Jennifer Wilks began her newest book project with a seemingly simple question: “Why are there so many adaptations of Carmen set in African diasporic contexts?”

George Bizet’s 1875 Carmen, one of the most-performed operas of all time, is based on a far lesser-known 1845 novella of the same title by Prosper Mérimée. In neither of those 19th-century texts, however, does the lead character Carmen, by now a globally recognized archetype of an alluring and self-possessed woman living outside both the law and romantic conventions, have African ancestry. Instead, Mérimée and Bizet situate the character in Seville, Spain, among the Roma community, a group with a complex diasporic history of its own, tracing back to the Indian subcontinent.

How, then, did Carmen — a cigarette factory worker (and later outlaw smuggler) who embarks on a tragic affair with the dragoon corporal Don José, ultimately dying at his hands when he realizes he can never permanently possess her — become a Black icon?

Wilks’ new book, Carmen in Diaspora: Adaptation, Race, and Opera’s Most Famous Character (Oxford University Press, 2024), approaches that question through a series of deep dives into performance analysis and cultural history across France, Africa, the Caribbean, and the United States. Along the way, Carmen herself comes into focus as a historical character with a life of her own, appearing again and again across epochs and continents, enticing us and challenging us to measure the great changes in our notions of freedom and female power.

“I became interested in how performers were taking on this role and applying it to different cultural contexts,” Wilks says. “Also, how this role has played an important part in the careers of so many of the women who have performed her — for good and for bad.”

The subject first occurred to Wilks, now an associate professor at UT and director of the John L. Warfield Center for African and African American Studies, when she was living and teaching in France in 2006. At a Paris independent cinema, she caught a repertory screening of the South African film U-Carmen eKhayelitsha, which had won the Golden Bear — that is, top prize — at the 2005 Berlin Film Festival. Wilks was blown away by the depth of cultural exchange and reinterpretation on display in the film.

“It was such a stunning juxtaposition of contemporary South African culture, because it’s set there in the early 2000s, and 19th-century French culture, because it is sung through to Bizet’s score,” she explains. “And it just worked brilliantly.”

