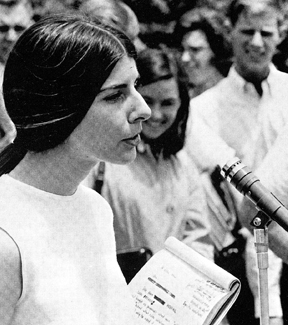

Alice Embree doesn’t know what came over her the first time she stood up against injustice. She just knew it was the right thing to do.

Along with her friends Karen and Glodine and the rest of the Austin High School drill squad, Embree had just sat down to order at a restaurant in Corpus Christi when a waitress approached Glodine, the sole African American on the squad, and said, “Honey, we just can’t serve you here.”

“They won’t serve Glodine. We need to leave,” Embree recalls saying almost instinctively to her teammates, but they wouldn’t budge, muttering the excuse, “but we just ordered.”

“It was as if the decorum of the place was more important than the principle to everybody else,” Embree says.

She and her two friends were the only ones who left to eat lunch at Woolworth’s, which was integrated at the time, before meeting back up with the rest of the group. That moment, she says, foreshadowed becoming a freshman at The University of Texas at Austin in 1963 when its dormitories and sports teams were still segregated and in a city that was still enforcing poll taxes.

“We’d been raised to believe certain things about the country and suddenly they appeared not to be true at all, like ‘we’re all created equal,’” scoffs Embree, who came to UT to study anthropology, though she admits her major might as well have been “SDS” — Students for a Democratic Society, a 1960s student activist group of the New Left.

By the mid-1960s, the pressures of the draft for the Vietnam War and disparities between race and gender populations were becoming intolerable. There was an outcry for peace, demands for true equality, and an uproar of women defying gender norms in the name of liberation.

“That was the environment that changed me into an activist,” Embree says.

Raised Voices, and Suspicions

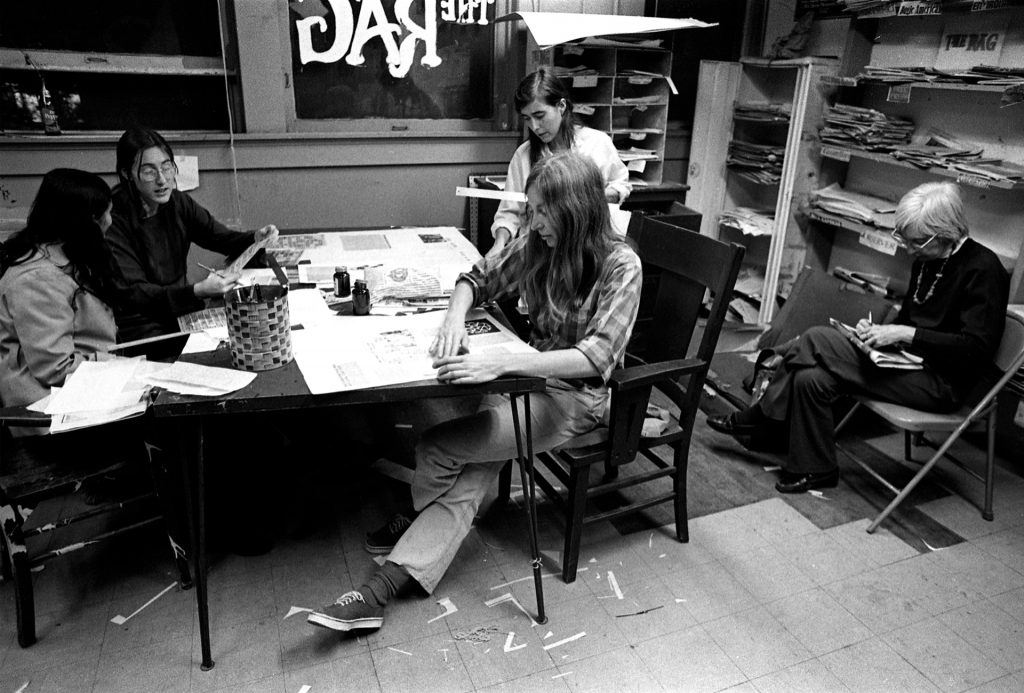

Embree became involved with SDS after she was handed a copy of the Port Huron Statement —the group’s manifesto — while walking through UT’s West Mall. From there she began working on an underground, counterculture newspaper called The Rag, which was founded in 1966, first as a typist and later as a writer. It was a time when women in the office pushed to have their voices heard.

“The Rag really embraced women’s liberation while a lot of other underground newspapers literally imploded,” says Embree. In each week’s issue, The Rag shared viewpoints on the black struggle, the farm workers’ movement, women’s liberation, free speech, anti-war protests and other social grievances that the local and national papers weren’t reporting.

