If classicist Andrew M. Riggsby had to give a speech about his dog Elmer — an extensive rousing one that he’d need to recall without effort or external aid — he would first visualize the strip mall near where he lives.

“I’d memorize all the stores, lock that layout down in my memory,” he explains. These are his loci. “Then I’d place an image of Elmer outside the first store; that’s where I tell the audience I’m going to speak about him. The second image, in front of the second store, might be of whipped cream, because there’s this great story of him jumping up on our dining table to get into a bowl. Then maybe an image of a tennis ball because he likes to play with us…” These are Riggsby’s imagines.

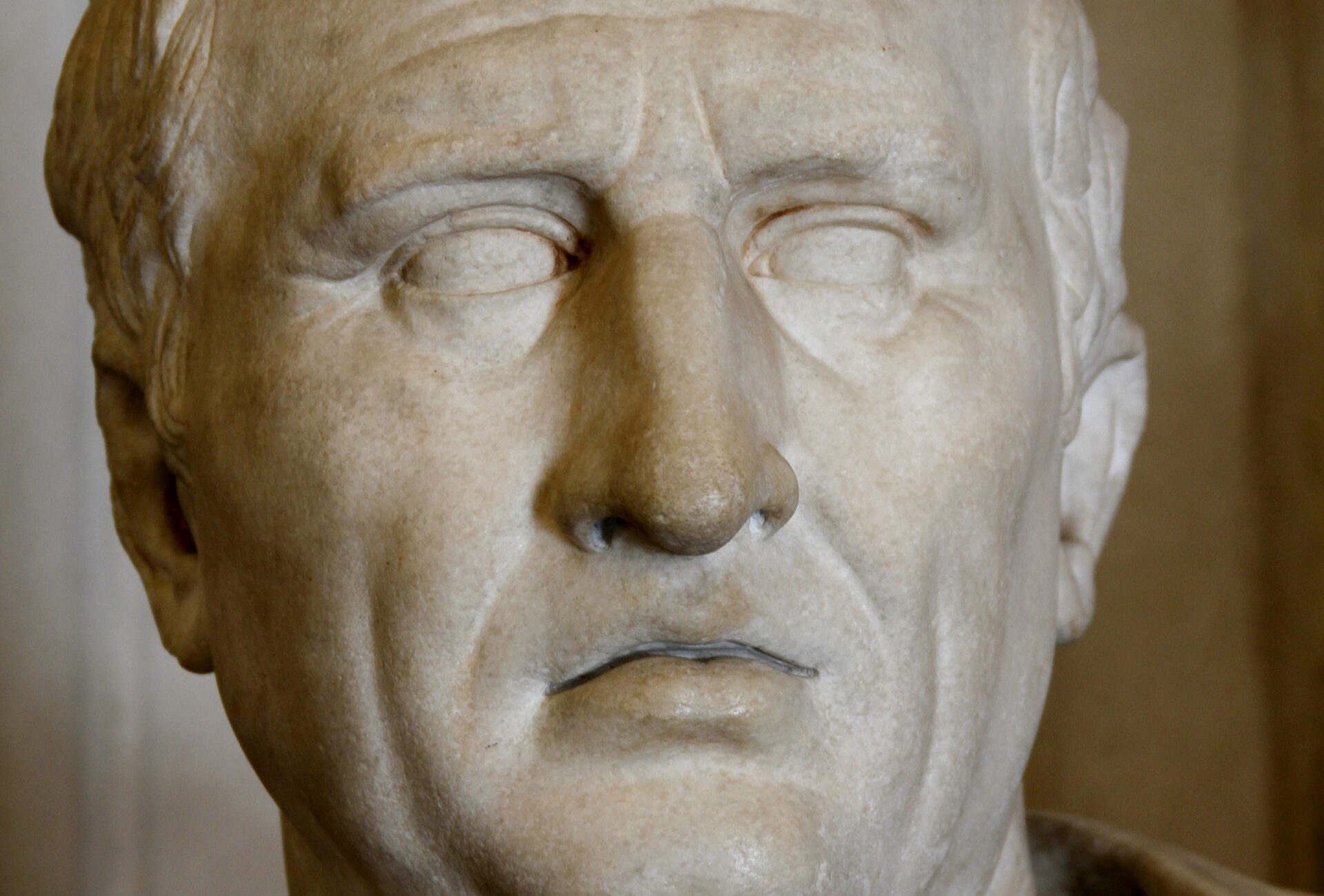

What Riggsby is describing is the loci method, a millenia-old mnemonic that can help you recall pieces of information (imagines) by mentally situating them in a location (locus) that you know well. It’s how orators like Cicero and Quinitilian were able to hold forth for hours on end in high-stakes settings — funerals, political assemblies — without veering off script. The technique is well-known. You might have come across a version of it without even realizing it, in the TV series Sherlock or the Booker Prize-winning novel Wolf Hall. Riggsby is describing it to me, however, to make a finer point. The method, he says, is strictly useful for recalling information in a precise order, not if you’re looking to improvise a little. It’s an argument he’s exploring in his current book project, Reading Roman Minds, an eclectic set of case studies that he describes as “an attempt to write the history of the ancient world with help from cognitive science.”