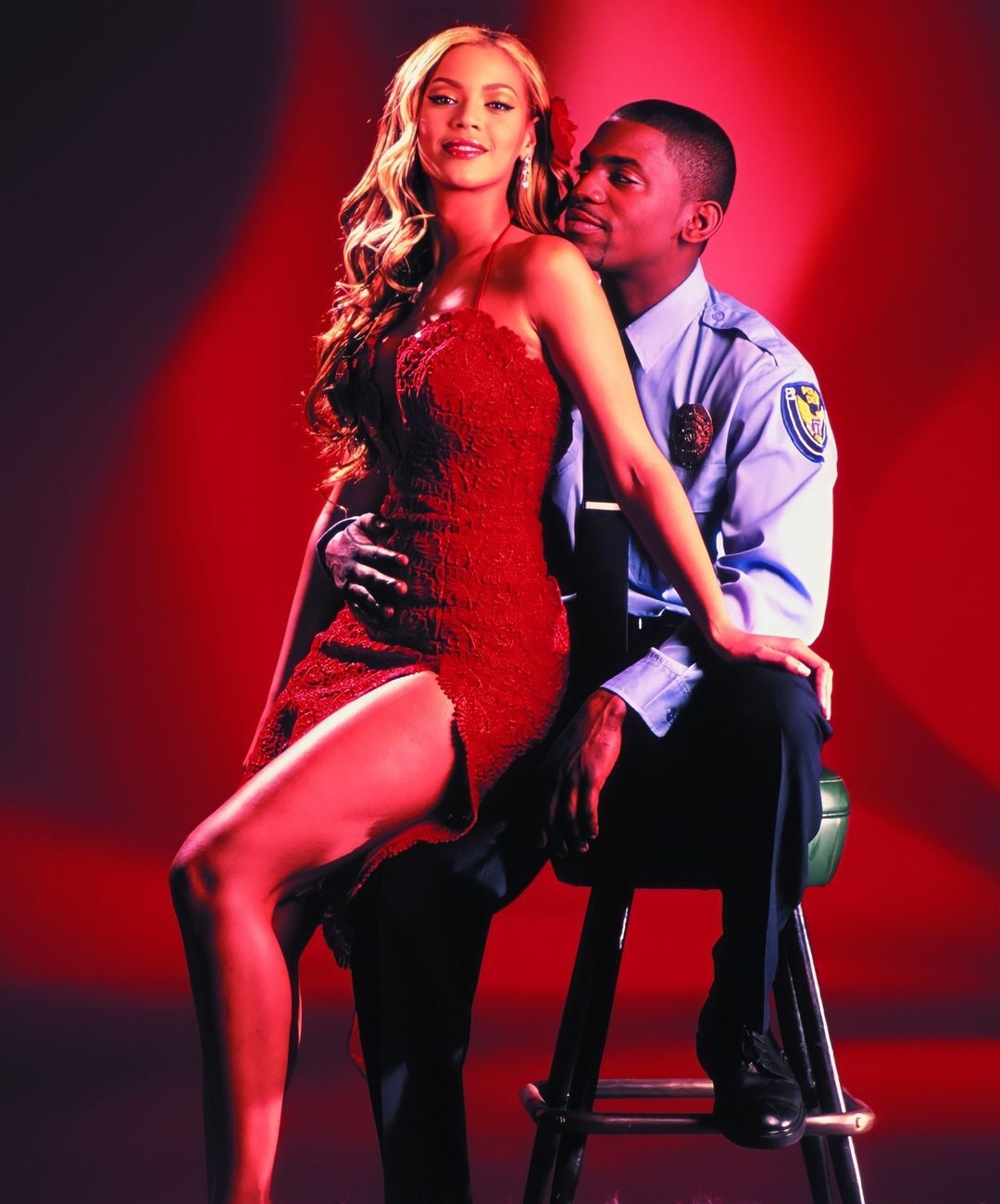

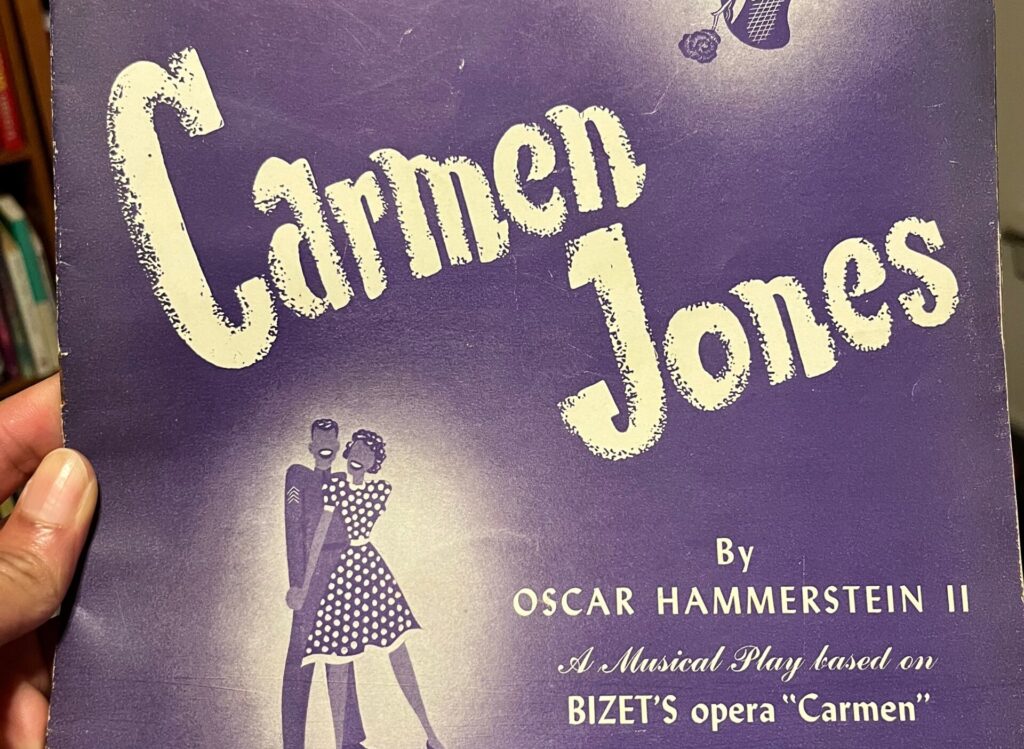

After the show, Wilks thought back to other adaptations of Carmen she’d seen. These included Carmen Jones, the 1954 film version of the Oscar Hammerstein II stage musical, which uses some of Bizet’s music and stars Dorothy Dandridge and Harry Belafonte. Another example that came to mind was Carmen: A Hip-Hopera, a 2001 TV movie starring a young Beyoncé Knowles, which aired on MTV to much fanfare about its first-of-its-kind blending of hip-hop and operatic musical tropes. Both films are set in Black milieus in the U.S.

Wilks found a key to understanding Carmen’s resonance in America in an introduction that Hammerstein wrote to the libretto of his stage musical in 1943.

“Hammerstein has this phrase, ‘The Gypsy is to Spain as the Negro is to the U.S.,’” Wilks says. “There are some problematic stereotypes that he leans into as he expounds on that idea, but what he is tapping into are very real similarities and resonances between the history of Roma populations in Europe, especially Spain, and African Americans in the U.S. and people of African descent more broadly.”

“They’re not shared histories, but they’re resonant histories,” Wilks says.

For instance, Wilks points out, Roma have had an uneven relationship to citizenship in Spain and elsewhere in Europe and have been subject to negative stereotypes. Also, Roma women are sometimes exoticized as a desired “other.” In the book, Wilks describes Carmen’s body as “one that tantalizes in its deviation from the presumably white standard and threatens because of its revelation of the fundamental instability of that standard.”

Here in America, the parallel but unequal careers of Dandridge and Beyoncé, an almost-A-lister of Golden Age Hollywood and the present-day genuine article, provide one of the most moving storylines of Wilks’s book. She includes a reproduction of Dandridge’s 1954 Life magazine cover — the first time a Black woman had ever been featured on the cover of that periodical, which was central in defining the values of postwar U.S. culture.