“We wanted to have an alternative view to the media,” says UT law professor Barbara Hines, who came to UT in 1965 to study Spanish and Latin American studies while also getting involved with The Rag and women’s movement. “Remember, this is a time way before the internet. There were limited viewpoints you could access in the media.”

Despite the university’s attempt to stifle their editorial voices and printers around town refusing to print material with such crude language and radical viewpoints, The Rag pressed on.

Cries for liberation spread like wildfire at UT and across the U.S. as women came together in consciousness-raising groups to discuss their experiences.

“I guess you have to understand that women didn’t do that before, that that was such a novel approach,” Embree says, adding that against the backdrop of the civil rights, free speech and anti-war movements, women began to understand their story as a social structure.

“You’re in a framework that’s like a prison under patriarchy. Whether you like it or not, you have all these barriers and all these things and expectations that encircle you,” says Martha Cotera, who participated in the Chicano and women’s liberation movements. “The patriarchy has control over our reproductive lives, control over economic lives, control over our thinking and cultural lives, control over everything to keep the cage in place.”

These women looked at a variety of issues, building off of questions asked in the civil rights struggle and the war struggle, and they began to consider and challenge the age-old expectations of wifehood and motherhood and push for autonomy as sexual beings, Embree says. They examined employment barriers and pay scales, realizing the concept of “the glass ceiling” before it even had a name.

“It was eye-opening for all of us because I think it was the first time that women really talked about the socialization and the objectification of women and the discrimination against women,” Hines says.

Off campus, there were no female firefighters, police officers, or EMS workers. And if a woman tried to enter one of those professions, it was either through a lawsuit or a threat of a lawsuit, Embree explains. By 1968, women made up only 7 percent of doctors, 3 percent of lawyers and 1 percent of engineers and were making 40 percent less than men for the same jobs nationwide. And campus was a reflection of that. There were few female graduate students and even fewer female faculty members.

“To go to law school or medical school was to make a political statement,” says Hines. She was classified as “Disloyal No. 3, known to sympathize with members of the Communist Party” in a 100-page FBI file detailing her involvement in the women’s liberation movement — though Hines says she was never involved with the Communist Party.

It seems there had been a mole attending The Rag and women’s liberation meetings. “Source stated that women’s liberation is basically opposed to male chauvinism to the point of eliminating the wearing of brassieres and clean attire in order not to be a sex symbol,” the FBI file continues. “The group also favors abortion.”

Getting Organized

It was a time of mass domestic surveillance in the U.S. under FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover, who trained the agency’s eyes and ears on anyone suspected of posing a political threat.

Some fears circulated around the possibility of a phone tap at the Y, where Hines and other women ran a birth control counseling center in a small room next to The Rag’s office. At the time, birth control was not available to anyone who wasn’t married or engaged — or had some form of acne that could only be cleared with the pill’s high dosage of progesterone, Hines adds, offering one way women were able to get around the restriction.

Their operation seemed low risk enough to advertise in The Rag, but eventually women started asking questions about abortions.

“We sent women who had money to other states where it was legal, but primarily we sent women to a doctor in Eagle Pass — well, he was actually in Piedras Negras, just south of the border,” says Hines, who is also affiliated with the UT Austin Immigration Studies Initiative.

The group became concerned with their liability under conspiracy laws as aiders and abettors and reached out to one of the only lawyers they thought would be willing to help: Sarah Weddington, who recounts in her book, A Question of Choice, the conversation she had with the student group that sparked her decision to take on the case of Roe v. Wade.

“If you think back to 1970, there was not a woman gynecologist in Travis County. You couldn’t get birth control prescriptions unless you were married, except for one doctor. Women had no resources whatsoever to help them control reproduction. All of these things kind of kindled change,” Embree says. “We brought attention to that, and then we began to make changes.”

“Source stated that women’s liberation is basically opposed to male chauvinism to the point of eliminating the wearing of brassieres and clean attire in order not to be a sex symbol.” (From a 100-page FBI file detailing Barbara Hines’s involvement in the women’s liberation movement)

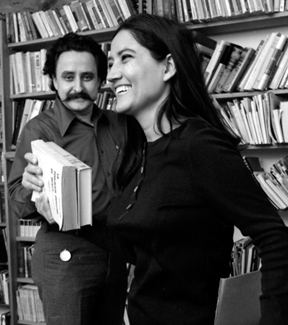

Austin women activists began to call foul on issues related to domestic and sexual violence. In working with the Mexican American Business and Professional Women — “a safe name that hid radical work” — Cotera helped open the Austin Rape Crisis Center in 1974 and the Center for Battered Women in 1977.

