You probably know the signs of hoarding: detritus in the yard or driveway, curtains or blinds pushed up against the windows. You may even have a hoarder in your family. But according to assistant professor of Italian studies Rebecca Falkoff, what you don’t know about hoarding is, well, a lot of stuff.

The fifth edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5) included hoarding disorder for the first time in 2013, defining it as “persistent difficulty discarding or parting with possessions, regardless of their actual value,” that “causes clinically significant distress or impairment.” While this definition isn’t wrong, says Falkoff, it was coined for a specific purpose: diagnosis by a clinician, ideally with the aim of getting care for the person with the disorder. For her, hoarding requires a different kind of definition, and she argues that it is symptomatic of much more than just an individual disorder. Falkoff — who literally wrote the book on hoarding, 2021’s Possessed: A Cultural History of Hoarding (Cornell University Press) — instead describes hoarding as “a cultural discourse produced by clash in perspectives about the meaning and value of objects.”

“Hoarding produces real difficulties in life,” she says, “and in order for people to access resources that can help them, there needs to be a diagnostic code. But a pile of objects is not a hoard unless you have one idea that it is and one that it’s not. Those ideas can coexist in the same person, among different people, at different moments in time, or in different cultural or political contexts.”

An object you love might seem precious in isolation, but less so when it crowds your space or when you feel ashamed when someone comes to the door: that’s an example of two perspectives in one person, Falkoff says. Time can create this clash too, such as when the excitement of acquiring an object later turns into despair about its presence.

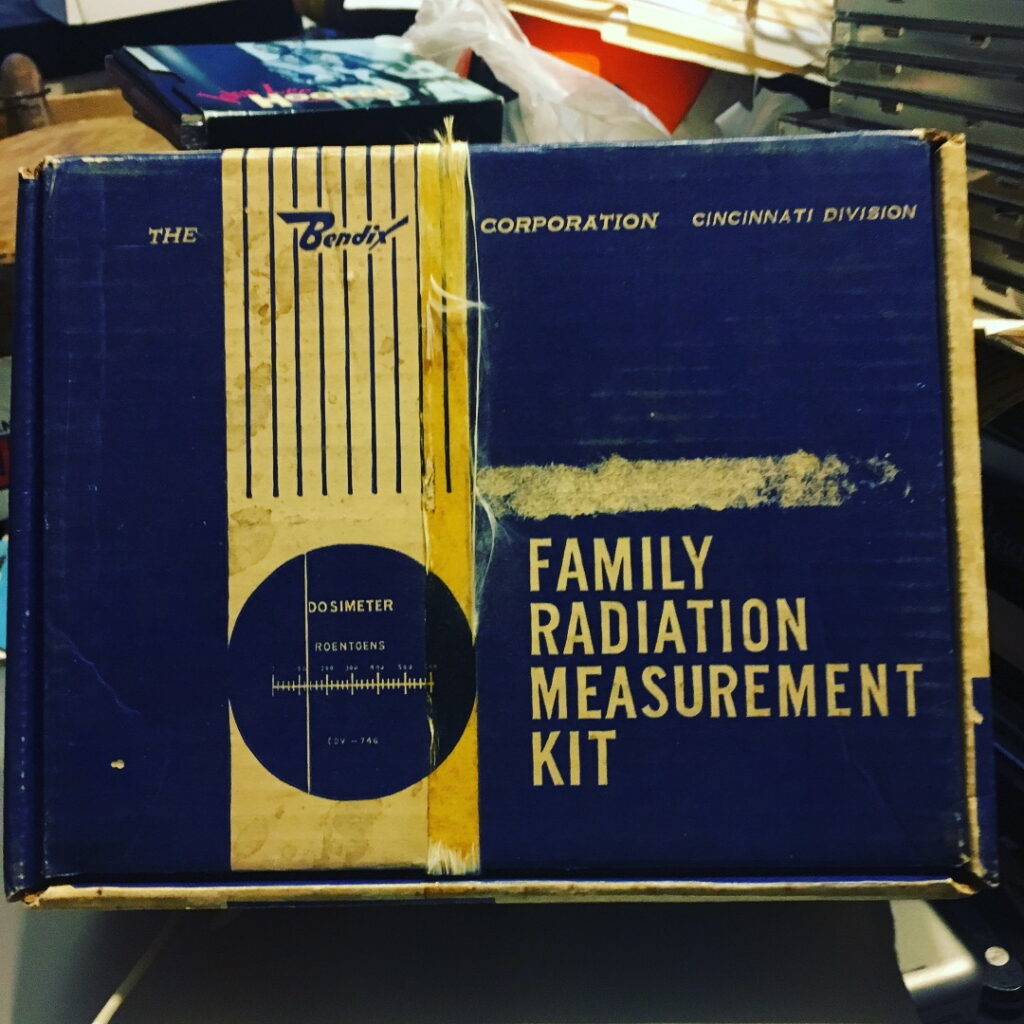

But in certain cultural and political environments, there can be a real logic to hoarding rooted in the idea of not being wasteful or of stockpiling during hard times. In Eastern Bloc countries under Soviet rule, for example, the political regime promoted propaganda about abundance while people were actually experiencing scarcity. In that context, an isolated world where self-sufficiency was a necessity for survival, hoarding made good sense.

