Do we sell a liberal arts education as preparation for the professional world, or as a chance to explore the deepest questions of human existence? This is the x or y question that haunts my professional existence. One of my least favorite answers, usually, is “x and y. It’s both.” Yeah, right. It’s an evasion of the hard choice, with the result that neither narrative gets its due.

It was a nice surprise, then, when associate professor of sociology Jordan Conwell persuaded me that we really could have both. I’d reached out to him because his department chair, Shannon Cavanagh, had sent me a link to some materials about a project that Conwell is coordinating with our college’s Liberal Arts Career Services team. This project, the Sociology Pathways and Career Engagement Resource, or SPACER, is an online curriculum that can be incorporated into a standard sociology course. It’s made up of 15 modules, one for each week of a semester-long course, that cover topics like transferable skills, “marketing your degree,” resumes, interviewing, social media, and creating a “career game plan.” A National Science Foundation award to Conwell, set to run through 2029, is funding the work.

Conwell piloted the curriculum in his spring 2025 section of “Social Research Methods,” a required course for sociology majors that enrolls sophomores, juniors, and seniors, and the department is planning to expand it to other courses as well. The hope is that SPACER will not just prepare students for careers but will inform their course, certificate, and extracurricular decisions so that they align with students’ long-term goals; familiarize students with where to find expert career help on campus; and pre-empt the fears that keep many students from joining or staying in the major in the first place. It’s a program, but also a sales pitch for the major.

At first glance, SPACER appears to be very much on the pragmatic side of the binary that I’m always worrying over when it comes to pitching the liberal arts to the world. It’s about the job, the brand, the resume, the interview, and the game plan rather than the Truth and the search for knowledge and wisdom for their own sake. Talking to Conwell was gratifying, though, precisely because he doesn’t see the two narratives as being opposed. Instead, he sees the program as a way of helping students to accomplish two complementary goals: They’ll better articulate to themselves what values they want to bring to the world while also making a plan for concretely realizing those values in the work they do.

“A small number of our students will go on to get their Ph.D.s in sociology or a related field, as I did, and get university teaching jobs,” says Conwell, who arrived at UT Austin in 2021, “and that’s great. But the reality is that most of them won’t. They’ll become K-12 teachers, lawyers, social workers, doctors, tech executives, clergy. What we want them thinking about, from the beginning, is how what they’re learning in our program can lead them to a life of purpose and meaning. That exploration shouldn’t be separate from thinking about the job they’ll do to earn a living, and the two can be mutually reinforcing.”