“We did a lot in bringing the churches around, and the police and the courts around to negotiate services for rape victims and victims of domestic abuse,” says Cotera, who learned about the terrors of domestic abuse when living in Crystal City, Texas, and working with teachers who were sheltering women and children who suffered domestic abuse.

“I learned how risky it is to host abused families in a house with the potential of angry spouses locating them and endangering everyone in the house, including the host,” Cotera says. “That’s when we arrived at the idea that you needed to have a neutral territory that was well-secured to keep people safe.”

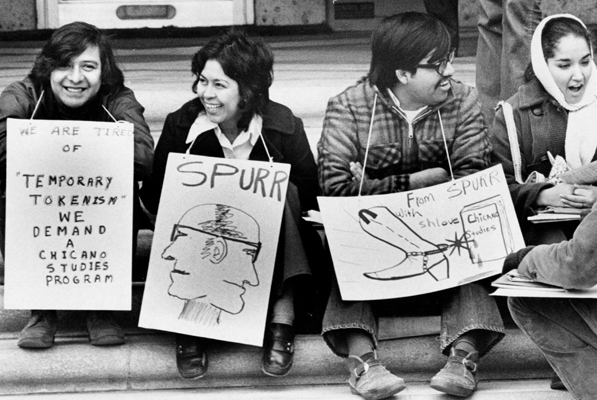

On campus, Cotera focused her efforts on organizing ethnic studies education and establishing the university’s Center for Mexican American Studies.

“Things weren’t happening fast enough, so we took off with other educational activists to start our own independent college,” says Cotera, describing the idea that led to establishing Jacinto Trevino College in Mercedes, Texas, in 1969. “It was a way to do it quickly, to educate more teachers.”

Though she laughs and admits the whole idea sounds crazy now, she knew the importance cultural institutions would have in providing a real, holistic education to students, so much so that she also helped establish Austin’s Mexican American Cultural Center and ardently supported the Mexic-Arte Museum within the same decade.

“When you’re at the bottom, every little gain that you make, you’re happy for,” Cotera says. “I thought our movement might last forever and go on and on and on.”

Untold History

“It’s amazing to me how important this history is here that isn’t told,” says Laurie Green, a UT Austin history and women’s and gender studies professor who argues that most of the narratives about the women’s liberation movement focus on the Northeast, the Midwest or the West Coast, not the South and certainly not Austin, Texas.

This omission sparked the idea for her fall 2017 class assignment — a women’s activism memoir project in which Green’s students would interview women’s liberation activists who had either attended UT or lived in Austin in the ’60s and ’70s, including Cotera, Embree and Hines.

“I wanted this history to be real for them and understand that this is their history — this is our history,” Green asserts.

To ensure these women’s stories wouldn’t vanish from history as many often do, Green partnered with the university’s Dolph Briscoe Center for American History to archive the transcripts and recorded interviews between the students and activists in a permanent collection that will soon be accessible for others to study for years to come.

“Women’s history is a very rich and lively kind of study, especially when we really reach deep into the lives of these activists who define activism in a very broad way,” says Jacqueline Jones, professor of history at UT and chair of the department. “Yet, a lot of that has been lost to us. That’s why this project is so important.”

Watch “Fight Like A Girl,” a mini documentary on what UT students learned about Austin’s Women’s Liberation Movement:

Oftentimes, women’s activity of the past is painted with a very broad brush, garnering titles such as “first wave” or “second wave”— both of which were described for the first time in a 1968 New York Times article, “The Second Feminist Wave,” which outlined the demands of the National Organization for Women (NOW).

Classifying these eras as “waves” can be problematic because they compress all women activists and all their struggles from the mid-19th century to the late-20th century into just two compartments: the women’s suffrage movement, which ended in 1920 with the 19th Amendment, and women’s activism of the 1960s and 1970s.

“Many UT activists in the project didn’t describe themselves with the word ‘feminism,’ which they identified with older women in NOW. They used ‘women’s liberation,’” says Green.

![Women protest in support of the Equal Rights Amendment at the Texas Capitol, April 1975. [Center] Martha Cotera holds “Liberty, Justice, All” sign.](https://lifeandletters.la.utexas.edu/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/JusticeforAll-1024x654.jpg)

“The term ‘feminist’ can hinder our understanding of women’s activities in the past because women who were very outspoken, very active, who seemed to be breaking norms at the time, were not always acting on behalf of all women,” says Jones, whose recent book, Goddess of Anarchy, delves deep into the formidable life of Lucy Parsons, a quintessential agitator of the late 19th and early 20th century who spoke of growing inequality and the rights of workers who were being displaced by machines, but was most certainly not a “feminist.”