Hoarding can also be a rational response to the value of goods changing over time, or an effort to accumulate enough of something to control the market in a way that makes it more valuable. “It’s kind of the epitome of what makes for good speculation on the part of the investor,” Falkoff explains. In a way, our modern societies highly value this type of economic forethought or “futures” speculating (think, “now is the time to buy gold!”).

Falkoff also sees the hoarder as representing a failure of some of the most celebrated figures of modernity — not only the investor or speculator but also the artist, poet, or collector.

“Consider [the artist Marcel] Duchamp, whose readymade works like Fountain (a porcelain urinal, presented as a sculpture), transform something worthless into something priceless,” she says. “A yard scattered with junk — like an old toilet, a couple bathtubs, a sink and a dishwasher — might look like hoarding, but works like Fountain remind us that the mystery of value is more complicated. A hoarder may find beauty or meaning where others see none, but if a hoarder can convince others of the value they see, they start to seem more like an artist, poet, or collector.”

Intellectual perspectives aside, tough questions about the very real dangers hoarding can pose for people with the disorder and how society treats them persist. For Falkoff, these questions get personal. Recently, she and some family members spent nearly two years cleaning out her father’s house.

“It was an enormous project that was very different from the more abstract work of my book,” she says, “It was sometimes devastating to be in that space — it was a testament to so much isolation and sorrow.”

But you don’t need to personally know and love a hoarder to be concerned about those living with the disorder and how they’re commonly depicted. Consider the TV show, Hoarders (2009-) (and the fact that hoarding has become the subject of a TV show at all). The first episode features a woman of retirement age recently diagnosed with cancer. Her landlord is threatening to evict her because of her hoarding — mainly expired food, and, most vividly, a couple of rotting pumpkins. But is her hoarding really her most serious challenge?

“We should probably be more concerned about the other problems she faces,” says Falkoff. “We could focus on the need for affordable health care and housing. Who cares about a rotting pumpkin?”

Her point is that treating hoarding as a personal failure or a spectacle obscures society’s responsibility to solve some of the issues that can lead to hoarding, like scarcity for some or the loss of meaning to history. If you consider the logic of a hoard, there’s nothing fundamentally wrong with wanting to preserve things, or with the impulse or commitment to document history. It’s just that we just don’t often support the frameworks necessary for doing so, and that can lead to people living in spaces that become dangerous, where chance encounters overwhelm the initial intention.

After all, a hoard in someone’s home is rarely just junk, and isn’t it just someone’s opinion, or a boarder cultural consensus, that determines what is junk and what isn’t? As Falkoff points out, part of the DSM-5 definition of hoarding is an inability to discard things regardless of their actual value. “But value is not inherent in any given thing,” she says.