Like many men — a startling number, if a viral TikTok trend from last fall is to be believed —Riggsby thinks often and at length about ancient Rome. Unlike most men, however, the Lucy Shoe Meritt Professor in Classics (and professor of art history) has devoted his life to its study. Rather than togas and aqueducts and gladiatorial battles, Riggsby mostly thinks about how ancient Romans thought. Along with the loftier aspects of classical knowledge, such as rhetoric or philosophy or literature or antiquity’s other formalized disciplines, he also studies the more mundane: lists, tables, weights and measures, maps, and political advice letters. Riggsby, simply put, is interested in the different ways in which ancient Romans processed information on the page — or on walls or wax tablets — and in their heads.

Riggsby hasn’t yet delivered a lecture using the loci method, but “I really should, just for the practice,” he says, chuckling. “In class, I’m usually projecting an outline so my students can see it.” He pauses, before adding, “But it’s remarkable to read the technical literature where people are introduced to this technique and 30 minutes later it has a measurable impact on their ability to memorize things in order.”

When Riggsby began work in this area a decade and a half ago, he spent a year as a fellow at the American Academy in Rome. “Conversations there always began with, ‘What are you working on?’” he recalls. “And I found myself saying over and over, ‘Well it’s this and also this.’ One part was about how ancient Romans deliberately organized information, usually in writing, that could be studied in sort of a technological way. And the other part was about how their brain was doing the organizing for them.” These projects, he realized, were separate ones. He set to work tackling them one by one, in that order.

The first line of inquiry culminated in Mosaics of Knowledge: Representing Information in the Roman World (Oxford University Press, 2019), a book that casts a fresh look through the lens of the history of technology at inscriptions, artworks, and other small artifacts originating in the Latin-speaking world between 200 BC and 300 AD. Riggsby studied how and when Roman administrators used an index or a table of contents, for instance, or how muralists conceptualized space in landscape paintings.

Reading Roman Minds is the second part of his now bifurcated project, currently in progress with the help of a fellowship from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation. The book is being built around a set of specific examples from the ancient Roman world, which Riggsby considers in conjunction with modern scientific findings. The loci method is one of them, which he examines as a plausible solution to the cognitive challenge of “serial memory.” The production of Roman jurisprudence is another, which Riggsby considers through the contemporary framework of “distributed cognition.” First articulated in 1995, this theory proposes that thinking doesn’t just take place within the brain of a single person but can extend over time, space, objects, and other people. An often-invoked example of distributed cognition is the navigation of ships before the advent of satellite systems, which involved many sailors above and below deck working together to decide how to steer the vessel. Ancient Roman jurists and their writings, Riggsby argues, produced answers to legal questions in a similar manner.

A different example considers the many words in Latin to describe fear, which Riggsby is examining through the lens of modern linguistics, amid ongoing debates over whether the words all mean exactly the same thing. Another explores seemingly odd motifs in Roman wall paintings. The diverse assortment of cases is unified by the classicist’s overarching interest in “how modern science can both resolve old questions and open up new lines of inquiry,” as well as what history can offer back to cognitive studies.

Riggsby credits much of his interest in crossing back and forth over the seemingly daunting divide between the humanities and the sciences to his background. It was just in the water growing up. His great-grandfather and grandfather were both psychology professors. His father was a scientist and his mother had science degrees. Once he decided to become a professor — “I didn’t even really decide that; it just never occurred to me to do anything else”— he considered math but ultimately opted for classics. As a graduate student at UC Berkeley, his department was housed in the same building as linguistics. “They were really into all this cognitive stuff. It’s where George Lakoff taught,” he recalls. “And so, just by hanging out with those students, I was picking up a certain amount of that.”

Riggsby, who is nearly 60 now, is finding it easier than ever to think flexibly and work experimentally. “I think this sort of work would be very hard to do if you were 30; you just wouldn’t have enough time to acquire this kind of knowledge in a lot of different places,” he reflects. He often ends up writing two versions of the same paper, one aimed at classicists, one at cognitive scientists. A recent publication in a cognitive science journal, “What Kind of Cognitive Technology is a ‘Memory House’?” will appear, slightly modified, in his forthcoming book aimed at classicists.

“You can get a fair amount done by a fairly narrow case study structure. I know a lot about serial memory now,” he says.

Along the way, he’s learned to be adventurous in a way that is unusual for a classicist. “When should you take a chance and say, ‘the best current thinking is this and I’m going to go with it?’” he muses. “The scientists live with it, right? They publish papers they know could actually be refuted. If we’re going to move in these directions, maybe we have to be just a little more tolerant of the possibility that something better will come up later.”

Riggsby hopes other historians will move in this direction, despite all its attendant challenges, and that Reading Roman Minds will serve as introduction, encouragement, and guide when they do so. “My real hope here is not so much that I will then do a sequel but to get other people to jump on the bandwagon,” he says. “Whether you work on France in the 1700s or the Congo in the 12th century, many of the questions are the same.”