“She was not sympathetic to women reformers. She really felt that they were just kind of tinkering with the capitalist system and that it needed to be destroyed,” Jones says. “It would have been unusual to find women, especially in the 19th and well into the 20th century, who had a view of universal womanhood; most women defined their place in the society within the context of their own kin, religious, class, ethnic, racial or regional group, and not exclusively according to their gender. Of course, to a certain extent that is the case today as well.”

Universal Womanhood

In fact, NOW, which was first headed by Betty Friedan — who is often credited for sparking the so-called second wave with her groundbreaking 1963 book The Feminine Mystique — has been criticized for operating under the ideas of “white feminism.” Rather than rallying behind the more radical views of women’s liberation, local and national groups of older, more privileged women seemed to prioritize political power.

“In Texas, when Anglo women decided not to give minority women equal status within the National Women’s Political Caucus — when minority women were over a big majority of the feminist movement throughout the nation — then I knew it wasn’t going to last,” Cotera says disappointedly. “They marginalized radical women, they marginalized minority women and they focused on power over everything. When you’re focused on that, you don’t last. You don’t build institutions.”

Things began to fall apart on the national level as women of color challenged the idea that white, heterosexual women represented universal womanhood.

“It’s a deeper shade of feminism. My culture is the lens through which I see feminism.”

Lisa B. Thompson

“If Betty Friedan says, ‘Let’s all go leave our homes and work,’ that’s great, but who’s going to take care of Betty Friedan’s children?” That question is posed by Lisa B. Thompson, a UT Austin associate professor of African and African diaspora studies and women’s and gender studies. She points out the reality of white, middle-class, married women going out and bringing “another white income into the home while paying a woman of color to take care of their kids and clean their house,” adding that the lowest-paid women are those working in child care.

“How does your feminism take into account those differences?” she asks. “That’s something we have to change — those who have the blow horn need to use it to amplify the issues of minority of underrepresented women and girls.”

Even before the women’s liberation movement, the suffragists faced their own battles along sectarian lines.

“When people see these images of white women in their white Victorian dresses with their lavender sashes in front of the White House, they get the idea that the suffrage movement was a white women’s movement,” Green says. “But black women were suffragists too.”

Green offers an example of the first big suffrage march on Washington, D.C., in 1913 when organizers decided to appease southern white women by directing black women to march in the back. But Ida B. Wells, a crusader against lynching at the time, wouldn’t have it and ultimately stepped in line with the Illinois contingent during the march, Green says. Others joined in.

“Every movement has its contradictions,” Green explains. “There’s not a movement where suddenly you’ve reached the pinnacle and everything is important. There’s always this working out of history and clashing ideas even within movements.”

Hines recalls debates within their campus groups about race and class and whether a person of color should be aligned with the black liberation struggle or the women’s liberation struggle, admitting that much of the national movement centered on organized groups of white women.

“We didn’t really have that term of “white privilege” or perspective of looking at what we take for granted, or what is so engrained in how things work, or the myriad of experiences, of steps ahead, or advantages you have as a white person in our society,” Hines says. White privilege wasn’t defined until the 1980s when people began to understand and define the inner workings of systemic oppression.

Coming Together

In 1989, Kimbrelé Crenshaw, a law professor at Columbia University and the University of California, Los Angeles, introduced her theory of intersectionality.

“If a black woman was being discriminated against, the law was asking her, ‘Were you being discriminated against as a black person or as a woman?’ It’s both,” Thompson says. “Intersectionality is taking into account my race, my gender, my class, my sexuality.”

The theory built on the idea of being a “womanist,” a term introduced by Alice Walker in her book, In Search of Our Mothers’ Garden. Walker writes: “Womanist is to feminist as purple is to lavender.”

“It’s a deeper shade of feminism. My culture is the lens through which I see feminism,” Thompson says. “And another way black feminists are intervening is by pushing others to ask themselves, ‘What are your concerns as a mother?’”

Black activist pioneers such as Mary Church Terrell and Ida B. Wells — who were involved with anti-lynching campaigns — were fighting a women’s issue, she explains. “Some people will say lynching is a race issue, but if you’re a mother, and you’re giving birth to someone who is going to be lynched, it’s a woman’s issue.” That is why it is important for women activists today to rally behind the Black Lives Matter movement and work to end police brutality, adds Thompson.

“Police brutality toward both men and women is an issue that runs through a lot of 20th century American history, particularly when there was so much movement from rural areas into the cities,” Green says. “It became an important part of history that angered black communities and affected mainstream politics.”