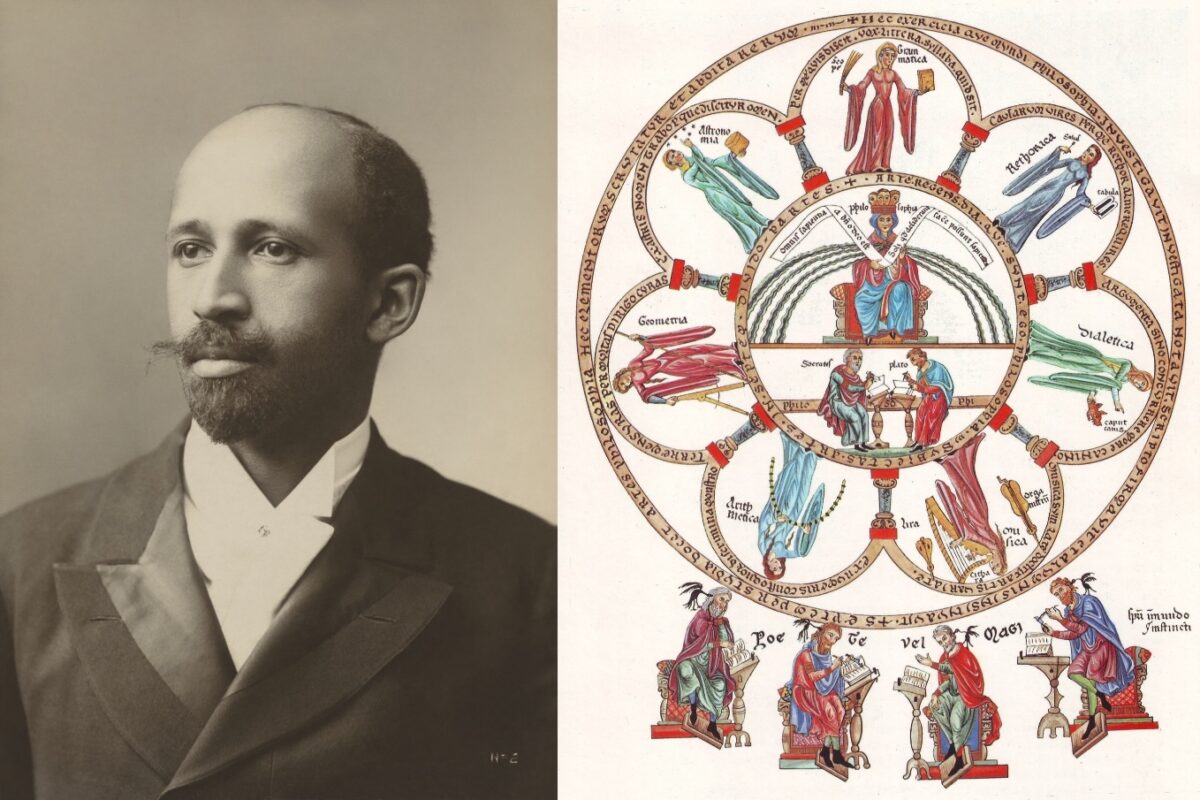

One of Conwell’s theoretical touchstones in thinking about the future of higher education is W.E.B. Du Bois’s classic essay, “Education and Work,” which Du Bois first presented as Howard University’s commencement speaker in 1930. The speech was a return to Du Bois’s famous debate with Booker T. Washington over how Black men and women should be educated in the United States in the aftermath of emancipation but in the face of continued discrimination and segregation. Should technical and professional skills be prioritized, as Washington believed, so that students would be optimally prepared to attain material success (and therefore be better positioned to attain political power as well)? Or would too much of a focus on the pre-professional, and too little focus on the underlying nature of the society, simply prepare them to continue to be exploited by a rigged system, albeit at a higher income level?

Du Bois’s answer, in 1930, was both x and y. “We need then, first, training as human beings in general knowledge and experience,” he wrote, “and then technical training to guide and do a specific part of the world’s work.” Students need to understand the world in order to form and sustain a vision of how they want to shape it, and they need the pragmatic skills and knowledge to realize such a vision.

SPACER, for Conwell, is a Du Boisian endeavor. It’s not an evasion of the tension between the practical and idealist ends of a liberal arts education but rather is an effort to breach what is too often a firewall between what students are learning in their classes and what they’ll go on to do professionally after graduation. Conwell sees embracing that tension, as opposed to running from it, as critical at the current moment in higher education. “Now more than ever, we should be clearly articulating the multiple dimensions of value that sociology and other liberal arts degree programs offer our students, their families, and their communities,” he says.

For me, as a salesman, a nice side benefit of this way at looking at the liberal arts is that it points to certain language and concepts we might be able to deploy in our recruitment efforts that would tap into some of the deepest symbolic currents in American culture and history. I’m thinking of words like “vocation” and “calling” and “purpose,” and of symbols and stories drawn from ancient religious and wisdom traditions that see our labor as one of the primary vehicles for realizing our spiritual ideals in the world.

It would be challenging, of course, to take these heavy-duty ideas and symbols and translate them into… well, a sales pitch. But that’s precisely the kind of challenge that the field of university communications has evolved to confront, and one that has its own Du Boisian spirit. It’s a pragmatic task, with a material goal in mind, but it’s informed at the deepest level by humanistic education and humanistic objectives.