In this image, Dandridge stands angled away from the camera, glancing back enticingly over a bare shoulder. She wears a red flower in her black hair, a hoop earring and jangly bracelets, and places one hand on her back hip, as if mid-step in a flamenco. The cover text describes her as “fiery.” In the costume of Carmen, whose indominable charms eventually drive her jilted lover Don José to violence, Dandridge enters American living rooms as both an exotic flavor and a pathbreaking studio star in the making.

“To land a Life magazine cover for any performer was a huge deal in the mid-1950s,” Wilks says. “It means you are all-American, you are at the top of your game. And then for a Black woman performer to land a cover was even more significant. It symbolizes this moment of opening, of possibility. It means that Dorothy Dandridge as a performer has arrived, but it also points to broader strides that African American performers were making, in fits and starts, but in a significant way in the 1950s that they had not been able to make previously in the film industry.”

Carmen Jones earned Dandridge an Oscar nomination for Best Actress, another historic first for a Black woman. Yet for several reasons, including an explicit line in the Motion Picture Production Code (not removed until late 1956) forbidding interracial romance onscreen, her career never reached the heights envisaged by the Life cover. Dandridge died of a possible overdose 11 years later, performing in nightclubs to make ends meet.

As Wilks compares Dandridge’s career trajectory to that of Beyoncé a half-century later, a major shift is evident. The mononymous mega-star was beloved by fans of her girl group Destiny’s Child in 2001, but she was not a big enough name to even earn Carmen: A Hip-Hopera a theatrical release. Today, Beyoncé might be bigger than Carmen herself in terms of global recognition and legacy. Wilks attributes her success to both good historical timing and an ability to dictate the rules of her game in a way that Dandridge could not.

“I wouldn’t say that Beyoncé created a Carmen playbook for her career, but what she was able to do after the Hip-Hopera speaks to the agency and the ingenuity that the character of Carmen exhibits,” Wilks says. “It’s interesting to think about the breadth and depth of the career that she has gone on to have, and the ways in which the early 2000s was another moment of opportunity in U.S. pop culture, but one where the window stayed open. Whereas in the ‘50s, with Dandridge, because she wasn’t able to access that agency and flexibility, that window closed for her quickly after Carmen Jones.”

Much of the heft of Carmen in Diaspora is devoted to lesser-known adaptations of the source story. Wilks came to the topic as a scholar of Black modernism in the U.S. and Caribbean, and she begins her investigation with an analysis of “echoes of Carmen” in the novels of Wallace Thurman and Claude McKay, two writers associated with the Harlem Renaissance. This section underscores from the start the fact that it was Black creatives as much as those of European descent, like Hammerstein, who built the connection between Carmen and the African Diaspora. Wilks also devotes serious attention to Carmen la Cubana, a 2016 musical which readapts Carmen Jones’ story back to the stage and connects her to the story of the Cuban Revolution.

Wilks says the most fortuitous moment of her research was discovering Karmen Geï, a Senegalese film that first premiered at Cannes Film Festival in 2001. This adaptation finds a way to make the Carmen story sing in a fully Senegalese setting, using none of Bizet’s music; instead, the filmmakers employ a mix of traditional Senegalese music and American jazz. Wilks describes it as a sophisticated work that is the product of a post-colonial culture steeped in the French classics yet confidently speaking to a homegrown as well as international audience.

“It’s a testament to how people in Francophone societies that were colonies of France know French culture, but their work can be wholly Senegalese,” she says. “It is not a subordinate relationship to French culture. It is a peer relationship, and Senegalese culture is just as prominent. The richness of Senegalese culture is absolutely center-stage in that work. It’s probably my favorite adaptation.”

While Wilks sees many reasons to celebrate the role of Black creatives in claiming and transforming the legacy of Carmen, she does note with some disappointment a lack of female creative voices in the examples she’s found to write about. While the South African film U-Carmen eKhayelitsha credits female co-writers, most of the authors and directors she writes about are men.

“That’s important, because for so long Carmen has been known as this femme fatale,” Wilks says. “She’s the woman who lures men, in particular Don José, to their ruin, and she’s been reduced to that. That certainly brings dramatic tension to the work, but it’s a much more complicated story. The adaptations that I write about in the book, those directed by men, do lean into those complications in many ways, but I would just be curious to see how more women interpret this work.”

Wilks describes Carmen as, at its core, the story of a woman with boundaries, one who sings in her first and most famous “Habanera” aria, “If you love me, beware!”

Fortunately, woman-directed productions of Bizet’s Carmen — like the one at Austin Opera in May 2024, or the Metropolitan Opera’s New Year Eve 2023 production — are becoming more common, Wilks says. What remains is to see more women, particularly in the African diaspora, carry on the rich tradition of adaptation.

“Carmen has become an eternal, almost infinitely adaptable figure since the 19th century,” Wilks writes in her book’s introduction. We can only expect that entrusting her story to new generations of female storytellers and directors will reveal further, unexplored aspects of what Wilks calls her “unruly, powerful womanhood” to the world.