cherokees,” says Cox. “The play is grim and violent, but it’s a favorite of NAIS literary scholars because it’s so formally and politically extraordinary and a creative document about Cherokee life from the 1890s-1920s.”

Riggs’ 1936 play Russet Mantle, on the other hand, had a lighter tone. It satirized the affluent Anglo classes in Santa Fe and helped establish Riggs’s reputation as both a comic voice and an adept writer of dialogue. It proved his most popular production, premiering on Broadway and running for 117 performances.

This chronicling of local Native life, landscapes, and historical milestones is a feature of Riggs’ work that has also become a hallmark of Native writing in general, Cox says. And Riggs’ use of themes and historical references common to Native writing — such as the impact of federal legislation, the diminishment of tribal sovereignty, and the use of multiple voices and perspectives — helped to normalize their presence for broad audiences. This ensured that writers who came after him were able to connect with popular audiences and receive their due.

The theme of multiple narrators is a particularly important one, Cox says, as it emphasized the nature of Native communities as collective and collaborative. And while these were simultaneous voices in discrete pieces of writing, we might also look at the canon of Native literature as serving this purpose more broadly, with multiple narrators telling the story of Native people.

True to the importance of the collective voice, Cox explains, Riggs himself embodied this idea both within the content of his work and in his methods of working. He lived for collaboration and couldn’t have done his work at the level he did without it. Cox began to flesh out just how central the role of collaboration was for Riggs in a presentation for a conference for the 100th anniversary of the Native American Citizenship Act of 1924, which granted citizenship to all Native people. Cox revised this work for an article forthcoming in American Literary History.

“We were asked for the conference to think about citizenship, and I thought about the way Riggs lived his life and was an intensely loyal friend, and many of his friendships involved collaboration: José Limón, George Gershwin, Aaron Copland. People reached out to him to collaborate. So, I proposed that Riggs worked as ‘a citizen of the arts’ by supporting younger artists and friends and promoting them. It was a rare day he wasn’t reading his friends’ poems or songs. It’s why I think he’s such a fascinating figure. He knew what he loved and was devoted to it and wanted others to be devoted to it as well. Part of my argument as to why he chose theater/drama is because it’s inherently a collaborative art. He really preferred to work with people.”

As for the momentum of the current moment for Native literature, Cox hopes that it continues to bring more attention to Native people more generally. “It feels really good to have Native writers win awards and to have my colleagues outside of Native studies ask me about these books,” he says. “It’s all connected. The more writers you have, both creative and scholarly, spreading their ideas and talking with people, the more attention is on the many issues that Native people face.”