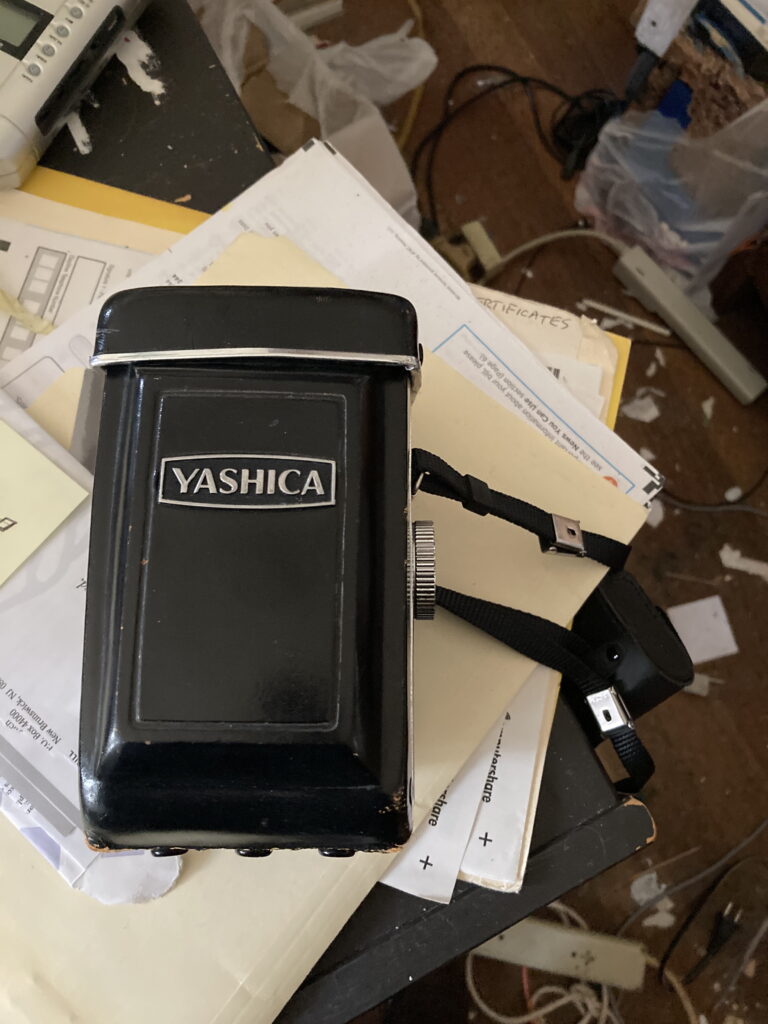

As she and her family were going through the long and difficult process of cleaning out her dad’s home, Falkoff also felt excited about some of the things they uncovered. “There was so much to learn from all these strange objects — tools and machinery, cowboy boots, antiquities, musical instruments, coffeemakers, and clunky old film and audio-recording devices,” she says. “Every time I went there, I found something cool that I had never seen before. It’s a kind of experiential learning I would wish everyone could experience, if it weren’t so dangerous and sad.”

But what does all this have to do with Italian studies, Falkoff’s area of scholarship? While her interests in both literature and hoarding might at first seem disparate — or even in themselves a little bit like a hoard — it turns out there are strong connections between the two that allow us to see both literature and hoarding in new ways.

When Falkoff started reading Italian literature in college, she began noticing patterns in the work of the authors she loved, particularly that of Carlo Emilio Gadda (1893-1973). There was something about his literary style and themes that evoked hoarding. “Reading Gadda, noticing the talk of hoarding everywhere around me, and dealing with the hoarding in my family,” she says, “I realized I had a lot to add to the conversation.”

Gadda was a modernist writer, known by some as the Italian James Joyce. His work features complex language often described as “plurilingual,” blending high and low registers and mixing in French, German, Greek, Latin, Spanish, and various Italian regional dialects. He also made up new words. His lexicon is so unusual that scholar Paola Italia created a “Gaddabolario,” a dictionary of Gadda’s words.

“There’s a structural resemblance to hoarding in Gadda’s writing,” explains Falkoff. “His use of digressions often suggests a kind of privileging of chance over intentionality. It’s as though he gets sidetracked by a passing thought. The pastiche of registers and languages, the digressive plots, and the inclusion of arcane trivia and technical knowledge brings a sometimes-overwhelming heterogeneity to his work.” Sound familiar?

Gadda was also interested in hoarding itself and wrote a short story titled “L’Adalgisa” about a woman whose late husband thought of himself as an entomologist, minerologist, philatelist, numismatist, and paleontologist. Their house is inundated with insect, rock, stamp, coin, and fossil specimens that she discovers are worthless.

Gadda was was also something of a hoarder himself: “He has described himself as an archiviomane, or an archivomaniac,” says Falkoff, “because he never threw anything out. His own material legacy poses tough questions for archivists on whether to preserve the ephemera he accumulated. Just thinking about and working on Gadda poses a lot of questions about hoarding.”

Falkoff’s also sees elements of hoarding’s psychology in other Italian works, such as that of literary superstar Elena Ferrante. There’s a passage in the author’s first novel, L’amore molesto, or Troubling Love, where a character returns to her mother’s home after her death and sees the faucet dripping. The narrator thinks that her mother, who would never have let the faucet drip, must have wasted more water since her death than she did during her life. Falkoff recognizes in this scene the same kind of moral aversion to wasting that appears in many iterations of hoarding.

Even Falkoff’s new book-in-progress on atmospheric nitrogen capture, Modernity in the Air, connects to hoarding. The project grew from her love of Gadda, who worked as an engineer in the 1920s and ‘30s at a company that produced synthetic ammonia from atmospheric nitrogen. During that time, he wrote a series of articles about the industrial technology they were using.

“The essays are so erudite and poetic, that they brought into focus the ideological power of the technologies,” Falkoff explains. “I realized through Gadda’s work how essential technology was to the ways that fascist strategy developed.” With his writing as her guide, Falkoff recognized changing social and economic relationships between scarcity and abundance, materiality and immateriality. “Hoarding is about an abundance of tangible materials charged with powerful fantasies, while nitrogen capture is about using something that seems immaterial — the air — to make materials like fertilizer and explosives,” she says.

We create hoards in more ways than we realize — both as individuals and as societies — and Falkoff wants us to understand that each method of doing so can tell us something about who we are and where we come from. This both explains why her own approach to the topic can feel so eclectic and why she thinks everyone can benefit from considering hoarding more deeply. “Every discipline has a way of thinking about something that’s like hoarding,” she says, because, “to some extent, it’s a question of the broader cultural consensus about value.”