Researchers explore the role of religion in mobilizing African-American voters

The Sunday morning worship at Red Memorial* progresses like many services in African-American churches. Parishioners sing classic hymns, clapping and swaying along to the music. The pastor, the Rev. Red, greets the congregation the same way she does each week. However, there’s something different about the service, explains Eric McDaniel, assistant professor of government who studies the politics of faith and race.

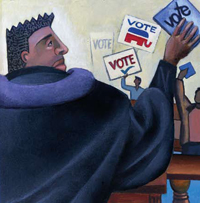

Along with a spiritually uplifting sermon, the Rev. Red delivers a less-than-otherworldly message to the congregation. Tuesday is election day and she emphasizes the importance of voting with an African-American church ritual, the call-and-response, to mobilize the congregation for democratic participation:

The Rev. Red: “Everybody…”

Congregation: “Vote!”

The Rev. Red: “And vote right.”

Congregation: “Vote right!”

At the end of the service, members pick up the church’s Sunday bulletin in which one page contains a single word: “VOTE!”

The scene at Red Memorial is an example of the discussions about the presidential election that were happening in African-American churches throughout the United States, McDaniel says. He researched churches in Detroit and Austin for his book, “Politics in the Pews: The Political Mobilization of Black Churches” (University of Michigan Press, 2008).

Historians, sociologists and political scientists have documented and examined the impact of church-based political activism for years, but McDaniel says they’ve neglected to examine why churches become politically active in the first place.

That’s the question he poses in “Politics in the Pews,” which explores how and why black religious institutions answer the call of politics.

“The black church has a historical legacy of political activity, especially during high points of racial conflict in the United States,” McDaniel says. “during the civil rights movement, Martin Luther King Jr. was famous for his ability to eloquently communicate blacks’ religious duty to vote. There was a sense of your duty as a Christian to vote and to protect the interests of other African Americans.

“However, not all churches, including black churches, are politically active,” mcdaniel says. “I’ve found that black churches’ political activism can be best described as a process, rather than a condition. It is mitigated by both the congregation’s preferences and the level of activism of the church leadership.”

McDaniel argues a church will become politically active when four conditions are met:

The pastor is interested in involving a church in politics.

Members of the congregation are receptive to the idea of having a politically active church.

The church is not restricted from having a presence in political matters.

And the political climate necessitates and allows political action.