She says today it is important to ask what’s new and what’s not new. “The violence isn’t new, but having a national movement and a reaction to a national movement — that is new.”

“They marginalized radical women, they marginalized minority women and they focused on power over everything.”

Martha Cotera

In organizing the 2017 Women’s March on Washington after the election of President Donald Trump, people feared history might repeat itself and upper-middle-class white women would again hold the reigns. “Same old, same old,” some criticized.

“Ultimately, the people organizing it recognized it was so important for people to come together. And the march changed,” Green says. Protecting civil rights and taking a stand to end violence were two of the eight unity principles outlined by the women’s march committee, which was made up of African Americans, Latinas, Muslims and whites.

The march became the largest single-day protest in U.S. history, with more than 4 million people participating in 653 marches across the country. It was followed later in the year by the unprecedented and viral #MeToo movement, a cry echoed by millions in 85 countries to end sexual harassment and violence.

Agents of Change

Although the numbers are impressive, it still doesn’t paint a true picture of womanhood in the U.S., Thompson says, pointing out that black women voted for Hillary Clinton at 92 percent, while more than half of white female voters voted for Trump.

“A friend of mine created T-shirts that say, ‘Vote like a black woman’ because she believes that black women are the only ones consistently voting in the best interests of the country,” Thompson says. “Who’s supporting progressive causes? Black women are. White women need to have a conversation across their own community — talk to their parents, aunts, uncles, cousins, nephews and nieces — that is what is going to make the biggest difference. That’s the real hard labor. It’s easy to march at the rally with a sign and wearing a pussy hat.”

Movements are about values, most of which are instilled in people by their families, their homes and their schools. Activism is a natural progression that stems from that, Cotera says.

“When I was in school, we actually had civics classes. I was taught that if you are in a political space, then you have to respect that space and be the best you could be — in other words, citizenship,” Cotera says. “They’re not teaching that anymore. I don’t know if it’s a plan to develop uninterested and uninvolved citizens or what, but I was raised to be extremely aware of your responsibilities as a citizen, and I just don’t see that anymore.”

Like schools, youth organizations such as the Girl Scouts, Boy Scouts, Campfire Girls, 4H and the Y organizations also fostered good citizenship, but involvement in those organizations is on the decline, says UT Austin anthropologist and women’s and gender studies professor Pauline Strong.

“One way of creating change is to develop young people to think of new possibilities and think of themselves as having the ability to create new possibilities,” says Strong, who is also the director of UT’s Humanities Institute. “So, in between these organizations and changes in the future are the young people who are being socialized as agents of change.”

Since the 1960s, the Girl Scouts, in particular, put a strong emphasis on developing female leaders. “They really do train young people to gradually take leadership roles themselves. So, there’s a lot of planning things by the youth themselves, and I think that’s a really good model,” she says.

“We became addicted to the concept that we could change things, and when you inject that into people, it’s magical and buoyant.”

Alice Embree

But Strong worries that this model is hard to come across outside of these organizations, suggesting that there’s much more — and perhaps too much — play structured by adults and that many youth leadership roles have the character of “a sort of play-acting thing.”

“It has to be real,” Strong says. “There have to be roles for young people to really make decisions. They have to have the opportunity to make a mistake.”

Strong believes youth organizations are well equipped to address some of today’s most pressing issues: “Youth organizations do try to get kids into challenging environments outside. They try to introduce kids to those who are different than themselves and provide strong role models, who are both adults and older youth.”

Most importantly, these organizations provide young people with a community within which they can learn, grow and create change together. And if history has taught us anything, it’s that young people can be the most important agents for change.

Just as Cotera, Embree and Hines came into activism through the injustices they had witnessed in the world around them, so too will future generations.

“We became addicted to the concept that we could change things, and when you inject that into people, it’s magical and buoyant,” Embree says. “Coming together with people can be transformational, and I think that what we’re seeing today will work its way through changing this country.”

Recommended Reading:

Goddess of Anarchy: The Life and Times of Lucy Parsons, American Radical

Basic Books, Dec. 2017

By Jacqueline Jones, chair and professor, Department of History

Celebrating the Rag: Austin’s Iconic Underground Newspaper

New Journalism Project, Oct. 2016

By Alice Embree, alumna, Department of Anthropology (’82); Thorne Dreyer and Richard Croxdale

The Chicana Feminist

Information Systems Development, June 1977

By Martha P. Cotera

Beyond the Black Lady: Sexuality and the New African American Middle Class

University of Illinois Press, Aug. 2009

By Lisa B. Thompson, associate professor, Department of African and African Diaspora Studies